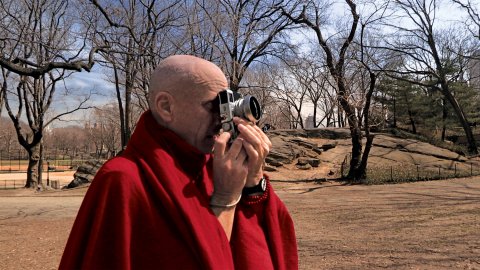

One good thing about being a Buddhist monk is that you never have a bad hair day. Not that you need to be a monk to shave your head. "Today people shave their heads and that becomes their look, but back then there were no shaved heads," recalls Nicky Vreeland. "Except Yul Brynner."

Vreeland has been a monk for 30 years now—he left New York in 1984 to join the Rato Monastery in the Tibetan Settlement of Mundgod in southern India, where he is now the abbot. His Holiness the Dalai Lama appointed Vreeland, making him the first Westerner to hold such a position in over 2,800 years. But before he donned the red robes, Vreeland was what one friend called "a very committed dandy."

"I was always taught to have a handkerchief in the pocket of my jacket," says Vreeland in Monk With a Camera, a new documentary about his arc from playboy of the Western world to monastic of the East. "My father taught me that; I'm sure his father taught him. Whether or not anyone saw it didn't matter."

For Nicholas Vreeland was to style born. His grandmother, Diana Vreeland, was the legendary editor of Vogue and his father, Frederick "Frecky" Vreeland was an American diplomat who raised his family in Switzerland (where Nicky was born), Germany, France, Italy and Morocco before returning to the U.S. when Nicky was 13. Footage of Nicky's parents cavorting at society events look like outtakes of a very louche party scene in Mad Men, the beautiful couple dancing into immortality.

Which might be why his parents' divorce hit him so hard. Nicky was at Groton at the time, and on his visits to New York City he began to spend more time at his mother's legendary jungle red Park Avenue apartment. "Everything in her life was cultivated to be the best," his brother Alexander says in the film. "Nicky absorbed everything."

"She was an idealist—chasing after fantasies, going beyond material boundaries, visited by visions of white churches and white horses and poppies on the verge of dying," Harold Koda, head of the Costume Institute at Manhattan's Metropolitan Museum of Art, told Vanity Fair in 1993. "I don't think it's a coincidence that her grandson Nicky became a Tibetan-Buddhist monk."

When you have an interest in photography and your grandmother is Diana Vreeland, you have an advantage over most aspiring shutterbugs. At the age of 15, Nicky became an apprentice to Irving Penn, with his grandmother's assistance. Such was growing up Vreeland: Looking through a collection of family photos, we see portraits by Richard Avedon and Cecil Beaton.

And young Nicky had an eye, one that seemed to look to the edges of the world he moved in. He took a series of portraits of bespoke tailors, the men who sewed the clothes that others were photographed in, and lived the carefree life of a privileged international kid. "Our parents were so absorbed in their own lives that Nicky and I were living alone in Paris, and Nicky was just partying," recalls Alexander. He chased girls and raced cars, often with diplomatic immunity.

Somewhere in his travels the fun fell out. After reading an article about meditation on a road trip through South America, Vreeland began to practice; by the time he returned to the States he was looking for a teacher. "Was I unhappy? No more unhappy than anyone else," he recalls in the film. "I had a belief that there was something beyond material satisfaction."

In 1977 John Avedon, the son of the photographer, introduced the young seeker to Khyongla Rato Rinpoche, founder of the Tibet Center in New York. Vreeland took to this apprenticeship as assiduously as he had photography, and, in 1979, on assignment in India, he met the Dalai Lama. In the world of Tibetan Buddhism, this is how you become a made guy.

Before he left for the Rato Monastery in 1984 (something the Dalai Lama had encouraged him to do), Vreeland had to renounce some more worldly goods. John Avedon recalls him putting all of his Italian shoes out on Avenue A; about the same time someone broke into his apartment and stole all his cameras, which he took as a sort of sign. "I think photography has for me a quality of addiction," says Vreeland, and his affinity (and talent) for it is something he grapples with in the film. "If you are taking photos with the hope of helping others, it is virtuous; if you just want to get rich or whatever, it is selfish." Alexander gave him a camera before he left and implored him to keep taking pictures.

For the next 14 years, Vreeland stayed largely within the walls of the monastery, studying Buddhism and getting to know his fellow monks. Most of them were from Chinese-occupied Tibet, where even mentioning the Dalai Lama can get you in trouble. Their reality was as foreign to him as his was to them; some did not believe that the world was round, and he recalls trying to explain time zones to them: "I'd say, 'If I were to call America it would be the morning before today,' and they'd say, 'Call America?' They couldn't even get to an appreciation of the time difference."

At times the isolation was vexing. "I received a letter from my mother's doctor telling me she was very ill and could live between two weeks and two months," he tells me by phone from New York, where he now spends about half his time. "It took one month for that letter to get to me. I had told her I would go and visit her before she died. I had no idea if she would be alive when I reached America." (She was, and there are images of him from that last trip, in his robes, pushing her in her wheelchair.)

In his time at the monastery Vreeland saw the population grow from a dozen to hundreds today. He started traveling to New York more frequently to help Khyongla Rinpoche with the Tibet Center, as an interest in Buddhism was growing in the U.S. "On my initial trips back I really felt uncomfortable walking around the streets of New York in monk's robes with a shaved head," Vreeland tells me, "but I began to feel more and more welcome. That was partly me feeling more secure as a monk, but our Western culture was also becoming more empathetic to Buddhism and the idea of the monk. I attribute that change to His Holiness the Dalai Lama." (Vreeland has written two books based on the Dalai Lama's teachings, An Open Heart and A Profound Mind.)

In 1999, Vreeland approached the city of New York to get permission for the Dalai Lama to give a speech in Central Park. "We were told yes, but we shouldn't expect too many people on a Sunday, maybe [10,000] to 20,000." The Parks Department estimated the turnout to be closer to 65,000. "And these were not Buddhists," says Vreeland. "These were people interested in hearing from a true practitioner about how to become a better person."

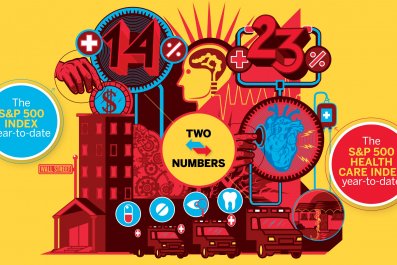

Meanwhile, back at the monastery, things were falling apart. The place was badly in need of renovation and expansion. Vreeland used his connections to help raise money, but in 2008, many of those pledges disappeared along with much of the world's money. He had continued to take photographs for much of his time there (it was a visit from Martine Franck, the widow of Henri Cartier-Bresson, that got him back into it), and Alexander suggested he start selling them to raise money. There were events in Paris, Berlin, Rome, Naples, Genoa, New Delhi, Mumbai and New York, which together raised $400,000—enough to finish the work.

"It's extraordinary that the photographs managed to pay for the construction of the monastery, sort of a miracle," Vreeland says. His earlier misgivings about taking photographs (the photos on view at his website include everything from market scenes to monastic rituals) were resolved when his art benefitted others. And as much as he enjoys being in both worlds and has struggled with the monastic life ("I'm very fond of women," he says simply), he has no thoughts of returning.

"Being of benefit to others does not require that you be a monk," he says. "[And] becoming a monk or a nun should never be a cop-out. It should never be removing yourself from the ultimate spiritual goal that is to be of benefit to others."