This Thanksgiving I will enjoy a roasted turkey surrounded by squabbling family members for the first time since 2002. I have a lot to be thankful for; for the past 11 Thanksgiving afternoons I had just a few minutes to eat slimy turkey roll off a plastic tray, rushed along by guards eager to get home for their holiday meal. Thanksgiving in prison was a meal that implied I deserved no better.

I was arrested in November 2003 for five charges of armed robbery. I had graduated from New York University in 2000 and begun a career in publishing. But I also dabbled in drugs, and after two years of heroin addiction, I had a $100-a-day habit and owed my violent Ukrainian dealer five grand. Using the same pocketknife I once took camping as a boy, I turned to robbery. Luckily no one was hurt, and newspapers dubbed me "The Apologetic Bandit" for the contrition I expressed to my victims. Nevertheless, the judge gave me 12 years. I was released in February, and having paid dearly for my crimes, I finally have a turkey breast and feuding uncles in sight.

New York state calls its jails "correctional facilities." The goal of improving prisoners includes eventually returning them to society, but many convicts have never fit well in the conventional world to begin with. Some have not had the experiences a civilian takes for granted, whether it's fishing, summer jobs, going to high school, flying on airplanes or having parents. I learned the telltale signs of a group home youth in prison mess halls; the guys who wouldn't touch the vegetables had been raised without parents to teach them to eat greens. On Thanksgiving the clue was the stuffing. Men who had graduated from state care to prison never ate it. They didn't know what stuffing was and were not prepared to risk trying it. In their lives, most surprises had been bad news.

Without access to alcohol or the opposite sex, all celebration in jail is done through the alimentary canal. Four holidays are marked with special food: turkey on Thanksgiving, fried chicken on the Fourth of July, chicken breast on New Year's Eve and roast beef on Christmas. Lesser holidays like Columbus Day, Memorial Day and Labor Day call for two hamburgers and two hot dogs. Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday isn't on Albany's calendar, while St. Patrick's Day is commemorated with corned beef, despite not being a national holiday. (Policing has been an Irish business in this state for over a century.)

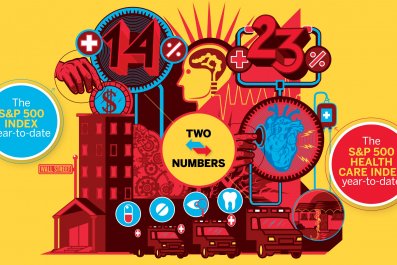

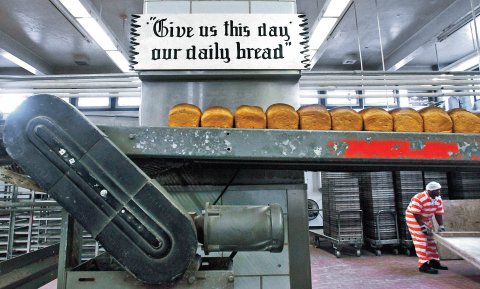

Introducing those from the margins of society to the shared national culture they've preyed on is a good reason to celebrate Thanksgiving in prison. But doling out turkey to the 57,000 prisoners is expensive; real meat in New York prisons was phased out 20 years ago, along with the higher education programs. For the most part, soy substitute satisfies the nutritional requirement for protein, although a weekly chicken leg survived the budget cuts. The Thanksgiving solution is to serve the cheapest substitute that can still pass for turkey.

The regular Thanksgiving dinner is three slices of turkey roll, a log of something white and speckled with the occasional beak or bone. There is also stuffing, cranberry jelly and carrots. The meal is early; by 5 o'clock, the prisoners are locked in their units by a skeleton crew. The rest of the staff is home celebrating. With a real turkey.

Holidays are approached with ambiguity in prison. The administration appears to encourage inmates to celebrate them; the staff resists. I once spent Christmas in the Special Housing Unit. It's a prison on the Canadian border composed entirely of solitary confinement cells. It was cold, the staff was mean, and it was as far from New York City and my family as it is possible to be while remaining in New York state. Not a very correctional setting. A local church had donated Snickers bars for the inmates, but they sat in cases for two weeks because the officers refused to hand them out. Finally the facility's imam made a special evening visit on Christmas Eve and walked around pushing the candy bars through the slots in the doors used to slide trays of food into cells. That facility holds about 2,400 inmates; working alone, it took the imam all night to hand out the gifts, while the guards read newspapers.

Segregated Mac and Cheese

Just as grass grows through cracks in the pavement, inmates celebrate despite their limitations. They are not consciously asserting themselves as human beings who deserve to participate in our society's holidays; they just know it's jailhouse tradition to cook big on Thanksgiving.

Prison culture is short on meaningful dates, although convicts in New York state memorialize September 13 by going to the mess hall but not eating the food. That's how they commemorate the Attica riots, which began on that day in 1971. Young prisoners are taught this and all other customs by older ones, and they also learn to save their food and money for Thanksgiving to make the biggest meal of the year.

After the trays of turkey roll are served at 4 in the afternoon, the prisoners return to their dormitories or cell blocks (depending on whether the prison is a medium- or a maximum-security facility), where the cooking has been going on since early morning. With only a few stoves and pans and microwaves available, every hour of the day is required, especially since three feasts are being prepared. There are three chefs and their assistants. Three long tables are set up in the common rooms, using every card table and cardboard box available, and homogenized in appearance with white sheets that serve as tablecloths. Plastic trash bags keep the flies off the food. There will be three batches of mac and cheese, three pitchers of Kool-Aid. The incarcerated population can be divided into three main groups; whites, blacks and Hispanics, and each of the three tables is for men of each race.

