Raindrops blurred the windows of the maroon Pontiac van as it rolled to a stop near an interstate on-ramp in Knoxville, Tennessee, one dark March morning in 1991. "Stay tucked," John Cook told his wife, Yvonne, who stirred from her sleep next to him. "I'm going to check the map."

It was just after 5 a.m., and the Wisconsin couple were already 12 hours into their Diet Coke–fueled drive to North Carolina to visit friends. They planned to drive straight through dawn, and had removed the backseats, replacing them with a bedroll so one could rest while the other steered. From behind the wheel, John clicked on the overhead map light. Rain fell so heavily that Yvonne couldn't see through the glass. When she heard the first blast, it seemed to come out of nowhere. Then there was another. She saw John, now slumped over.

A man with a gun appeared. He was trying to smash the driver's side window and unlock the door. "Get him out of the seat!" he yelled at Yvonne, getting into the car. She unbuckled her husband, catching a look at the intruder's face as the dome lights came on. John had been shot twice in the head. His left ear bled. He fell into her lap.

On the floor of the van between the front seats, with her husband dying in her arms, Yvonne could see the gunman's profile. He took control of the van, and sped off while holding the .22-caliber rifle to her head, until he finally pulled off the road. "Shut up," he told her. "Don't look at me."

He demanded money, and told Yvonne to get out of the van and kneel next to John's body. A car approached. Startled, the assailant got back in the van and sped away, leaving Yvonne in the rain at the edge of a stranger's driveway, her husband's body at her feet.

That, according to court documents, was how Yvonne would remember the event. But memory—to the judicial system's growing disconcert—can be flawed. In the weeks after John's murder, investigators could find no proof leading to a suspect and no fingerprints. They had only Yvonne's memory, and it had holes. She struggled to recall the face of her husband's killer. She told a detective she wasn't sure she'd ever be able to identify the man who did it.

Two years passed. Then five. Then eight. The case went cold.

One day, a decade after the crime, an arrest was made. When Yvonne saw a photograph of a suspect in the newspaper, she no longer doubted her ability to recall. She was certain now. The man in the photo, she said, was him.

The TV Rapist

If you were assaulted or saw a loved one killed and you caught a glimpse of the face of the person who did it, you might feel certain you would never forget it. It's hard to imagine that key details of such horrific moments could vanish from the mind, but 30 years of scientific research into how memory works proves that recollections are as taintable as any crime scene—and are often not as meticulously preserved.

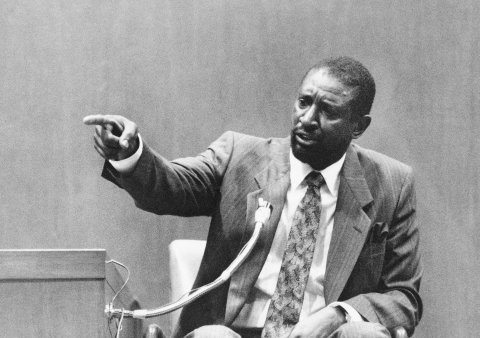

In the 11 years since the trial and conviction for the murder of John Cook, a growing push within the judicial system by scientists, lawyers and judges for a better understanding of how human memory works has revived the Tennessee case, as well as others nationwide. Questions involving Yvonne's ability to remember the attacker have led to arguments over whether that trial was fair, and this year the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which handles four states including Tennessee, agreed to reconsider the case. "It's taken courts a while to get to the point where they can find the science [on memory] reliable," says Knoxville defense attorney Stephen Ross Johnson. His client, Howard Walter Thomas, 43, has been in prison for the past 14 years for the 1991 murder of John Cook.

Memory, as experts have been trying to teach judges and jurors, does not function like an iPhone camera recording. Memories can not only be deleted; they can be altered or invented without you even realizing it, as shown in a study published last year in the International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, which involved 861 U.S. soldiers enrolled in a survival school. As part of training, they endured abusive interrogations. Afterward, many were shown a photo of someone who looked nothing like their interrogator, and interviewers insinuated that the person depicted was the culprit. Eighty-four percent of the soldiers misidentified their interrogators after being misled, and some also remembered weapons or telephones that never existed.

An extensive body of research with similar findings has become increasingly perplexing for the nation's judicial systems, leading the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to release a sweeping report last month calling for an overhaul of how the courts and law enforcement deal with one of the most powerfully persuasive pieces of evidence that can sway a jury: eyewitness identification. Research has shown that leading questioning or suggestive behavior by psychiatrists, police or acquaintances, as well as accounts in the media, can result in "planting" false memories in the mind of a witness. In some cases, this can lead witnesses to believe they saw incidents that never occurred. In lawsuits recently filed against Castlewood Treatment Center in St. Louis, plaintiffs have argued that therapists used hypnosis and psychiatric drugs to recover "hidden" abuse memories that turned out to be false.

