Korean National Highway No. 1 curls through the massive hills overlooking Seoul, one of the world's richest and most technologically advanced capitals, and then races north 30 miles and 60 years into the past. At the border of North and South Korea, coils of barbed wire and sentry boxes still line the multi-lane highway to Panmunjom, as if the Korean War had just ended. For most of the world, those three years of vicious fighting ended in peace, however strained, in 1953. But it was just a truce. Officially, the war is just in a lull.

Along the so-called Demilitarized Zone that divides the U.S.-backed, exuberantly capitalist South from the Chinese-backed, fanatically secretive Communist North, only about 2,000 yards of wasteland separate hundreds of thousands of battle-ready troops backed by enough artillery to obliterate each other within a few hours. Over the decades, sporadic gun battles have taken the lives of scores of soldiers on both sides. The Communist regime still sends spies and saboteurs and now drones south, keeping the war at a low boil. Naval and air clashes regularly erupt. Just south of the DMZ, South Korea keeps finding tunnels big enough to rush thousands of Communist soldiers south in an hour. "We stand face to face with the enemy every day," a muscular, polished-to-the-hilt South Korean soldier told a group of visiting foreign journalists, including Newsweek, at the DMZ on November 19.

"The most dangerous place on Earth," President Bill Clinton once called the Korean Peninsula, and it's probably gotten more dangerous since he said that two decades ago. Following a searing U.N. condemnation this month of its Soviet-style gulags and other human rights outrages, Pyongyang threatened a fourth nuclear weapon test.

Such grandiose brinksmanship is typical of the regime. Last year, North Korea rattled its missiles at Hawaii, Guam and Washington, D.C. (no matter that it can't yet reach them) as well as South Korea. Faced with such threats over the years, the U.S. has embraced its own doomsday scenario. After meeting with the U.S. commander in South Korea when he was defense secretary in 2012, Leon Panetta said he had a "powerful sense that war in that region was neither hypothetical nor remote, but ever-present and imminent," he recalls in his memoir. If the Communists invaded en masse, he wrote, the U.S. would use "nuclear weapons, if necessary."

All of which makes Korea a kind of Cold War theater of the absurd, frozen in amber. Outright war is unthinkable, suicidal. Yet both sides talk about a future "reunification" based on the triumph of one side over the other. The Communists seem to think they can frighten the South, not to mention Washington, into capitulation, with their military might—puny by U.S. standards. And in Seoul's version, an economic collapse looms in the North, due to its profligate military spending, particularly on nuclear weapons and ICBMs, as its agricultural industry implodes. It's planning to step up and take over.

But most observers think China will never permit a North Korean collapse, in part because it would propel millions of refugees into its territory, not to mention open the gates to a U.S -South Korean advance to its doorstep. Nevertheless, officials in Seoul recently showed off its Ministry of Unification, which has an annual budget of about $180 million and 300 staffers (augmented by 300 government advisers) dreaming about the future, "so people won't be caught off guard when it actually happens," as a slideshow there instructed the visiting reporters. Plus, according to South Korea's JoongAng Daily, the government estimates that "a possible sudden collapse of [the North Korean] government or another kind of rapid and unexpected reunification" could cost as much as $500 billion.

In response to such magical thinking, a reporter from China lectured a ministry researcher, "This isn't like buying a house, you know. You can't plan a budget for something like that."

North Korea long ago gave up churning out propaganda portraying the South as poverty-stricken, a message that would have been greeted with bitter shrugs from the 1990s on by people so hungry they were periodically reduced to eating bark and roots. Thanks in part to letters and calls back home from the approximately 27,000 people who have managed to escape, mostly through China, over the past two decades, millions of North Koreans now know the South is far, far better off, in so many ways. The local gendarmes long ago stopped trying to block the incoming mail from such refugees, which often includes some cash. Now they just take a cut.

Three North Korean "defectors," as Seoul calls ordinary refugees and high-ranking turncoats alike, made it clear recently that Seoul's booming economy had little to do with their decisions to flee. It was their lives of unrivaled oppression, cruelty and frequent starvation. "I tried to defect for about 10 years," Lee Sung-sili, 47, told the assembled foreign journalists. "Every time I got to China, I was repatriated. I finally got out [by continuing through China] to the Mongolian desert" in a group of eight, she said through an interpreter. "We had to drink our own urine to preserve ourselves."

Dabbing at tears, Lee recounted how she had served as a nurse in the Korean People's Army but was impoverished when she was discharged and had to beg and scavenge for food. Men took advantage of her. Living on the street, she gave birth to a daughter.

When she was returned from China after one of her failed escapes, she was beaten and tortured with scalding water, she said, opening her blouse slightly and showing the scars. "This all happened in front of my 2-year-old daughter. When she cried, they hit her, too." On her ninth and successful escape, her Chinese go-between sold her daughter "into human trafficking, for about $3. Today I don't know where she is."

Sitting beside Lee and looking as frail as a dying sparrow, 24-year-old Choi Yoo-jin told an equally harrowing story. In 2008 she graduated from high school and was dispatched to a hard-labor unit doing highway construction. "In 2011 I tried to defect," Choi said softly through an interpreter. "I had an aunt who suggested we go to China together. We could earn money and send it back home.… She betrayed me.… I was sold into a forced marriage. He was the age of my father, in his 50s. I wanted to die.… Later he dissolved the marriage and sold me to someone else."

Eleven times, Choi said, she was sold from one Chinese man to another, before she escaped and made her way out of China last year with the help of Christian activists. "I can't tell you everything," she said in a near whisper. "I have deep psychological scars." What does she hope for now? "My only wish is to see my family again and have a meal with them," she said, wiping away a tear.

