Chris Jones remembers well the meals he made for himself in the earliest days of his cooking career as a poor journeyman apprentice, long before he achieved any fame as a contestant on Top Chef: ramen soup with an egg on top, washed down with a can of Pabst Blue Ribbon. While the ramen and PBR still fit harmoniously with Jones's life today working for a San Francisco–based startup, the egg doesn't. As the director of culinary innovation at Hampton Creek Foods, Jones is one of about 70 employees working for a company whose mission is no less than abolishing chicken eggs from the American diet.

It's not a wholly original idea. An egg replacement derived from chia seeds and garbanzo beans exists, as does another created from potato and tapioca starch. But Hampton Creek Foods has arguably attracted the most attention. Since its founding almost three years ago, the company has sought to reinvent popular foods such as mayonnaise and cookie dough that require the gelling, binding and emulsifying properties of eggs. It does this by substituting proteins extracted from plants for chicken eggs. Co-founders Josh Balk and Josh Tetrick came to their plant-based egg solution after extensive trials extracting and analyzing the proteins of over 4,000 different plants worldwide. They found about a dozen plants—the Canadian yellow pea was the best of them—that mimicked egg emulsion, without any of the environmental effects of the caged-chicken industry—fecal matter, dust and ammonia, to name some—or any of the high costs associated with the free-range chicken business. Investors, among them Microsoft billionaire Bill Gates, have put $30 million into the startup so far, , and the company recently announced an additional $90 million in venture capital funding from investors including Marc Benioff of Salesforce and Eduardo Saverin, co-founder of Facebook. Hampton Creek's current line of products—Just Mayo, Just Cookies and Just Cookie Dough—can now be found in stores like Whole Foods and Wal-Mart.

"The deep, deep why behind everything we're doing is this recognition that the food that we feed ourselves today is explicitly shitty for our body and for the planet," says Tetrick, a 34-year-old Alabama native who worked in Africa for seven years, including a stint with the United Nations Development Programme in Kenya. "Food that is better for the body and the world—what if it's more delicious and more affordable?"

At the core of Hampton Creek's philosophy is the belief that the environmental footprint of global egg production—the land, water, and fossil fuels required—is unsustainable. It takes about 39 calories of energy to farm one calorie's worth of egg protein. And in 2007, 59 million tons of eggs were produced, according to the U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization, a number expected to dramatically increase by 2030. All that farming is rendering huge amounts of environmental damage: Excess nitrogen and phosphorous from chicken manure contaminate rivers, and ammonia ventilated from henhouses pollutes the soil.

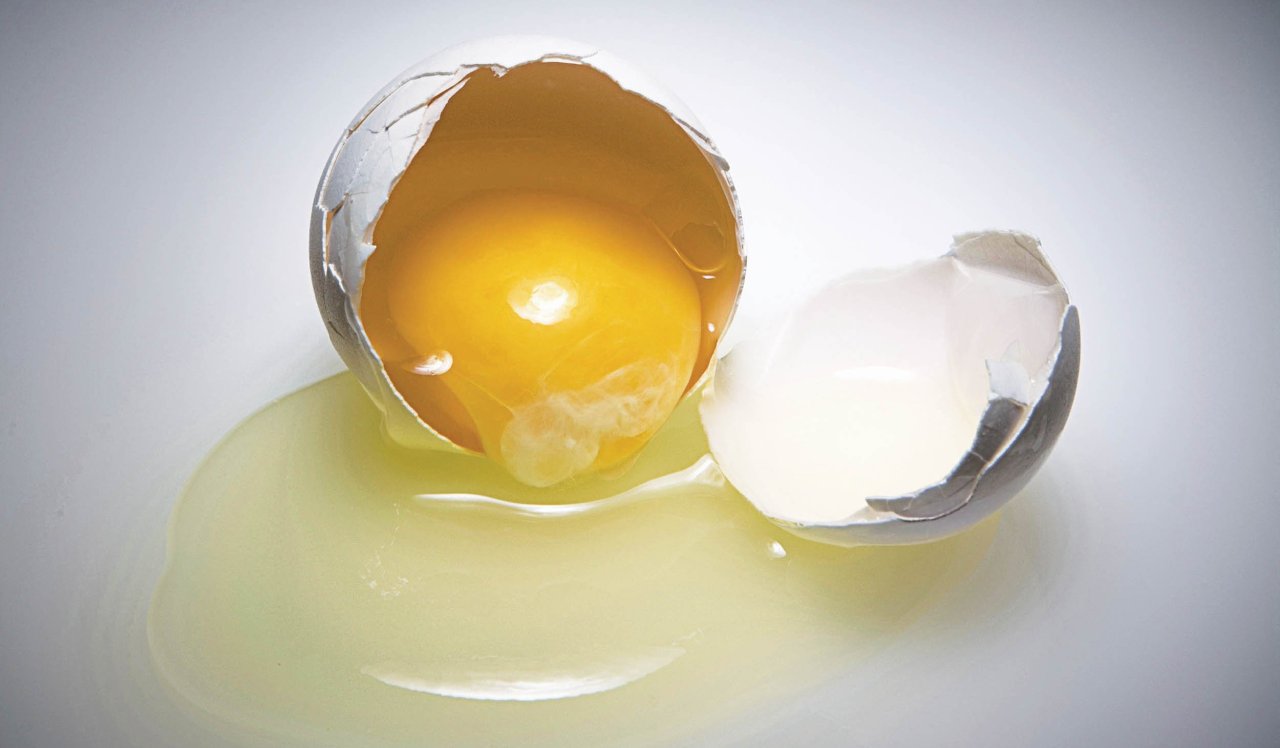

Eggs are clearly bad for the health of the planet. As for our health, disagreement abounds over any association between eating eggs and heart disease, but egg yolks are high in cholesterol and can lead to buildup of carotid plaque in the arteries, especially if you already have high cholesterol or other heart health risks.

