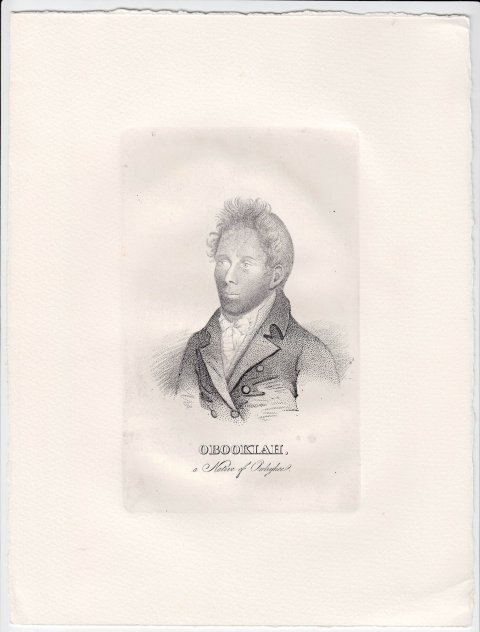

In the fall of 1809, a young man with dark skin and tattered clothes stood at the gates of Yale College, weeping. Crowds of students passed by until someone finally asked him what was wrong. He replied, in broken English, "that nobody gives me learning."

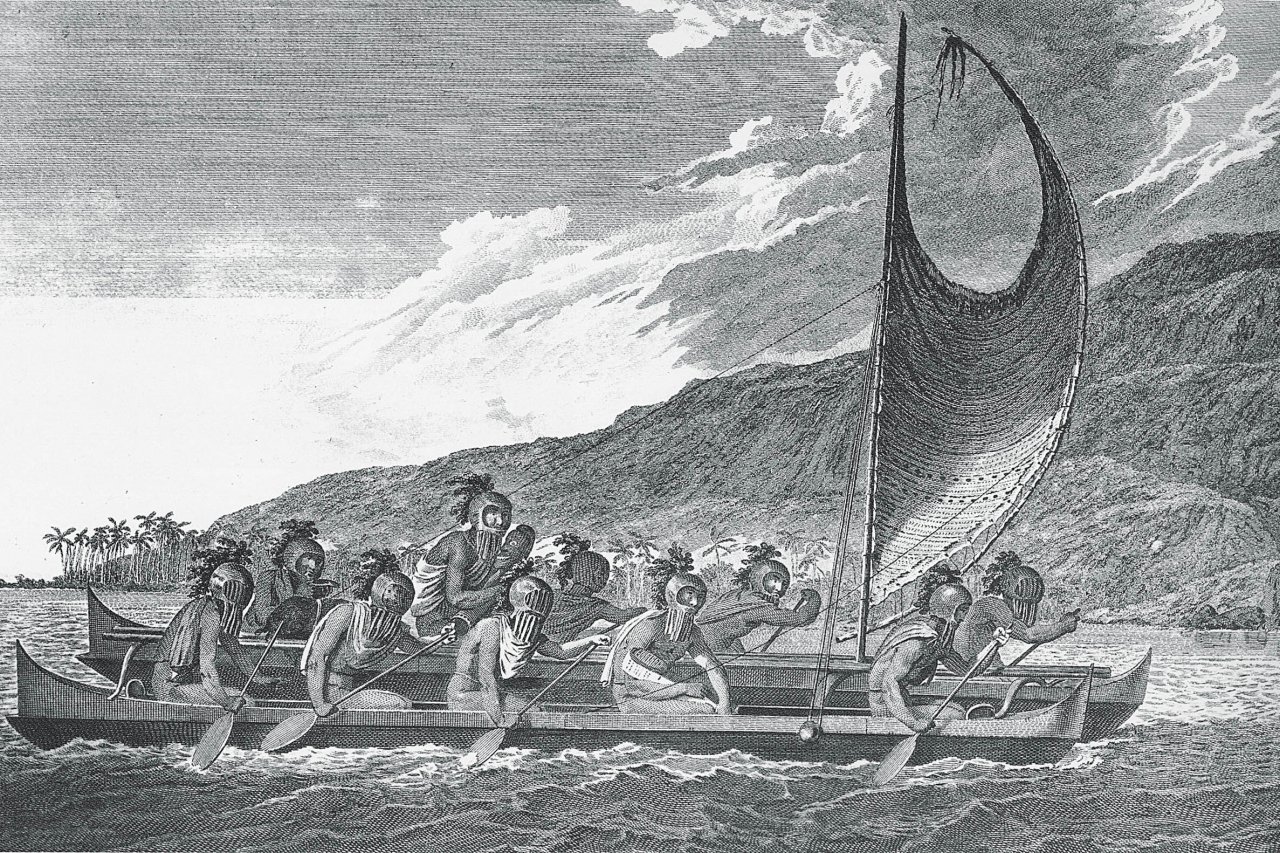

The young man, Henry Obookiah, was a most unlikely student to find his way to New Haven, Connecticut. Born in Hawaii in 1787, he was taken captive by the man who murdered his parents during a war among rival tribes on the island. He later negotiated his own release, moved in with an uncle and became an apprentice priest. Growing restless, he finagled his way onto a China Trade ship heading to the Northwest Coast (what's now Alaska), with hopes of one day making it to America. The boat sailed to China, then on to New York.

From there, Obookiah followed his captain to New Haven. He was around 22 at the time, and spent the next eight years living with at least a dozen families in eight towns across three New England states. Some of these people taught him English, but he wanted something more: a formal education. That's why he wound up standing in front of Yale's gates, and soon after, students started tutoring him. He lived for a time with the college's president. And that's how Obookiah, that weeping young man who yearned for "learning," met the people he needed to meet to become one of the inaugural scholars at a fledgling institution in Cornwall, Connecticut, known locally as the "heathen school."

Historian John Demos explores the dramatic rise and fall of the Foreign Mission School, as it was officially called, in The Heathen School: A Story of Hope and Betrayal in the Age of the Early Republic. Long-listed for the 2014 National Book Award, the book is about a group of esteemed Protestant missionaries in the early decades of the 19th century who recruited boys and young men from Hawaii, India, China and Native American nations to study in Cornwall. The school's aim was nothing less than the redemptive mission this country was built on. As Demos writes, "Our national traditions have fostered a generous spirit of outreach toward neighboring peoples and nations, a feeling of obligation…to make the world as a whole a better place." And so the "heathen school" would "civilize" its students, convert them to Christianity, educate them and then send them back to their homelands as missionaries and teachers.

The Heathen School is a story of devout Americans with a bloated sense of identity and purpose, striving to save the world. It's also about Native Americans holding on to their traditions while navigating racial prejudices and fighting for rights that were quickly being stripped away. And, like most of Demos's books, it all started with an anecdote so slight that most writers would have glossed over it.

