It begins with a speedboat. The pilot is crawling upriver. The scenery suggests an estuary. Aside from the grassy bank where the soldiers have parked their pick-ups, the river has no shore, just ankle-deep mud flats shelving up to a curtain of mangrove, behind which lies an endless, still and inky swamp.

The pilot spots the soldiers, turns in, cuts the power and glides. The soldiers, 25 of them, wade into the water up to their waists. They form a line stretching to the shore. One jumps aboard and passes a large black and brown canvas bag to a man in the water, who passes it over his head to the man behind, and so on, all the way to the pick-ups. From the look on the soldiers' faces and the strain on their arms, the bags are heavy, perhaps 20 kilos, making a boatload of a round ton. After they unload the last bag, the soldiers push the boat back out into the current, and the pilot fires his engine, turns in a lurching swirl and heads back downriver. The soldiers climb into the pick-ups and sit on top of the bags. The film cuts.

I once drove deep into the Sahara to hear how someone landed a Boeing 727 in eastern Mali in November 2009, dropped off 10 tons of South American cocaine and then torched the plane. Another time, I took a taxi out to a village in Guinea-Bissau on Africa's western tip to hear a 62-year-old woman describe how one night in December 2011 a plane landed on the road outside her house and unloaded two tons more. I returned in September when I heard about the speedboat film. It was less spectacular than the other drops but, since the delivery happened on June 23 this year, it was evidence that large-scale cocaine smuggling was continuing. And, since the soldiers had been caught on film smuggling cocaine, it was the most definitive proof to date that Guinea-Bissau's military – or parts of it, at least – were one of Africa's biggest drug-smuggling outfits.

That also made it the kind of film people died or killed or even staged a coup over. Since all these things happen regularly in Guinea-Bissau, I can say merely that the film was shot in a coast creek near a military base. I cannot say who made it, or why, or even show it, since the shot angle might identify the cameraman. The only reason I can write about how cocaine smuggling is ruining an area of Africa the size of Western Europe is because I don't live in Guinea-Bissau. I have agreed to identify almost no one who spoke to me.

The story of cocaine helps explain how Islamist militant groups in the Middle East and Africa, including al-Qaida, gather popular support. It also accounts for how they earn billions of dollars a year. It provides one reason why Africans are often so cynical about foreign assistance: because Western aid workers, diplomats and soldiers frequently find themselves, if not quite in business with drug smugglers, then their political, financial and military backers. The thriving smuggling route from Latin America through Africa to Europe also explains why cocaine in Europe is now as middle class as Volvos or weekend farmers' markets.

This is not another story about how drugs can screw you up. This is a story about how Europe's appetite for drugs screws up the lives of hundreds of millions of others. The closer you look at the cocaine business, the clearer it becomes that every time one of us – or our lovers or colleagues or children or their friends – buys a gram, we are helping keep an African country in the sewer and feeding the sort of groups that like to behead hostages on TV. This is a story about lines, yes, but less about the lines racked out every weekend on coffee tables and in nightclub toilets in London or Madrid or Frankfurt or Tel Aviv than those other lines, those that run dead straight from that to this. "You know, this is not some small game," a Western diplomat in Guinea-Bissau once told me."This is about financing terrorism on Europe's southern border, about drug money from Guinea-Bissau and Mali being used for a bomb in London."

THE MAN IN BISSAU CITY

Bissau City subsists in a state of exhausted collapse. The architecture is late Portuguese colonial – stately concrete buildings with generous ceilings, overhanging balconies and leafy courtyards – but it is crumbling fast. The need to move as little as possible in the heat means the place takes no time at all to get to know. Everyone arranges themselves within half a mile of each other in the city centre, around a handful of cafés and restaurants serving octopus salad and chilled carafes of vino verde.

I first began visiting Guinea-Bissau in September 2012, five months after General Antonio Indjai, a corpulent chicken farmer whose family connections catapulted him from private to general during Guinea-Bissau's civil war in the 1990s, had overthrown the government, installing a replacement government as his personal front. Political calamity had been accompanied by economic collapse and, in that vacuum, diplomats estimated the amount of cocaine moving through Guinea-Bissau had doubled to 60 tons a year since Indjai's coup. The trade was worth twice Guinea-Bissau's official GDP.