Hampton Creek's products might be cholesterol-free and safe for those with egg allergies, but what Tetrick is really after is a reimagination of the entirety of food production. If Hampton Creek can figure out how to replace eggs with the proteins of plants that don't use much land or water, are relatively inexpensive and could be grown by farmers around the globe, it might figure out a way to better feed the world's catastrophically increasing population.

Leading this effort is an elite lineup of trained chefs. Along with Jones, who left the restaurant world in 2012 for his job at Hampton Creek, there's pastry chef Ben Roche and Trevor Niekowal, the startup's two research-and-development chefs. All three used to work together at Moto, the Chicago restaurant once routinely featured on the Discovery Channel show Future Food. (Roche was a co-host with Moto owner Homaro Cantu.) In a former time, the three chefs, who are all in their early 30s and have more than 50 years of restaurant experience among them, lived for the Saturday night dinner shift, when recipes and dishes they had perfected and prepared were given their final test: the plate of a hungry patron. Those days are gone, traded in for a 9-to-5 in which the goal is to create Just Scramble, a liquid scrambled egg made wholly from plant proteins and set for release in 2015.

The greatest moments of discovery for these chefs are often bittersweet; their optimism surrounding a startup poised to disrupt your morning plate of over-easy eggs wears thin when they realize how removed they are from your breakfast experience. "As a chef, a lot of things are instant gratification," Jones says. "If you have a great service or a bad service, you know right away. In the lab, you're working on a formula months on out, and you have to take the victories as they come."

The present version of uncooked Just Scramble looks as if a person took an egg and whisked it up with a fork—a big victory, according to Roche, who says that at one point it had the viscosity of pancake batter. Now it's more watery and cooks almost instantly when dropped into a sizzling skillet, just as a chicken egg would. "It's definitely heading in a positive direction," says Roche. "It cooks up more like an egg. It looks like an egg. It has a very similar mouth-feel to an egg."

The experimentation goes down inside the spacious, garage-like kitchen-laboratory-office of Hampton Creek Foods, where Jones and his cooking compatriots are huddled over stoves and pans and seated beside bioengineers, food scientists and data analysts. "We're that intuitive tool that these scientists need," says Jones. "A lot of the times we're answering the question 'What works?' as opposed to why it works."

Indeed, while the bioengineers and food and data scientists are busy picking apart plants—the goal is to create a database of the more than 400,000 plants known to man for their potential applicability in food—analyzing proteins, and determining which have certain properties more amenable to coagulation or emulsion, Hampton Creek's chefs have the grand task of figuring out how all of Hampton Creek's food products are functional and flavorful. In other words, they are responsible for figuring out if they've got a product your grandmother would put in her kitchen cabinet.

"I don't like when people think these innovative new food companies are making science-food or growing weird things in test tubes," Roche says. "We're making real food."

Hampton Creek's opponents beg to differ. Unilever, the $60 billion multinational food corporation behind Hellmann's mayonnaise, had filed a lawsuit against Hampton Creek Foods in U.S. federal court for, Unilever claimed, falsely advertising Just Mayo—whose label features an egg shooting up from a plant stalk—as, well, mayo. Unilever eventually dropped the suit, "so that Hampton Creek can address its label directly with industry groups and appropriate regulatory authorities," said Mike Faherty, vice president for foods of Unilever North America, in a statement.

Hampton Creek's efforts to replace eggs pit the company against a very powerful industry. They've already started to see some pushback: Late last year, for example, Buzzfeed reported that, in an effort to steer consumers away from egg replacements, the American Egg Board—a large egg marketing organization whose members are all egg producers—was purchasing advertisements that ran whenever someone performed a Google search for Hampton Creek products.

But Hampton Creek is focusing on the frying pan test at hand instead of possible courtroom battles. "People cook eggs thousands of different ways with different fats in the pans, with different heats, with different pans, with different style stoves," Niekowal says. "The true test is when we can have 50 people walk through and cook our egg off and it turns out perfectly."

It's a tall order. An egg produced from plant proteins might gel, but if the gel doesn't hold any water once it's in the pan, the egg will evaporate the instant it touches the pan's hot oils. Discovering complementary foods that react well with plant proteins to drive and mimic egg emulsion—something Jones, Roche and Niekowal are tight-lipped about—took six months. Niekowal recalls being overwhelmed leaving his post at Portland, Oregon's Le Pigeon restaurant—a two-time James Beard Award recipient—taking his first step into Hampton Creek Foods, and being told to create an egg from a plant.

"Here you might have two weeks where you're not hitting very well. Things are just not going well. Your experiments aren't turning out the right way," says Niekowal. "But you're also not just serving 100 people. Instead of touching 120 people a night who are paying upward of $200 a head, we can do this for millions of people every single day of our lives."