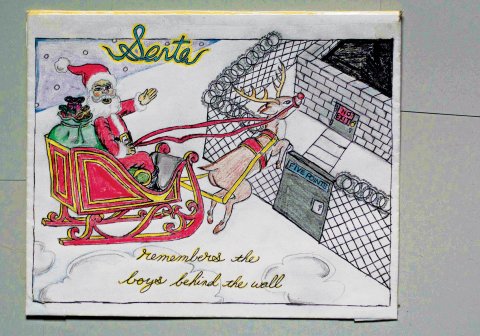

I wish I could have seen my wife's face when she opened the Christmas card I sent her in 2010. The previous year she had gotten my ponytail, and I knew I had to up the ante the following holiday, so I bought a card made by the local maestro. The cover depicted Santa Claus and his reindeer sleigh floating over the walls of a prison to bring inmates gifts. Opening it revealed the outcome: Some prisoners were plundering his bag of presents, while others were assaulting the mythical figure adored by greedy children. Sexually.

I didn't witness her reaction to this desecration of Christmas because I was in prison. Despite considering myself generally nice, in 2003 I had done something unequivocally naughty. We had married only a few months before my arrest and kept the relationship alive until my release from prison in February of this year. The U.S. Postal Service played a large part in its survival. After the thousands I spent in postage while inside for 10 years, I never planned to mail another card. However, there is no other way to send season's greetings to friends still incarcerated, so I am still licking envelopes, but knowing the cards I send will seem wimpy compared with those made by convict artisans; Hallmark lacks anatomically correct depictions of Class A felonies in its stock of yuletide imagery.

Prisoners send out a lot of letters and gifts; I had never heard of Columbus Day cards before my sentence, but guilt-ridden felons grab any opportunity to remind a wife that she has a husband, and a child that he is her father. These artifacts are churned out by entrepreneurs for an eager, and completely captive, market. Christmas season turns every joint into a bustling hive of gift making and card drawing.

Not all the cards exchanged require stamps. There are plenty of convicts doing their time "hard"—no phone calls, no visits, no mail. Some burned their bridges, others never had any. But prisoners have a way of playing family for each other. Forgotten men, remembered only by their parole board every two years, with no money and little hope of receiving even coal in their stocking, are sometimes cheered by their fellow cons. The cards rarely display much taste or craft, but they are proof that even the worst of men can be good sometimes. I sometimes made a card for a prisoner whose family had long forgotten him, and we both felt like men and not numbers. Receiving was good as well—the gifts I got from prisoners were markers of respect and friendship. I have kept every misspelled and childishly scrawled card given to me inside. The behemoth of a card that I got when I turned 30 was signed by 200 prisoners. They also spent too much of their money on pizza to hand out in my name; the organizer had robbed thousands of senior citizens in a Ponzi scheme, but spent a (jailhouse) fortune on me.

Presents can mean so many things. My grandfather was anonymously gifted a bar of soap by his co-workers at his first job after immigrating to America. He had followed the Soviet custom of taking a weekly bath, so the gift was a suggestion that he change habits. It humiliated the old engineer greatly, but in prison, where everything is twice as extreme, gifts could be mortal insults. Cheese might be the worst, as it identifies the receiver as a rat. But a candy bar left on a bed can be bad too. It's an invitation to a homosexual dalliance.

Transactions without compensation were not too common in prison. Nevertheless, the rule on unauthorized exchange forbade giving along with buying and selling. Presents from our keepers were infrequent. On the rare occasion that the authorities made a gesture, every convict in the prison I was in that year received a box of six green muffins two weeks after St. Patrick's Day. I was one of 2,500 men sickened by those muffins, but I will also never forget a cop who gave me few pounds of raw venison he had hunted, in gratitude for keeping my mouth shut about some tools he "borrowed."

The new world I had entered had rules and rituals that most of the men took for granted as being common knowledge but put me on a steep curve of learning crooked ways. Literature often helped me make sense of things; the memoir of my incarceration that I am writing for Penguin is titled 1,046 for the number of books I read while locked up. One of them was Dostoyevsky's The House of the Dead, an account of his imprisonment in Russia long ago. In one of Greenhaven Correctional Facility's cells, I experienced a moment of cognitive resonance: While I was reading about the protagonist describing a jailhouse artisan carving a chess set to sell to him in a Siberian labor camp, an inmate in the neighboring cell of mine was molding paper, ink and spit into a set to sell me.