At his offices in a backstreet in Bissau City, I met Joao Biague, the 44-year-old national director of the judicial police and Guinea-Bissau's lead anti-narcotics officer. Joao had no money to run an effective operation. Once, the UN Office for Drugs and Crime had given his squad five cars but they had suspended their support after Indjai's coup and, without it, the judicial police had no gas money. Joao did have about a dozen mobile phones and around 20 men, whom he deployed in the bars and cafes around town.

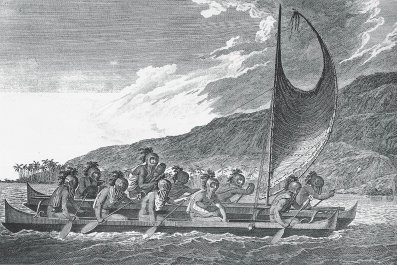

With no resources to stop the trade, Joao spent his time studying it. Cocaine, he discovered, had been transported across the Atlantic for thousands of years. In 1992, tests on several 3,000-year-old Egyptian mummies found traces of cocaine and nicotine, both of which originated in the Andes, suggesting not only that the trans-Atlantic drug trade was several millennia old but that Egyptians or Africans crossed the ocean 2,500 years before Christopher Columbus.

In the 16th century, Spaniards and Portuguese colonisers had noted how South Americans chewed the coca leaf to suppress appetite and boost energy.

The cocaine alkaloid was first isolated in Europe in 1855 and, for a few decades, it was used by doctors as an anaesthetic, proscribed by Sigmund Freud as a mood enhancer, given to children as a treatment for toothache and even included in the original recipe of Coca-Cola, which fused the drug with the kola nut. But attempts by southern American plantation and factory owners to improve the productivity of their black workers by giving them cocaine had, by the early 20th century, led to a string of stories in the New York Times about "negro cocaine fiends", who murdered and raped at will.

The backlash against cocaine, and its consequent prohibition in 1914, suppressed its use for half a century. But, in the late 1960s, Colombian growers began tapping the new American appetite for drugs. President Richard Nixon's declaration of a "war on drugs" in 1973 did little to dent demand. In fact, by the turn of the millennium, the cartels had discovered that their business growth was flat-lining, not because of efforts to stop them but because the Northern American market was saturated. That, said Joao, was when the cartels realised the European market was still comparatively under-developed and that, half-way to Europe, within range of small planes and fishing boats, were a series of eminently corruptible African countries with little in the way of law, government, airforces or navies.

In 2004, fishing trawlers, go-fast powerboats, small jets and cargo twin props with custom-enlarged fuel tanks began shuttling across the Atlantic. "Highway 10," so-called because the route roughly followed the 10th parallel, was born. At the beginning of the decade, Europe's cocaine market was a quarter of its American equivalent. By its end, the two markets matched each other at 350 tons a year. There are now 14–21 million cocaine users in the world, equating to one in 100 Westerners, rising to around three out of 100 in Spain, the US and the UK.

Africans rarely own the drugs they move; their Latin American, Middle Eastern and European bosses tend to reserve ownership for themselves. But transporting is lucrative work nonetheless, and the syndicates quickly recruited customs officials, baggage handlers, soldiers, rebels, government ministers, diplomats, even a Prime Minister and President or two.

To keep ahead of the law, the traffickers switched routes constantly, and quickly extended their reach across the continent. Soon, every African country with language in common with Latin America – Angola, Cap Verde, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique – had become a trafficking hub, as were all of Africa's biggest airports – Nairobi, Lagos, Johannesburg and Cape Town. Among the airlines, Royal Air Maroc, which linked Brazil with North and West Africa and Europe, became a smugglers' favourite, as did Africa's biggest, South African Airways. In 2009, in the first of five cocaine busts for the airline in two years, an entire 15-person SAA crew was arrested at Heathrow accused of smuggling close to half a million dollars of the drug.

The cartels were especially drawn to Guinea-Bissau. It had a coastline of a thousand hidden creeks and 88 islands, some with their own colonial-era air-strips. But with a population of 1.5 million and an average per capita income of $500, the country was too small and too poor to afford boats for its navy or planes for its airforce.

