When 40-year-old Liberian civil servant Patrick Sawyer died of Ebola earlier this year in hospital in Lagos, having carried the disease from his home country to Nigeria, global health workers feared the epidemic would spread in West Africa's most populous city. But no one paid much attention to the victim of another epidemic further north. One day before Sawyer's death, on 24 July, the worried parents of a 16-month-old toddler in Kano state had discovered their child was suffering from the symptoms of a disease had supposedly been largely wiped out of existence – poliomyelitis.

Although the two viruses are very different, the efforts to tackle polio and Ebola have been intricately connected, largely through the efforts of the 30 year, multi-billion dollar, global polio eradication campaign that stands on the brink of wiping out polio – but that brink is precarious. If the teams involved succeed, global disease eradication will have a new blue-print. The consequences of not succeeding – after decades of painstaking work across the world – seem impossible to contemplate.

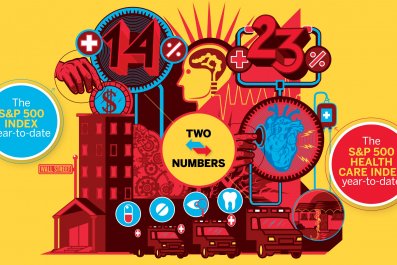

Polio has been almost entirely extinguished from the collective memory of anyone living in Europe or the US. It's taken $8.6bn (£5.5bn) to achieve 99% eradication of polio and it's going to cost an estimated further $4.5bn to tackle the remaining 1% of cases during the next four years.

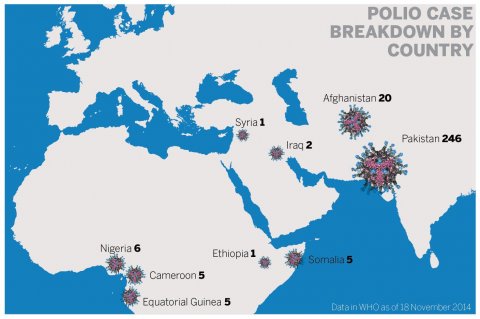

Earlier this month Dr Stephen Cochi of the CDC's Centre for Global Health announced a "major milestone" with the likely elimination of the second of the three strains of the wild polio virus (subject to a surveillance period of three years). But internationally, war and insecurity makes wiping out polio's tiny number of remaining cases frustratingly elusive. In March 2014, the World Health Organisation (WHO) admitted the scale of the problem, announcing: "The fight to eliminate polio is now imperiled . . . by insecurity, targeted attacks on health workers and/or a ban by local authorities on polio immunisation." The final stage of the fight against polio is hanging in the balance. Not only must workers target endemic areas of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria, where polio has never been wiped out – they must also access war zones in Syria, Somalia, Iraq and across the Horn of Africa where polio has returned in areas of conflict, making it impossible for vaccinators to work.

Those involved fear their work will simply have given satisfaction to critics of the long campaign who claim it has spent a bottomless pit of money and effort chasing an impossible dream – money and effort that could have been better spent on more achievable health efforts around the world.

No-one feels that pressure more keenly than doctor Faisal Shuaib. Despite the fact that Nigeria is officially Ebola-free as a direct result of his own work against polio, the death of another child from polio hits his team hard.

Faisal grew up in northern Nigeria and, after qualifying as a doctor, took up a position in public health for the WHO, becoming deputy incident manager at Nigeria's innovative polio Emergency Operations Centre (EOC). When Nigeria's first Ebola case was diagnosed, he was immediately transferred to head up an Ebola EOC.

For Shuaib, the polio diagnosis of 24 July was tough moment – the polio eradication campaign was within a whisper of a phenomenal breakthrough, but yet another child was paralysed after missing some of the repeated series of immunisations so important in tackling the virus in areas with poor sanitation. "I grew up seeing people crippled by polio along the sides of the road," Shuaib says, "Eradication is within reach and we are on the cusp of Africa being polio free – but the gains we have made are fragile and we must not let the fight to tackle Ebola set the clock back."