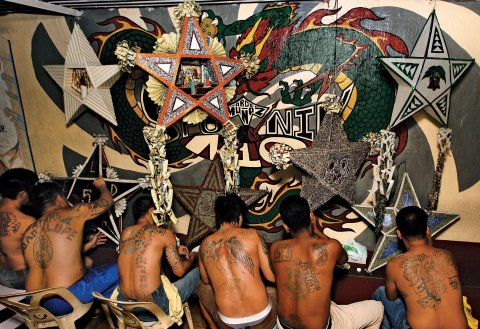

There are many fields of operation for prison craftsmen. Soap carvers do busts, garishly painted. Popsicle sticks are ordered by the case, and miniature cars, homes and motorcycles are glued into shape. Leather workers make purses, bracelets, belts and book covers. Those with a sharp "pen game" write poetry for others, and surprisingly intricate objets d'art can be crafted out of shiny potato chip bags and soda cans. The portraitists use ink, coal or oil. In an odd tradition of unclear origin, men braid their ponytails tightly, cut them off and send the hair home. My wife used mine to dust.

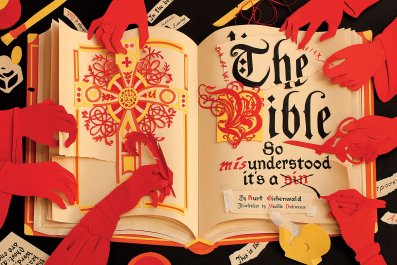

Shocking Pop-Ups

The most common product in the prison gift economy is the card. It can be mailed cheaply and personalized easily. Crafting individualized cards is the top of the trade: elaborate, folder-sized creations employing string, glitter, painted bits of dried pasta, photographic insets and psychedelic calligraphy. Pop-up features excite children, and pornographic depictions are for wives. They sell for as much as two packs of cigarettes. (Three packs is the rate for oral sex; one box of Newports—always Newports—is enough to get 30 milligrams of morphine.)

Over the years, I bought presents for my wife, mostly of a whimsical nature. I purchased a card drawn by an illiterate artisan, Meatball, of New York's Staten Island, who sported a swastika on one earlobe and SS bolts on the other. He could draw but not write, and made a card that the intended buyer refused because it was addressed "to my baby grill." I snapped it up, as well as a drawing of Adolf Hitler shirtless and brimming with muscles. In turn, she spent $50 on a weightlifting belt made for me by a murderer named Mafia. Once his sister got the money through Western Union, Mafia inscribed the double-headed Imperial Romanov eagle into it and painted it. I used it for years, and it hangs on my wall to this day. Unfortunately, Mafia's sister never forwarded the money to him, but that wasn't my problem.

Suicide rates notoriously go up every Christmas. For two years I worked in a unit for the mentally ill, and was told to watch the men for signs of suicidal intentions. The regular population was at risk too; Christmas guilt is common. But it keeps the craftsmen busy. Convicts in competition for limited resources are usually wary of each other, but they suspend hostilities for the holidays. Tough guys see nothing odd about giving cards to each other. The picture of macho men, some covered in muscles, others in tattoos, and all followed by long criminal records, exchanging Christmas cards seems unlikely, but I witnessed it every Christmas. Friends who had murdered and robbed the innocent wrapped gifts for their friends, hugged and joked about the absence of mistletoe. I never really fit in until I experienced this unexpected warmth on a birthday. A friend of mine crammed a contraband candle into a cupcake, lit it illegally in a clinic waiting room and sang "Happy Birthday" for me. It was the first time I hadn't felt out of place in years.

Prison friendships have the potential to be as deep and intense as the relationships between veterans of war. The cops' boots that we lived under rankled, but also unified us. It's no accident that inmates call each other "brother." They may rob in the street, but they hug in the joint.

When I robbed people myself to pay for my heroin addiction, I rationalized away my guilt with moral relativism. Reading Nietzsche when I was too young to understand his context convinced me that there was no good and evil, right and wrong. Today I know this is not true, and this revelation came to me while I was serving my sentence. In prison, I encountered genuine evil, which is no Christmas story. But I also saw good. Over 10 Decembers, I witnessed many Christmas cards exchanged by convicted felons. I had my birthday celebrated with a contraband candle (they are banned because one can make key impressions in wax) and song. This friend had killed twice; after murdering his girlfriend and doing 15 years for it, he stabbed his best friend and got 25. Death in prison was inevitable for him and he had taken two lives, but he risked solitary confinement and mockery to make my birthday special. Nietzsche was wrong to preach that good and evil are man-made concepts. Inexperienced in life, he just never got a card from a double murderer.

Convicts would like their families to forgive their absence and accept a substitute: a Christmas card with a pop-up Disney character or reproductive organ. It's often wishful thinking but keeps the artisans and local post offices in business. As a child, I awaited Christmas gifts with greed; as a youth I gave them strategically. In prison I saw the desperation with which gifts are sent, as well as more ominous reasons for giving them. Getting cheese is bad; finding a candy bar on your pillow might be worse.

But when I took those classes on identifying the signs of suicidal intentions, I learned about the worst gift of all. When a prisoner gives all of his possessions away, it's because he won't need them where he's going. A friendly patient in the unit for mentally ill prisoners I worked in presented me with all of his tapes and books; I accepted none of it and alerted the counselor immediately. When they stopped him he had already set up a noose. And Christmas was only a few days away.