When the traffickers first arrived, said Joao, "they called themselves businessmen. At first we didn't understand because there was no business for them to do here." The first most people in Guinea-Bissau heard of cocaine was in 2005 when farmers on the coast outside Bissau City found sacks of white powder washed up on the beach and, thinking it was fertiliser, sprinkled tens of millions of dollars of the drug on their crops. The plants died, but, within a year, cocaine was a mainstay of Guinea-Bissau's economy.

Perhaps the biggest hindrance to Joao's work was that as a state employee, ultimately he worked for Guinea-Bissau's biggest cocaine smuggler, General Indjai. Joao had had death threats and when I met him, he told me he was on the point of quitting not just his job but his country too. "Look, I don't know about the future of the country," he said, "but I can tell you what I plan for my future. No country that has been through this has been able to fix it and if I cannot achieve what I want, there's no need for me to stay." A few months later I heard he had quit and moved to Italy.

THE MALI PROBLEM

For years, foreign diplomats in West Africa have shied away from addressing the problem in favour of simply working around it. Mali sits across another key cocaine trafficking route but I've never found a single diplomat there who knew much about African drug smuggling beyond the bare facts of the "Air Cocaine" Boeing. The Malian journalist Cheikh Dioura told me that despite signs of an exploding international trade, most diplomats remained pre-occupied with managing generous foreign aid programs.

That wasn't altogether surprising. Before President Amadou Toumani Touré abruptly quit in April 2012, he had been a favourite of foreign donors in Africa. The story diplomats told of Touré – known by his initials "ATT" – was of an army officer who overthrew a dictator in 1991, then handed power to a democratically elected civilian president, then, 10 years later, legitimately won an election. It was an unusual narrative of democratic West African leadership and Westerners loved it. Foreign aid rose to 50% of the government's budget under Touré. Aid workers held up Mali as an example to the continent. US Special Forces conducted annual counter-terrorism training with the Malian army. "The country is considered one of the most politically and socially stable countries in Africa," read the World Bank's 2007 assessment. "One of the most enlightened democracies in Africa," said USAID in 2012. Dioura had a different take on his former president: "Amadou Toumani Touré," he said, "was the biggest drug trafficker of all."

Dioura had a friend in the Malian secret service, a colonel who was covering the region when the Air Cocaine plane was discovered in the desert. The colonel agreed to meet. A small man in scruffy plain clothes, the only clue to his identity was a neat military moustache.I began by remarking that the stories I'd heard of the scale of trans-Sahara cocaine trafficking seemed too wild to be true. The colonel snorted.

"There are convoys every Friday!" he said. The colonel described trans-Saharan processions of 15 to 22 cars that followed the old Tuareg caravan routes across the desert. In each cab was a driver and a fighter. As many as three convoys were en route at any one time. "Everyone knows this!" said the colonel.

The colonel's description tallied with that of a 32-year-old convoy driver, who said half the cars in a typical convoy carried drugs and half provided security. Assuming a light load of half a ton per truck, and a minimal schedule of one convoy a month, that's still 48 tons of cocaine a year – worth around $1.8 billion in Europe.

The driver said the man who ran the convoy from Mali's easternmost city of Gao was an Arab called Oumar who had gathered around him 100 young men in pimped-out 4x4s who liked to smoke hashish and tear around in their cars. "The drivers are gone for a week," said the driver. "When they come back, they have big parties in the desert – girls, music, roasting sheep over big fires, spending money like water. Then they're gone again." In an attempt to lower their profile, Oumar built 25 high-walled villas in a neighbourhood in Gao to house his drivers, but the plan back-fired. The townspeople of Gao immediately nick-named the place Cocainebougou, or "Cocaine City."

Especially worrying for Mali's foreign aid donors was that Cheikh, the colonel and the driver all maintained that the smugglers were in business with government officials and Malian soldiers. The driver said the corruption went to the very top. "Oumar calls President Touré direct if he has any problems," he said. The colonel agreed. "It went all the way to Touré," he said, adding however, that he considered Mali's former president something of an accidental drug baron.

Mali's Tuaregs had staged intermittent rebellions in the north throughout the country's 50-year history. Touré's way of dealing with them, said the colonel, was to buy them off. He recruited Tuareg commanders into the army and gave them fat salaries and plenty of perks.

After they mutinied in 2006, Touré gave the Tuaregs even more, allowing them to run their territory as a highly corrupt, semi-autonomous state. The clan leaders diverted aid money intended for schools, roads and irrigations projects. They also took a cut from the cocaine trade.