Since the state of race relations in prison is about where the nation was in 1948, whites, blacks and Hispanics eat separately. When the real enemy appears, as it did in Attica, the men unite, but in everyday life segregation remains the rule. The gravity of breaking bread with a man is understood with an almost biblical earnestness, so the races do not share food. Men usually live in trios of "cooking squads," so that the business of procurement, preparation and cleanup can be delegated. These teams are always uniracial; I was firmly told that if I cooked with an African-American or Hispanic, I could not return to the whites' table. However, on Thanksgiving, many rivalries are put aside to share specialties like the curry powder Jamaicans smuggle in or the Latinos' method of boiling an unopened can of condensed milk to make dulce de leche. There is also a friendly competition between the races to have the most elaborate meal. As bellies fill, the men soften, and often break the usual rules and racial barriers by sending samples from table to table.

The whites spend the most money by ordering smoked meats from a company specializing in selling hams and turkey breasts to inmates. The mail-order business was rumored to be run by correctional officers, and this was a reason given by many who would not order from them, but it was also very dear, so that probably deterred some customers as well. (Smallish, smoked turkey breasts were $40.) Latinos were deemed the finest cooks; they knew their way around the spices, though their devotion to garlic sometimes killed the vampires in our sealed dorms. The black table always had the most food. Within their community the dilemma was pork; approximately half the men were nominally Muslim, and good collards and okra require swine. Turkey bacon is an impotent compromise.

Prisoners with nothing to contribute buy a place at the table by doing the dishes, or just wait until the others finish for leftovers. No one goes without, and the rest of the week is devoted to polishing off leftovers; without access to refrigerators, the men eat quickly.

The Magic of Frozen Mayo

Prisoners are not wealthy; I lived on $100 a month and was in the 1 percent. These elaborate Thanksgiving meals bankrupt many inmates, but the men are willing to spend half a year's accumulated state pay on food for this day, only to give away much of it. It's not rational, but when has ritual ever been? Just as the state makes its point with disgusting and dispiriting turkey logs, the prisoners make theirs with excess. The cost and waste of it shows that not only are the prisoners deserving of the holiday but they can handle it on their own quite well.

Prisoners in today's system of "corrections" and turkey beaks struggle for their very identities, and Thanksgiving is a battle in a larger war. Waste demonstrates strength, wealth and status in the neolithic society of the incarcerated. Despite being reduced to numbers, the prisoners do not settle for turkey roll. The makeshift buffet table groaning with a giant's feast is the defiant answer to flimsy official meals. The guards get the message too.

Being locked away from family and friends hurts a little more on holidays. Hardened convicts can still be susceptible to the pain of loss; an acquaintance of mine once went out to the row of phones in the yard to call his wife, learned that she had left him and hung himself 10 minutes later. While prisoners generally mistrust and plot against one another, every Thanksgiving I saw the men play family for each other. Singing songs, telling tales and making lots of gratuitous physical contact, along with simply feeding one another, was the best they could do.

And that food was uniformly excellent. Using the meager resources of the commissary, packages from home and warehouse theft, prison cuisine is a reminder of the native ingenuity that made man king of the planet. The limitations make it all more interesting. Many joints don't allow cooking oil because of the terrible damage it can cause if boiled and thrown in a face. But who doesn't crave some greasy fried food now and again? Mayonnaise is available in every commissary; freezing it on a window sill locks up the solids, releasing the oil so you can fry away. Where flour is not sold, soaking dry ziti for a day makes dough. Carefully microwaving sausage casings results in pork rinds.

On Thanksgiving the tables are laden with macaroni and cheese, baked with Gruyère from someone's package from home and bread crumbs. Eggplant slices are fried and then baked into parmigiana. Hams are cooked with pineapple, and endless bowls of fried chicken line the tables. The most traditional of prison dishes, at least in New York state, is jack-mack: canned mackerel in brine. A pound of it costs 79 cents. There are innards and slimy skin to dispose of, but you can batter and fry the two-bite fish fillets. Jack-mack may be a standard of convict cooking, but the cheesecakes compete with those made by professionals with stoves, virgin oils and reputations. In prison, I ate amazing versions with coffee swirls or caramel and sea salt toppings. The meals close with these luscious desserts, and then the inmates head to the toilet stalls to smoke.

The Unbreakable Bread

Prison Thanksgiving is nontraditional because of the unorthodox foods prepared, but it also harks back to the older tradition of making do. By sharing food, even between the segregated tables, convicts embody holiday's spirit. Especially since they also share checkered pasts with this continent's first big wave of migrants. America was not exactly settled by the straight and narrow. Those Pilgrims, who also had severely limited resources, treated the Native Americans who assisted them horrifically. The incarcerated Native Americans whom I met did not celebrate the holiday at all for this reason. However, Native American custom is also resurrected in the potlatch-like display of ceremonial excess: way too much food. They deserve Thanksgiving, and they're going to have one, and it's going to be big.

And why not? The convicts of America are a thankful lot. Most are getting out eventually, and conditions in U.S. prisons are not nearly as bad as they've been in the past and are currently in other countries. More important, the United States is the land of second acts; another chance is possible. And for some inmates, there is the loving family that visits and brings that Gruyère for the macaroni and cheese.

Incarcerated men like Thanksgiving and bake great cheesecakes in microwaves to show it. So great that sometimes the guards forget another of the many unwritten rules and have a slice. As the collards travel from the black table to the Hispanic one while the Latin bacalaítos make it to the white guys, who have sent around kielbasa by then, walls crumble and the bars are momentarily forgotten. And when a slice of cheesecake discreetly lands on a guard's desk, the most unbreakable bread of all is crumbled, at least for one night.