'Just a piece of local history'

In the summer of 1996, Demos and his wife attended a dinner party in Cornwall. A guest started telling a story—"just a piece of local history," the man said—about a "heathen school" for boys and young men from around the world. After early success came disaster, he said: Two of the "heathens" fell in love with local women. The school was shunned, but both couples married anyway. The story ends years later, with the two "heathen" husbands, now leaders of the Cherokee Nation, paving the way for the genocidal Trail of Tears. And then a gruesome coda: cold-blooded murder.

Demos began researching the very next morning.

The Samuel Knight Professor Emeritus of History at Yale University, Demos has published numerous works on Colonial America, including the Bancroft Prize-winning Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England, which came out in 1982 and remains a major contribution to our understanding of witchcraft in the 17th century. His 1994 book, The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story From Early America, was a finalist for the 1994 National Book Award. Unlike many historians, Demos is determined to tell a riveting story. He writes with the lyricism and nuance of a novelist, which is why his books often reach the shelves of general readers, not just fellow historians.

With the heathen school, Demos knew he had a mesmerizing story, but after a few years of research he gave up on the book. Twice. "I was absolutely out of sympathy with the main characters—the missionaries and ministers who founded the school. I could not at all approve of their project, and more than that, they seemed to me incredibly smug," he says. Over the years, his feelings softened, and he picked up the "heathen book" again.

In May 1817, the Foreign Mission School opened its doors to a dozen young men—seven from Hawaii (including Obookiah), two from India, two from New England and one Native American. The young scholars lived in a two-story, wood-framed boarding house and studied in a modest schoolhouse on the green at the center of town. The principal lived nearby, and trusted locals, including two ministers, took on advisory and teaching roles. The students' days were rigorously scheduled. They attended classes for three hours in the morning and three hours in the afternoon, studying English, geography, arithmetic and rhetoric, among other subjects. They were also required to work in the school's fields two and a half days a week, and forbidden from visiting the homes or stores in town. Though cordoned off from Cornwall life, the "heathen youth" were expected to give public "examinations" in front of teachers, sponsors and locals, where they would recite lessons, pray, speak and perform in ways that showed just how civilized they had become.