Once the Malian state was sanctioning criminality, it was a short step to taking part in it. Hundreds of millions of dollars were kicked back to government officials and soldiers. As head of state, Touré found himself, in effect, in business with drug smugglers – as did, by extension, the foreign donors who funded him.

DRUG-FUELLED REVOLUTION

West Africa was rotten with drugs, its governments corrupt, unstable and unpopular, and much of this shaky edifice was supported by Western aid – a perfect environment for a purifying Islamist revolution. Mali was all the proof anyone needed that Africa's nationalist leaders and their Western humanitarian backers were false prophets. The democracy held up by foreigners as an example to others was hollow, a narco state with a criminal kingpin in charge. And al-Qaida just happened to have a branch in northern Mali.

In early 2012, a group of low-ranking officers in the Malian army staged a mutiny to protest corruption in the upper ranks. To their surprise, Touré abruptly quit and flew to Senegal – tired, so diplomats said, of the endless squabbles inside his regime. Taking advantage of the confusion, in just three days in April, an alliance of Tuareg separatists and al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) seized the entire north of Mali, including the cities of Timbuktu, Gao and Kidal. A few months later, the Islamists turned on their Tuareg allies and kicked them out of the country. Suddenly, in the middle of the Sahara about an hour's flight south of Europe, there was a de-facto al-Qaida state the size of France.

The colonel predicted the Islamists would advance south towards Bamako within months and, on January 7 2013, convoys of AQIM fighters duly moved out of Timbuktu and, meeting no resistance, seemed to be heading for the capital. France had spent a fruitless year trying to marshal the creation of a West African intervention force to push back the Islamists. With Mali's takeover by al-Qaida apparently imminent, Paris acted. French warplanes were bombing the Islamists within days.

A key Islamist leader was Amadou Kouffa, a famous former marabout singer. Mali's marabouts wander from village to village reciting Islamic verses and performing folk music, precisely the kind of homespun departure from the Koran that a doctrinaire jihadi would consider heresy. So what had driven an artist into the austerity of fundamentalism?

Kouffa came from a village outside Sevaré, also called Kouffa. In Sevaré I found one of his neighbours, a 35-year-old livestock trader called Niama Tutu. Kouffa was a good story-teller, said Tutu, and well-respected. He also ran a small school. But as he entered his fifties, said Tutu, he began to change. His songs took on a political tone, decrying state corruption and brutality, especially the cocaine trade. One day in 2007 in Sevaré there was a conference of the Dawat-e-Islami, a conservative Islamic movement headquartered in Karachi. Kouffa attended and asked its organisers for their assistance in his campaign against the government. Perhaps inevitably, Kouffa began proposing Islamic revolution as the only solution to the criminality of the Malian state.

When the Islamists of AQIM and their Tuareg allies swept Mali's north, Kouffa evidently decided that the day of salvation he had long predicted had finally arrived. He moved to Timbuktu and joined AQIM's Islamic police. But this was not the great liberation of which Kouffa had spoken. The Islamic police spent their days closing down Timbuktu's tourist bars and nightclubs, forbidding women from leaving their homes, children from playing and smashing Timbuktu's centuries-old Sufi tombs.

If their totalitarianism wasn't bad enough, the Islamists also turned out to be as deeply criminal as the Malian state. A string of arrests and prosecutions around the world over the past decade have revealed how the Lebanese Shia militia, Hezbollah, has earned hundreds of millions of dollars from cocaine trafficking in West Africa, using the Lebanese expat community as cover. Taking their cue from Hezbollah, the Sunni AQIM soon began muscling in on the cocaine trade further inland. In the first decade of the new millennium, AQIM had made between $40m and $65m kidnapping and ransoming tourists in Mali and Niger. But as tourist numbers dwindled, they switched to escorting cocaine convoys across the Sahara.

It was the money the Islamists earned from crime that set conditions for the nightmare that followed the fall of Muammar Qaddafi in Libya in October 2011. Tens of thousands of Qaddafi's men, many of them ethnic Tuaregs from Mali and Niger, fled south into the Sahara.

With them they took millions of dollars in cash – enough to fill a truck, according to witnesses – and weapons including armoured vehicles, artillery, surface-to-air missiles, grenade launchers and thousands of AK-47s. In Mali and Niger they met willing and flush buyers for this arsenal in AQIM and several other Islamist and Tuareg groups. Six months later, these groups used their new firepower to attack the Malian army, easily overwhelming them and expelling them from the north of the country.