"The Ebola virus coming to Nigeria was something new, and its been tough," Shuaib says. "Working on the polio programme is very demanding, but having to manage an Ebola outbreak of this magnitude has meant living with the possibility that if you don't get it right it could have potentially overwhelmingly catastrophic consequences for the whole of West Africa. When you see your colleagues dying around you, it wears you down and saps all your faculties."

Nonetheless, by implementing the same techniques that have proved so successful against polio – setting up an EOC to ensure a fast and co-ordinated response and establishing rapid house to house surveillance system – Shuaib and his colleagues appear to have brought the Ebola epidemic under their control in Nigeria.

THE FINAL HURDLE

The Nigerian response to both Ebola and polio is tracked and coordinated with a series of global health agencies, including the Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, where a series of anodyne office buildings resemble a suburban office park rather than a high security complex that houses samples of the world's deadliest diseases.

A walk to the polio lab at the CDC can involve passing the building that houses the last surviving stock of smallpox, riding on the lift past the floor where there was recently a leak from the anthrax lab, and turning the corner by the rabies lab, to find a test tube filled with a clear liquid, spinning frantically, ready to reveal whether it contains a variant of the polio virus transported overnight from an outbreak in East Africa.

Only 60 years ago, poliomyelitis conjured even greater terror than Ebola does today – striking silently, and without warning, across the world. The fact that it no longer inspires such fear is due in large part to the work of scientists like Dr Cara Burns, who runs the polio lab at the CDC. Together with the scientists and tacticians at CDC, a dedicated team at the WHO, UNICEF, Rotary International, and the billionaire philanthropy of Bill Gates, polio has been wiped out from 99% of the world.

"We can't fail," says Larry Brilliant, an epidemiologist and President of the Skoll Global Threats Fund, who played a key role in the successful WHO smallpox eradication program – the only other disease to have been totally eradicated. Despite the polio campaign's breathtaking resources and technology (something it is reluctant to explain, as the campaign's use of satellite mapping can be highly controversial in parts of the world), Brilliant sees the same spirit of idealism and endeavour that characterised the effort to eradicate smallpox 40 years earlier. "We must eradicate polio. And if we don't it is not just this one disease and all of its human pain and suffering that's at stake – it's anything we might do in the future as a global health community."

It is a campaign that used unprecedented resources in the battle; namely the most advanced satellite technology in the world to help map communities and track volunteers, combined with the oldest forms of transport, including canoes and camels, to transport vaccines – and a large element of human persuasion needed to win over politicians, religious leaders and parents into accepting the countless rounds of oral doses needed to make the vaccine successful. Each child must receive at least eight rounds.

It is also a campaign that many people are willing to risk their lives for. Polio vaccinators have been targeted and killed by rebel groups in Pakistan, Nigeria and the Horn of Africa. Since 2012, more than 50 polio volunteers and workers were murdered – more than are estimated to have died of polio.

THE POLIO BUSTERS

The lure of playing a part in what could be the biggest leap forward in global health in the 21st century seems irresistible, yet the hundred or so called polio-busters – health workers from 34 countries around the world who have gathered at the CDC in Atlanta for three weeks of intensive training before voluntary placements in the field – find it impossible to fully explain why that's the case. Most will leave young families behind to undertake five months of unpaid placements delivering the polio vaccine. They know they are risking their lives.

Selamawit Satato, a quietly spoken 34-year-old nurse from the town of Soddo in Ethiopia, has recently volunteered to spend five months working as a polio volunteer in northern Nigeria where polio workers were targeted and killed in 2012, and where attacks by rebel groups like Boko Haram are a serious threat. "I feel I am in danger, she admits, "but I want to contribute to eradicating polio . . . and even if there is danger I have decided to go to Nigeria in order to put all my efforts into eradicating this disease."

Impossible idealism, intense commitment, immense difficulty, internecine political negotiations, and sometimes bitter rivalry, have been the hallmarks of polio eradication from the very beginning. Polio was an unseen terror that stalked the early-to-mid 20th century; killing some, paralysing many more and bringing to mind horrific images of lives saved, but horribly restricted, in iron lungs where patients sometimes spent years unable to even drink a sip of water for themselves. At its height, 8,000 children were paralysed every year in the UK. By the 50s, however, polio appeared to be a disease of the past, with two competing (and acrimoniously contested) rival vaccines – the injected inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) developed by Jonas Salk, and the live oral polio vaccine (OPV) developed by Albert Sabin, dramatically reducing the number of cases. Urged on by populist campaigns initiated by the US government, the two men battled it out with their vaccines in an atmosphere of deep animosity.