Some 70 percent of the escapees from North Korea are female. Indeed, Korea's women on both sides of the DMZ carry outsized burdens, some dating back to the Japanese occupation of the peninsula from 1910 until its defeat in World War II in 1945. About 200,000 Korean women were forced into sex slavery to service the Imperial Army's troops. The few remaining survivors of that horror complain bitterly that Japan refuses to offer restitution and a full apology. Every Wednesday at noon, they and their supporters demonstrate outside the Japanese Embassy in Seoul.

A third refugee on the panel, who asked that her name not be revealed, said millions were dying of starvation in 1995, when biblical-level floods swept the country. "My father was one of them," she said, breaking down and weeping. The scarce food went to the army. "The rest of the people had to live off bark and the roots of plants.… Even small portions of food we were given were stolen by the army." In 2011, after being sent to a work camp for ideological "offenders," she decided to escape, walking days and nights into China, she said. From there she made her way via the Christian underground to Thailand and thence to the South Korean Embassy.

Adjusting to South Korea was "difficult," she said. "I had lived in a very isolated society, dedicated to Kim Jong Un," the grandson of Kim Il Sung, the "Great Leader" who ruled the North from 1945, when he was installed by the Soviet Union, until his death in 1994, after which his son Kim Jong Il assumed the Communist throne. "It was a big adjustment to live in a capitalist society," she said.

Seoul, with its high-tempo entertainment districts, its swarms of luxury cars, its four-star hotels and expensive restaurants, and its fashionable young men and women toting cutting-edge technology around the downtown's architecturally striking skyscrapers, must come as a shock to someone from the bleak and destitute North. The South Korean government offers them a small room, a modest stipend and vocational training.

It's a hard go. "It was very hard for me to work as a nurse in South Korea," said Lee Sung-sili, who eventually became a prosperous host of a TV program, focusing on North Korea's human rights record, called I Am Coming to Meet You. "I learned a very different kind of English," she said through an interpreter. "Instead of following my dream, I had to work very hard to survive."

"The biggest challenge was language," echoed Choi Yoo-jin, who is now taking computer courses. It wasn't just her lack of English. "South Korean has the feel of a foreign language," she said through her interpreter. "It's basically the same language, but yet another. If the division continues, [North and South] won't be able to talk to each other without an interpreter."

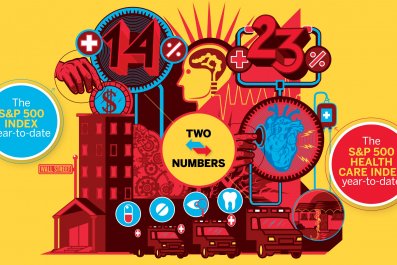

These fortunate few know they have escaped hell, but soon learn they have not landed in paradise. South Korea's frenetic economy is exacting a cruel toll even on young people who grew up there. Suicide is the leading cause of death for South Koreans between the ages of 10 and 30, for whom failing a school examination is a professional and social death sentence. In 2012, over 14,000 young people took their lives, an average of 39 per day, according to government figures. Suicide ranks second as a cause of death for people in their 40s, behind cancer. Old people, retired with little or no pensions and abandoned by children they expected to care for them, are killing themselves in record numbers, too.

"Suicide is everywhere," Kim Young-ha, author of the novel I Have the Right to Destroy Myself, wrote in The New York Times last April. Everyone seems to have known someone who gave up and leapt to their death, he and others say, often into the swift, half-mile-wide waters of the Han River, which cuts through Seoul on its way north to the DMZ, where it empties into the Yellow Sea.

Unlike in Manhattan, L.A. or even stiff-lipped Tokyo, psychiatric care is widely considered taboo in proudly self-sufficient South Korea. "Many think that when someone is suicidal he simply lacks a strong will to live; he's weak," Kim wrote. "There's little sympathy or interest in probing below the surface. Small steps, he noted, are being taken by local authorities in Busan, South Korea's second largest city, to monitor depression among its citizens, but it has a population of just 3 million, compared with Seoul's 22 million.

More bad news is on the way: Birthrates are falling "because the country's young people are increasingly delaying or giving up on marriage and having children due to a lack of government support and financial means," said a November 24 report in The Korea Times, citing figures from the National Assembly's Budget Office. "As a result, the economy could fall...due to the low birthrate and the aging population."

All of which might temper the hopes of government officials that the end is near in the North, and fuel the delusion of Communist hard-liners that the South is vulnerable to intimidation, if not outright military conquest.

And so the cold war continues. Along the DMZ, battle-ready troops from both armies practice maneuvers within a mortar shot of each other. Armed sentries stare at each other across the so-called "Truce Village," the collection of huts at the exact center of the Joint Security Area, where both sides meet to exchange unending, sometimes bombastic demands.

Late on a recent day, the autumn sun bathed the DMZ in amber. On each side of the border, North Korean and South Korean gift shops were selling T-shirts and hats to visitors with exactly the same slogan: "Korea Is One."

Correction: This article originally incorrectly stated that that the Ministry of Unification has 200 staffers (augmented by 600 government advisers). The Ministry of Unification has 300 staffers (augmented by 300 government advisers).

Correction: This article originally read " the government has budgeted as much as $500 billion for 'a possible sudden collapse of [the North Korean] government or another kind of rapid and unexpected reunification.'" It now reads, "the government estimates that 'a possible sudden collapse of [the North Korean] government or another kind of rapid and unexpected reunification' could cost as much as $500 billion."