The Islamists' involvement in crime was a perfect hypocrisy. By combining the self-righteousness of the aid they detested with the despotism of the African tyrants they denounced, they might have been purposely setting up their revolution for popular failure. Sure enough, with no public support, their rebellion collapsed within days of France's attack.

But for Mali's Western backers, the intricate cause-and-effect of this disaster were just as damning. The same Malian government to which the West gave hundreds of millions of dollars and which the US was training in counter-terrorism had been business partners with an al-Qaida group that kidnapped and ransomed Westerners and smuggled billions of dollars of cocaine to Europe. The Islamists had then used their earnings to buy Gaddafi's guns and briefly create a terrorist state. After the 2013 war, Mali's foreign supporters carried on as if nothing had happened. Foreign aid grew to new heights when donors pledged $4bn to a new government led by a 78-year-old career politician, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. The French made no attempt to stop the cocaine convoys.

COCAINE NIGHTS

Not all foreign interventions in West Africa have been as disastrous as Mali. Around 9am on April 2nd, 2013, a sleek motor launch dropped anchor just off the sandy beach at the river port of Cacheu in northern Guinea-Bissau

Five men boarded, led by Rear Admiral Jose Americo Bubo Na Tchuto, chief of Guinea-Bissau's boat-less navy and a key power-broker for decades in Guinea-Bissau. The other men included two of Bubo's aides, Papis Djeme and Tchamy Yala, a fourth man the others knew as "Pedro," and a boat pilot. "I have some business friends and they want to invest in Guinea-Bissau," Admiral Bubo had told his men. "Most of them come in planes.

Some come in boats. These people are in the water and sailing to Bissau. We will take this small boat and go talk to them." The pilot guided the boat through the shallows of the Cacheu River and out into the open sea. Pedro, who had a satellite phone, dialled a number, asked for coordinates and was told to keep sailing south.

Around 2pm a large cargo vessel appeared on the horizon. The launch pulled alongside. There was a shout. Fifty men in black and dark blue uniforms were on the deck, levelling machine guns at them. The five men lay down, allowed themselves to be handcuffed and blindfolded, and were then marched onto the freighter.

The US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) had been working on the sting for more than a year. This May in New York, Bubo pleaded guilty to drug trafficking. His sentence and whereabouts were kept secret under the terms of a plea bargain. In September, Djeme was jailed for six and a half years. Yala is still awaiting his sentencing. Bubo's capture panicked Guinea-Bissau's other big smuggler, General Antonio Indjai. After Bubo's arrest, according to associates, Indjai's paranoia hit new heights when a new civilian President, Jose Mario Vaz, sacked him as army chief of staff this September. The general abruptly retreated to his chicken farm, taking with him around 1,000 soldiers from his own Balanta tribe.

The reality is Indjai has little reason to worry. Other than Bubo's seizure, the DEA has recorded just one other success against West Africa's cocaine trade. Europe, for whom the cocaine is ultimately destined, is yet to mount a single anti-trafficking operation in West Africa.

As the continent's economies and populations grow – from 1.2 billion now to 2.4 billion by 2050, by when around one in three people aged 10-24 in the world will be African – the continent is also becoming a drug retail destination in its own right. The UN estimates the number of crack and heroin users in West Africa at 1.6m and growing.

By failing to connect aid with fighting crime, of course, donors may also be fuelling the sort of popular frustration that, as in Mali, leads directly to Islamic revolution. One day in Bissau-City, I was having lunch with an acquaintance when he answered his phone by saying: "Ah! My Taliban friend." I asked for an introduction and sure enough, Sheikh Mohamed Aziz arrived at my hotel room looking uncannily like an African Osama bin Laden.

The Sheikh was convinced a revolution was imminent. "I'm optimistic," he said. "If one group oppresses others in their own interests, you can be sure that this group's days are limited. The corruption is too much. The lies are too much. This selfishness is getting worse every day."

The Sheikh whooped and clapped his hands at the prospect of West Africa's next Islamic upheaval. "This time is victory time for Islam," he said.

The full version of this article is published as part of the Newsweek Insights series currently available here for just 99p.