Between 60 and 80 percent of psychologists and other mental health professionals still believe therapy can retrieve repressed memories, as noted in a 2013 study in Psychological Science. Yet many scientists and mental health professionals now believe that research does not support the notion that traumatic experiences can "disappear" from one's memory only to be recalled years later in evocative detail. Here's the more likely scenario: Those traumatic memories were instead conjured up as false memories after leading questioning by a therapist.

When it comes to long-term recollections, most memory researchers believe modifications are constantly being made, while gaps in narrative are filled in with experiences and expectations—not the actual events. Stressful situations (especially those involving a weapon), like Yvonne's abduction, can be particularly vexing for the memory: They can take a person's attention away from an attacker's face and possibly lead to a skewed or mistaken identification.

Unsettling as it might be to admit it, the mind is really a muddle of distorted memory associations, further complicated by the distracting details of the moment. For most of our country's judicial history, this understanding has been largely absent from courtrooms, but a string of shocking cases across the world over the past three decades has ushered in debate, discussion and, finally, the revamping of national laws on the issue.

Take Donald M. Thomson, a psychologist and attorney in Australia who was arrested for assault and rape in 1975. The night before his booking, Thomson had appeared on a television show discussing his research on the flaws of eyewitness testimony. As the show aired, the woman who would later identify Thomson as her attacker was being raped in her apartment. Thomson's alibi was solid—the television show had been live. The victim later admitted she had been watching the show before she was attacked. Authorities dropped charges against Thomson after realizing the victim had confused his face on her television screen with her rapist's.

There have been 318 wrongful convictions overturned by DNA evidence since 1989. In most of those cases, the eyewitnesses who testified felt confident in their memories when under oath on the stand. Yet eyewitness testimony contributed to 72 percent of those wrongful convictions, according to the Innocence Project, a nonprofit legal and public policy group.

Gary Wells, a professor at Iowa State University who has been working on the issue of lineups and eyewitness identifications since the 1970s, says that for a defendant, it used to be, if "you get mistakenly identified by an eyewitness, you're just going down. There was pretty much nothing definitive enough to trump the eyewitness account." But when DNA exonerations began seeping into the legal system in the 1990s, more courts began to ask: Why are so many eyewitness accounts misfiring?

That question has prompted some courts to revamp how such evidence is handled. In 2011, the New Jersey Supreme Court released detailed jury instructions, requiring consideration (usually at the end of a trial) of the crime's duration of time, a witness's level of stress or distraction, distance from the event, lighting at the time, intoxication, a focus on a distracting weapon, if there were possible racial challenges (since research shows that people make more mistakes trying to identify strangers of races different from their own) and exposure to information that may mislead the memory.

In 2012, the Oregon Supreme Court also mandated new procedures for allowing eyewitness identifications in court, requiring determination of whether "suggestive" tactics like cueing the witness or bolstering an identification were used by law enforcement. Meanwhile, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court has been positioning itself to follow suit after three years of closely examining the issue and hearing oral arguments this past September in four cases involving eyewitness testimony. Eleven states now require law enforcement officials to follow more careful procedures when obtaining eyewitness identifications, according to the NAS report, but policies and practices vary widely by state. Despite growing awareness about memory science, the intricacies of how it works still remain largely unfamiliar to many jurors, witnesses, attorneys, judges and law enforcement officials.

'I See Your Eyes Drifting'

In 2003, when Howard Walter Thomas was on trial for the murder of John Cook, such shifts were only beginning to enter into the court system. When Yvonne Cook got down from the witness stand, stood in front of Thomas and said, "You're the person that murdered my husband," few in the courtroom would have had reason to doubt her sincerity. But they missed an opportunity to doubt her ability to recall.

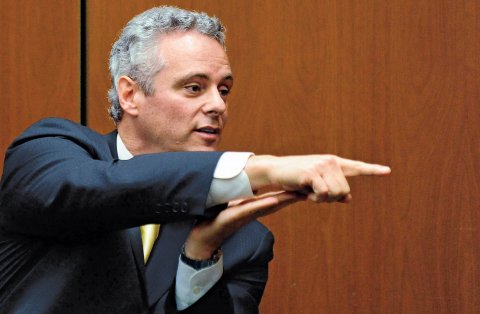

Elizabeth Loftus, a memory expert, had reviewed the case files at the time, and was brought into a pretrial hearing to explain the complexities of eyewitness testimonies and the fallibility of memory. But at trial, the judge barred her testimony.