When Salk's vaccine was initially given widespread use in the United States, Sabin was forced to undertake his clinical trials in the Belgian Congo and Soviet Union. Vaccinating 10 million Soviet children at the height of the cold war earned Sabin a medal of gratitude from the Russian government – but tarred the OPV as the "red vaccine" for years to come. The success of early campaigns in communist states like Cuba, and then parts of central and South America, confirmed polio's status as a curiously political disease – something that was dramatically heightened by the 2012 decision by factions of the Pakistan Taliban to ban vaccination in the North West tribal areas of Waziristan and Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province after it was discovered that the CIA had instigated a fake door-to-door hepatitis B vaccination campaign in its efforts to locate Osama Bin Laden. The situation worsened when a Kathryn Bigelow film, Zero Dark Thirty, wrongly identified the doctor in charge of the campaign, Shakil Afridi, as a polio vaccinator. The ban quickly led to a ten-fold increase in polio cases (which had been as low as six the previous year) and the shocking murders of more than 60 polio workers in the course of two years. Similar claims that information gathered by the polio campaign is used for US spying is frequently given as justification for attacks on polio workers by rebel groups in other parts of the world too. "Polio has become a very, very political issue – rather than a humanitarian one," says Sir Liam Donaldson, the former Chief Medical Officer of England who chairs the international monitoring board of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). "We need to move it back along the spectrum to becoming humanitarian again."

VICTORY IN INDIA

"A whole life alters after you get polio," says Hamid Jafari, Director of Global Polio Eradication and Research at the WHO and the man who oversaw the eradication of polio in India. "Jafari remembers treating his first polio patients in Punjab province in his native Pakistan. "Young mothers were coming to me with young infants who were paralysed, and those mothers had all of this hope in their eyes that maybe polio could be cured. They wanted me to treat their babies, but I knew they were looking at lifelong paralysis. That's heart breaking, and that's part of the inspiration and motivation that keeps you going."

Although he now heads the team in Geneva, Jafari spent six years as Project Manager of the WHO's National Polio Surveillance Project in India – working as the main technical advisor to the Indian government and managing 1,000 field staff. "India was the most polio endemic country for thousands of years, and in that context, because of its size, and because of its importance in the world, it was also a very important source of international spread of polio," he says. The country struggled under a burden of up to 150,000 polio cases at a time, with population density, poor sanitation and climate making ideal conditions for the disease to thrive. "It took an extraordinary effort to achieve eradication in India."

Success in India involved a complicated partnership of international and local NGOs working with the Indian government to employ an array of techniques that would transform international healthcare; implementing an unknown level of micro planning and satellite mapping to ensure that every house even in the most far flung community was receiving the vaccine, and deploying mobile teams of vaccinators to track transient communities by marking every person's index finger with purple ink, sometimes working at bus stops, or at sites like brick kilns where transient workers and small children could usually be found. More than two million volunteers were mobilised for each national immunisation day, setting up 640,000 vaccination booths, and vaccinating approximately 172 million children on each occasion. Driving back through Agra, after the afternoon's efforts in Sarai Khwaja, one health worker from an international NGO described the effort to eradicate the disease as the equivalent of building a mammoth shadow national health system that utilised more than 900,000 health workers.

The scale of tackling polio in India was "terrifying", says Chris Maher, a senior advisor at the WHO. The campaign went through "terribly hard times" and was often battered by repeated outbreaks and threats to funding – but it was an effort that paid off earlier this year when India was declared polio free, three years after reporting the last case - a halcyon day for the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) that was otherwise wrung out and exhausted after intense years of battling intractable problems.

