The ice caps are melting, the Middle East is ablaze, Ebola stalks Africa and the economy is wobbling. What better time for an International Stoic Week with co-ordinated events across the globe and net, and a free online guide to Living the Stoical Life?

For such cold comfort we can thank the Stoicism Today (ST) organisation, based at Exeter University, in southwest England. On its website, there's a handbook to download, and an audio guide. There are contributions from celebrities and sages, tweets and chat-rooms and blogs. Under its auspices, there's even a programme in British schools for the duration. Well, in uncertain times, don't we all need to stiffen our lips?

Yes and no. Named after the Athenian porch, or stoa, where Zeno founded its first school in the 3rd century BC, developed over 500 years by thinkers like Epictetus, Seneca and the wise Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Stoicism is an admirable response to life's challenges. But what we often mean by it – a sort of grim repression – only scratches the surface of a rich seam.

A key concept of classical Stoicism is using the mind to control harmful emotions that leave us discontented, inadequate and anxious; and given that common ground with the theory of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), the philosophy is now attracting increasing interest from psychologists. You could almost say Zeno invented CBT.

And life coaching. The foundation of Stoicism is the pursuit of virtue, to be cultivated in oneself and radiated in the wider world. Virtue, a sense of proportion, self-improvement and restraint – all achieved with the help of meditation and reflection – are then rewarded with peace of mind, and that's the only prize worth winning.

Just ask the world's coolest Stoic, professor Massimo Pigliucci, 50, an ear-ringed Italian philosopher based at the City University of New York. In an experiment on himself, he's been living by the Aurelian code for the last two months and intends to continue for another ten.

He meditates on his behaviour several times a day, reflects on Stoical aphorisms over breakfast and diarises his progress before bed. He tries to be less judgmental, "because Stoics feel sorry for people who are ignorant", and becoming more mindful in everything he does – "which means engaging, unlike the Buddhist version which means the opposite".

Pigliucci gives two small examples of the theory in practice. At the gym, he's now leaving his iPod in a locker and concentrating on his exercises, "with the result that I feel much better for them". And mindful of others, he's started limiting his smartphone use, which – while honing his self-restraint and returning some control over his life – improves his and their social interactions.

You see, Stoicism really isn't about detachment. Some of its tenets were hugely influential on such later belief-systems as Christianity and the Twelve Step movement, and would seem rather obvious today if repeated in self-help books. But too often we overlook the obvious. That's why one aim of the ST team – comprising three psychologists and four thinkers – is to learn more about using the philosophy in the clinical treatment of mental problems.

So, let's say you feared a daunting prospect. Both the CB therapist and the Stoic would point out it hadn't happened yet. They would question its likelihood and, since there are greater forces in the world than our puny wills, ask if could it be averted. If not, why worry? The only things we can master are our thoughts, but they can control our emotions. So by getting things in proportion, we can be content. Besides, what doesn't kill us makes us stronger . . .

You get the picture. And while Stoics do not believe in an intercessory god, their spirit suffuses the Serenity Prayer, written by theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and later hijacked by the Twelve Step movement.

That, however, is but one of many 'spiritual' loans. The equality of the sexes – even of slaves and freemen – are Stoic concepts; as is the need to love and nurture all creation. Which is all very well. But in a results-driven world, a single question matters: does it work? Does living the stoical life produce a measurable increase in one's sense of wellbeing?

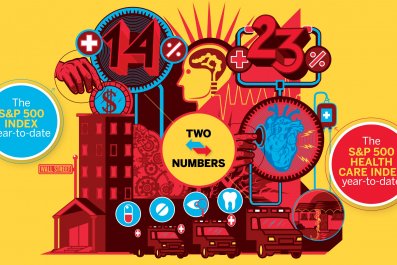

Finding a definitive answer is another of ST's missions. At either end of its week-long programme, you're invited to complete an attitudinal questionnaire; and if the analysis of last year's results is any guide to this year's, even a Stoic might permit himself a smile.

In 2013, around 2,400 participants reported a 14% improvement in life satisfaction, with a 9% increase in positive and 11% decrease in negative emotions. As for virtue, 56% gave themselves a mark of 80% or more when asked whether the course had made them better and wiser people.

QED, then? British media-philosopher Jules Evans would say so. The Saracens rugby team is one of his clients. (They need to accept referees' decisions and missing the cut.) And in one tradition that stretches "from Boethius in a 6th century jail to James Stockdale in a Vietnamese POW camp", he's seen the benefits bestowed by a course he ran for inmates at Low Moss Prison, in Scotland.

Meanwhile, psychosocial rehabilitation worker Ian Guthrie reports successfully exploring the teachings of Marcus Aurelius with his clients, all of whom are classified as seriously and persistently mentally ill (SPMI). Since February, he's been facilitating small weekly group sessions at a clinic in Kansas, Missouri, and reports that "Stoic self-regulation is one area of clinical value that has gained particular traction".

"It underlies contemporary theory on rational emotive behavioural therapy (REBT)," he says. "For example, I encouraged a client with paranoid delusions to follow Stoic principles, think rationally about his emotions and perceptions, and embrace what he knew to be empirically true – and he reports greater success in maintaining his grasp on reality."

Naturally, for the moment, other Stoics are curbing their enthusiasm. The ST website warns its survey is unsuitable "for anyone suffering from psychosis, personality disorder, clinical depression, PTSD, or other severe mental health problems". Professor Pigliucci says the ancients would have only prescribed philosophy to those of "sound reasoning".

But whatever the ultimate truth may be, it is essential that we bear it stoically.