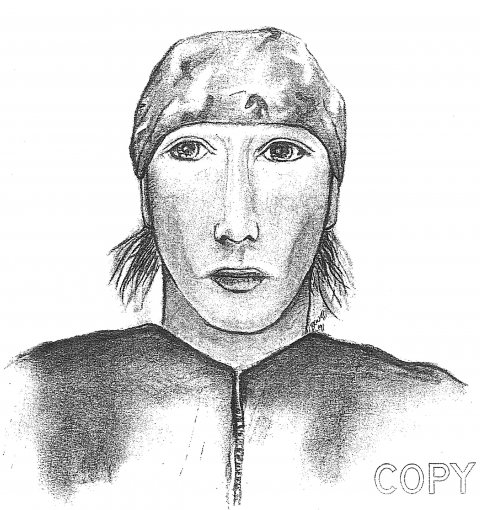

The day after that attack in 1991, Yvonne described the suspect as a white male who looked so young he had probably not even started shaving yet. She said he had sharp features and a slender frame. He wore a bandanna, probably olive green. But that wasn't enough to pinpoint a suspect.

After returning to Wisconsin, she began seeing a psychiatrist, who suggested that she undergo hypnosis to try to remember any details she may have "blocked out." Desperate to help police solve the murder, Yvonne visited hypnotist Dale Sternberg, according to court records. Sternberg noted that Yvonne had "developed a mental block in recalling details of the assailant's face," and she was frustrated that her vague recollection was not sufficient enough for investigators.

After four sessions, Yvonne met with a police sketch artist and helped compose an illustration of a long-nosed man with peach-yellow skin, hollow cheeks, a thin upper lip and tails of dirty blond hair peeking beneath his green bandanna.

Still, the illustration produced no hard leads, and Tennessee police continued to send photo lineups to Yvonne in Wisconsin. She received around 36 pictures (in six sets of six, known as "six-packs") along with video lineups, which she viewed with a detective.

In the years since the Cook murder investigation, a growing body of research has altered how some police lineups are now conducted. The NAS report supports "double-blind testing," first introduced by Wells, in which the investigator presenting the lineup does not know who the suspect is (lessening the potential risk for cueing the witness) and where instructions are given to the witness explaining that the actual suspect may or may not be in the lineup at all.

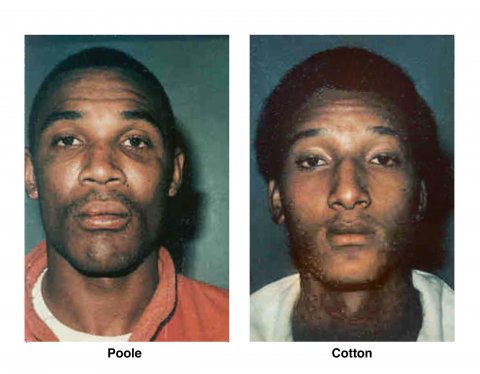

The push to implement procedures like these stems from problematic cases like the 1984 rape of North Carolina college student Jennifer Thompson. During a photo lineup with police, she pointed to a man, Ronald Cotton, and said, "I think this is the guy." Later, she asked detectives, "Did I do OK?" To which one replied, "You did great." That reinforcement made her more confident in the choice, and when she was shown a live lineup with Cotton in it, she chose him again. Cotton served a decade in prison before he was exonerated by DNA tests, and the case led North Carolina to adopt revised rules for police lineups.

But suggestive behavior by law enforcement is still a widespread problem, according to Loftus, now a professor of social ecology, law and cognitive psychology at the University of California, Irvine. She has testified in 285 cases since 1975, and remembers a California case in which an investigator said on tape to a witness viewing a six-pack, "I see your eyes drifting" down to number six. "The witness obliged and eventually globbed on to number six," Loftus says, "and it turned out to be the defendant."

Among the men Yvonne viewed in the video lineups, only one stood out. His body language seemed similar to that of the murderer. "I'd like to hear his voice," Yvonne told an officer, who forwarded the message on to Knoxville investigators. According to court records, police never followed up on the request.