In his small, neon-lit, office in the CDC in Atlanta, Incident Manager Greg Armstrong is pouring over a sequence of red DNA data, laid out like a long family tree. The data represents the genetic make up of the polio case that was spinning in a test-tube hours earlier. Now the results are in and scientists have identified the exact strain and origin of the disease. "We just got this ... we sequence every virus that's picked up and we just recently picked up a case in Somalia, in Puntland, right about here," Armstrong points to one of the maps of East Africa that covers the back wall of his office. The other wall consists of floor length glass windows facing into the main Emergency Operations Center – a mission-control room where the polio response is coordinated from banks of desks and computers facing a wall of video screens flashing maps of polio outbreaks, information about team deployments, and breaking news. Armstrong turns back to his print off and runs his finger down the list of DNA data for the latest polio case: "This came after about five months of not detecting cases and the question is, where has this virus been for the last five months? Sequencing is one of the few clues we have to that."

The team is working against the clock to identify whether the virus is from the Somali region of Ethiopia, which would be particularly troubling as the quality of the vaccination campaign there has recently been vastly improved, or whether the virus is related to a larger cluster further south in Somalia. "The answer is it's more closely related to a number of specimens down here," Armstrong points to Somalia. "So this doesn't give us any definitive answers to where it's been, but the programme implications for it are that we really do need to focus the response on Somalia."

Armstrong's job title of incident manager (a US fire service rank introduced for disaster response after Hurricane Katrina to denote the person in charge), combined with his rather gaunt and hollow eyed appearance, indicate both the importance and the stresses of the job. At the CDC polio eradication remains a top priority, even when the MERS and Ebola outbreaks are being urgently discussed by high ranking officials in the room next door. Failure would be massive blow in terms of funding, confidence – and prestige.

Failure will cast the global health community into the kind of gloom that engulfed it after the failure to eradicate malaria in the mid-80s. If polio can't make it, perhaps no one else will try. Larry Brilliant outlines the narrative of the defeatists. Since the eradication of smallpox in 1980 the world has lived with the idea that smallpox was the only disease that could be eradicated: "That's crap," he says bluntly. "When we eradicate polio, the positives consequences of that will embolden a generation." According to estimates by the US government, ten of billions of dollars have been saved by eradicating smallpox, and the same would be true for eradicating polio. The final costs of eradication can seem outrageously expensive, however, and most recently have been borne by the intervention of one philanthropist – Bill Gates.

"At the time the programme was really struggling for money. So the engagement of the Gates Foundation was a lifeline as far as financial support was concerned," Chris Maher, a former senior manager in the WHO programme, says. Gates was personally committed to polio eradication, reading all the research and asking searching questions. Success in India had indicated how far the Global Polio Eradication Initiative had come in reducing polio cases from 350,000 in 125 countries in 1988 to 400 in 2013 – yet tackling those final cases required a type of co-ordination, efficiency and accuracy that behemoth international institutions sometimes struggled to achieve. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation committed $1.5 billion to polio eradication, with the promise of $1.8 billion more by 2018 – but such an investment came with a laser like focus from its own team of technical experts.

"It brought a different sort of energy to the programme and a different level of expectation," Maher says. "It was a very good thing, but of course when you have any big new partner joining an initiative saying - hey this is great, we really want to get into this, and we want to see things done faster, then it creates a certain set of ripples that you've got to cope with." Carol Pandak heads Rotary International's polio programme, PolioPlus, and admits that the original partners (including Rotary which initiated the polio eradication campaign in the late 1970s, and remains the biggest private funder) found working with the Gates Foundation a challenging new scenario.

BILL GATES SAVES THE DAY

While Bill Gates has personally lobbied heads of government and other philanthropists to support polio eradication, the Foundation has provided much of the support for the technology behind the campaign, such as the smartphone app that allows vaccinators to be tracked in the field, and focused on two transformative areas - the vaccine, and funding. The Gates Foundation negotiated a reduced price with manufacturers for the IPV vaccine and also negotiated with the World Bank to restructure loan agreements along the lines of a buy-back scheme – providing a massive incentive for governments to continue with polio eradication. In essence, the Foundation agreed to pay off development loans of $65-$95 million given by the World Bank to countries like Nigeria, if such countries met their polio eradication targets.

Prior to these changes, polio eradication had been essentially stagnating for ten years, according to Sir Liam Donaldson, who took the chair of the GPEI International Monitoring Board - and tackling the final stages of the campaign required something of a revolution. Donaldson was astonished that there seemed to be no figure for how many children were missing vaccinations. Or rather that figure did exist, but it was deeply buried in a report under a different heading. The figure Donaldson identified, and then prominently displayed, was 2.5 million. "2.5 million missed children. How are you going to eradicate the final 1% of polio when you have 2.5 million missed children?" Middle managers complained of leadership issues and "people problems", while frontline vaccinators were sometimes unwilling to carry out their work – citing security concerns but in reality collecting a pay check without turning up.

Resolving such people problems, using surveillance data and applying the latest in satellite technology has led to ground breaking advances in Afghanistan, Nigeria and across Africa. One of the great, untold, success stories of polio eradication has been turning millions of Muslim vaccine "refusers" into participants in the programme; building a historic coalition of religious leaders, local Imams, scientists and the Islamic Development Bank in favour of childhood vaccinations. Afghanistan and Nigeria both built local EOCs to co-ordinate the campaign across all agencies, as well as the most accurate community mapping and data collection ever known in those regions. As in India, the monumental scale of investment in the Nigerian amounts to the creation of a shadow national health service. "If you pulled out the polio programme in Nigeria the Ministry of Health would be on its knees," says Omar Pasi from the CDC.

"We've never stopped polio in Nigeria, and we think if we can stop it in Nigeria, Africa will be polio free very quickly," says Craig Allen who oversees Africa for the CDC. Vaccination rates have now risen to over 80% in northern Nigeria, the highest ever.

To the satisfaction of the CDC, and on the ground health workers like Faisal Shuaib, every aspect of the polio eradication campaign in Nigeria has now been successfully and efficiently introduced to contain Ebola.

The battle is being won everywhere, it seems, except Pakistan where, it was recently announced, polio has reached a fifteen year high with 200 new cases. Aziz Memon, a Karachi-based businessman who chairs Rotary International in Pakistan and leads the charity's polio initiative in the country. He estimates that effect of the ban, and the killing of vaccinators, has meant that nearly 300,000 children have remained unvaccinated – and are now spreading the disease to other parts of the country and around the world. Worse, he lives with the consequences of a campaign that is costing the lives of ordinary volunteers: "In Karachi we have one family who have lost two daughters in this way, and now their third daughter is also going out as a polio vaccinator in memory of her sister."

In Pakistan polio coordinators have found ways around the ban – setting up vaccination spots on transit routes or regional borders, sometimes sending in vaccine with civilians, and ruefully acknowledging that it has been often Taliban officials who have quietly asked for the vaccine – knowing that it is their children who will be crippled too. Four thousand police were mobilised on the streets of Peshawar to support a vaccination day this year, and more than 200,000 people were vaccinated in North Waziristan when they fled their homes after a military offensive against terrorists. Such on the ground efforts have been matched by intense political lobbying, replacing the visible presence of international NGO's with local NGO's, highlighting funding from the Islamic Development Bank, and working with the Pakistan government, as well as opposition leaders like Imran Khan, for support across the spectrum.

Security is not the only threat to polio eradication. Outbreaks of other diseases, like Ebola, the forthcoming elections in Nigeria and the logistics of introducing IPV could all throw the polio eradication campaign off course. An estimated ten million cases of paralysis have been prevented, and more than one and half million lives saved, in the course of the polio eradication effort – but the clock is ticking in a race against time until the interest and commitment of funders wane.

For Hamid Jafari, leading the programme at WHO, the only respite is playing the occasional game of cricket. "It's very tough, it's very intense, it's very complicated, and it's very exhausting sometimes," Jafari says wearily. "But you have this goal which is the ultimate in disease control: eradication. And that is also the ultimate in equality. The imperative of this programme is that in order to succeed you have to reach everybody. You have to reach people who, no matter what their risk and their religion might be, or even their opposing views to yours - you still need to vaccinate their children."

If polio eradication is a 20th-century dream, conceived by idealists and driven by big international institutions and volunteers, it must succeed or fail in a century marked by factionalism, religious intolerance and rising inequality. It may have taken an outbreak of an even more terrifying disease, Ebola, to demonstrate the crucial role what eradicating a disease of the past is playing in containing the diseases of the future.

Correction: This article originally stated that the polio campaign used drone technology. It in fact uses satellite technology but not drones.