Her Husband Dying in Her Arms

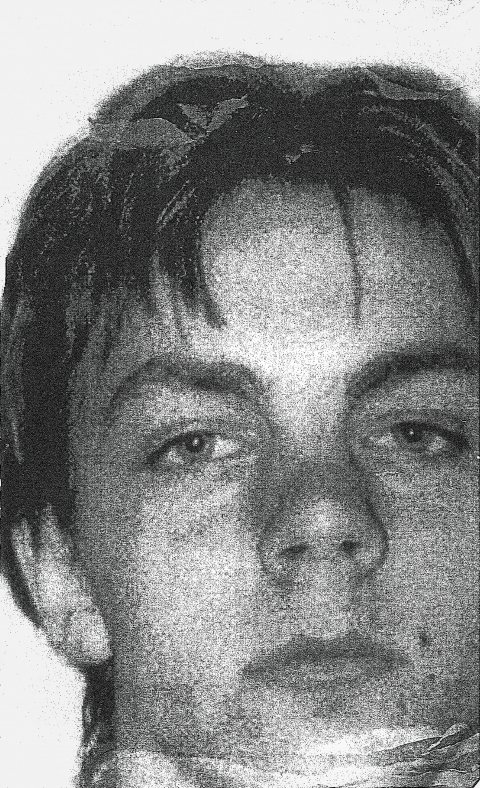

In 2000, nine years after the murder of John Cook, Knoxville police received a tip from Mary Storm of Atlanta, who told them she had recently talked to her brother, Earl Storm, about the cold case. On his deathbed, she said, Earl claimed he knew of two people with a connection to the murder: his step-grandson, Ernest Salyer, and Salyer's friend, Howard Walter Thomas.

The police tracked down Salyer as a suspect. He told them that he had been best friends with Thomas since they were 14 or 15, and that on March 23, 1991, when both were in their early 20s, he received a call from Thomas asking to pick him up at a car wash.

Salyer said he took Thomas home with him, where he asked his mom to wash Thomas's clothes because his friend had "been in a fight." Salyer's mom put Thomas's clothes in the laundry, and gave him another outfit. Later, they went to Salyer's grandmother's house to stash Thomas's .22 rifle. The grandma eventually burned Thomas's clothes.

In her home one evening in May 2000, Yvonne received a call from a detective she knew. "I have some good news," he said. At that moment, she knew police had made an arrest. Relief swept over her. She had been waiting for this day for nine years, and now she had a name.

Soon after that call, a friend of an acquaintance sent Yvonne a copy of the Knoxville News-Sentinel, with the headline "Knox man charged in '91 murder of motorist." It featured a photo of Thomas underneath a photo of her dead husband. In that moment, she knew. She said she remembered that face.

The man in the photo had a mustache and beard, unlike the smooth, teenage skin from her past descriptions. He also did not really look like the man in the police sketch. And, finally, he was not the person in the lineup back in 1992 whom she had asked to hear speak. His face was fuller, and his nose more bulbous, with a rounded chin. But she was convinced it was him.

In court three years later, Salyer, his mom, grandma, sister and ex-wife all testified against Thomas, each claiming to know pieces of evidence that pointed to his guilt. Salyer and his ex-wife said Thomas had also allegedly confessed to them separately that he had accidentally killed Cook, while shooting randomly at cars that morning, according to court transcripts.

Attorneys for Thomas would later argue in their appeal that the prosecution relied on "testimony from witnesses who were, at best, admitted accomplices with a motive to claim that Thomas, not Ernest Salyer, was the shooter." In other words, they were out to protect Salyer—who had been a suspect until he incriminated Thomas and was never charged.

Taken alone, that evidence would probably not have been enough to convict Thomas, says Johnson, his attorney. But Yvonne's eyewitness account was a powerful clincher. Had the jury heard from Loftus, who had reviewed the case, they may have better understood how memory works: that Yvonne's testimony might have been unreliable since her husband was dying in her arms and she had a gun pointed at her head—not to mention the muddying effects of the hypnosis, the lapse of time between the crime and the identification, and the suggestive newspaper article.

But at the time, Tennessee did not allow experts on eyewitness testimonies in courts, a rule based on the idea that instead of clarifying the science of memory, experts like Loftus could be wielded by deceitful lawyers to unfairly sway juries. In 2007, Tennessee and other jurisdictions began authorizing courts to permit expert testimonies on eyewitness misidentifications.

Since 1983, there have been a string of reversals for cases in which courts excluded such expert testimonies. The first was an Arizona case in which eyewitness testimonies led to Dolan Chapple's conviction on three counts of murder; the ruling was overturned by the Arizona Supreme Court, which stated that the initial judge had "abused his discretion in excluding expert testimony concerning eyewitness reliability." Similar reversals followed in California and Washington.

Wells says the NAS report and recent stances taken by the courts in New Jersey and Oregon on eyewitness testimonies will have a ripple effect, particularly in reevaluating cases from decades before, when the science of memory was misunderstood and not widely accepted. "There's enough pressure now that this will have a very big impact," Wells says. "The action is going to occur at the appeals and state supreme court levels."

Now Thomas and his attorneys await oral arguments at the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, hoping his case will be the next domino to fall.

But it might take longer for science, and even the courts, to persuade the rest of us that our memories are slippery. After all, we build our identities from memories stitched together over a lifetime. We craft our belief systems and values from them, along with the instincts that we trust.

"Look at him very closely," the prosecutor asked Yvonne in the court trial of Thomas, the man the police, the prosecution and the public thought killed her husband, and robbed and attempted to kill her. "Do you have any doubt at all about this being the person?"

"No," she answered, looking directly at Thomas. "I do not."