Obookiah was the darling of the school. He learned English, converted to Christianity and attracted a loyal following from over a dozen states. With his transformation came donations of all kinds—cash and garden vegetables; quills, straw hats and pantaloons. In early 1818, nearly a year after the school officially opened, Obookiah caught typhus and died. The school's growing community of supporters erected an elaborate monument over his grave in the Cornwall cemetery, and poems honoring the young scholar appeared in newspapers. The Memoirs of Henry Obookiah, ghostwritten by Edwin Dwight, one of his Yale teachers, became a best-seller. And while community mourned the loss of its flourishing young student, his death brought with it hundreds of donations to the school.

Obookiah was their beacon of redemption—the proof that, as one "friend to the school" wrote, "heathen youth can be civilized, and instructed, and prepared for extensive usefulness among their countrymen…. No effort in behalf of the heathen world…has…resulted in greater benefit."

'The Perfect Cover-Up'

Despite its early public success, however, the Foreign Mission School was quietly unraveling. Students came and went. Many young men struggled to master English and grew homesick. "Discontent" and "indiscipline" rose through the ranks, writes Demos, quoting primary source materials. Some committed "the sin of drunkenness." Others returned to their homelands and promptly forgot all they had learned. Of the 50 students who passed through the heathen school in its first five years, just 16 completed all of the courses. Not even two of the school's greatest success stories could save it from failure. As the Hartford Courant wrote many years later, "[A]mong all who came to the school from strange lands, the little heathen Cupid, entering uninvited, was the mischief-maker."

John Ridge and his cousin, Elias Boudinot, came from an elite Cherokee family. Both were leading scholars at the school, and both fell in love with local women. In 1824, Ridge married Sarah Northrup, whose father was the school's steward and whose prominent extended family helped found both New Haven and Milford, Connecticut. Two years later, Boudinot married the beautiful Harriet Gold, whose parents were also involved in the school's mission.

Both marriages shocked the white families of Cornwall as well as many of the school's allies. Some claimed Northrup "ought to be publicly whipped, the Indian hung, and the mother drown'd," and the Mission School's governing board called Gold and Boudinot's union "criminal." One evening, townspeople gathered in front of the house Gold was staying in and hoisted up two paintings, one of a beautiful young white woman, the other of a Native American man. As church bells rang, the crowd unveiled two effigies meant to represent the two people in the paintings: Gold and Boudinot. Gold's brother then torched the effigies.

Intermarriage was the final blow. The school closed in 1826. "I think it was a doomed project from the start," Demos says. "With the big crisis of these marriages across racial lines, [the people at the school] were kind of relieved, because now they had a reason to close without having to admit that the whole plan was misconceived from the start. It was the perfect cover-up."

Demos follows both couples back to the Cherokee Nation in Georgia, where Ridge became an outspoken advocate for Native American rights and Boudinot became the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, the major Native American newspaper. The two budding leaders entered the political fray just as white Americans sought to force Cherokees off their land in Georgia. Both young men initially opposed this "Indian removal," but they faced growing pressure about relocation from President Andrew Jackson, Congress and white Georgians. A year after taking office, Jackson, who had a bloody military record as an "Indian killer," signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, granting him the power to negotiate deals with tribes. Those who acquiesced and moved west did so relatively peacefully; those who resisted were forced off their land.

Ridge, as a representative of the Cherokee Nation, met with Jackson to discuss removal. He left the conversation "convinced that the only alternative to save his people from moral and physical death was to make the best terms they could with the government, and remove out of the limits of the States." Controversial as it was among Native Americans, he, his father, Boudinot and a minority political party within the Cherokee Nation began advocating for removal. In 1835, Ridge's father, Cherokee leader Major Ridge, signed the Treaty of New Echota in Boudinot's living room. "I have signed my death warrant," Major Ridge reportedly declared. A few weeks later, his son hesitantly signed the document. Boudinot dreaded the moment as well: "I know that I take my life in my hand.… But Oh! What is a man worth who will not dare to die for his people?"

Rival Cherokee Nation leaders disputed the validity of the treaty, but the stage had already been set for the Trail of Tears, as the Cherokees described their disease-, hunger- and death-riddled forced exodus from Georgia to what's now Oklahoma. Then came the final violent act, at least within the confines of The Heathen School story: On June 22, 1839, Ridge and Boudinot were brutally murdered by members of the opposing Cherokee political group. Twenty-five men surrounded Ridge's farm on the borders of what's now Arkansas, Missouri and Oklahoma. He was dragged outside and stabbed to death as his wife and children watched. Boudinot, who was living about 50 miles south, was stabbed in the back and hit in the head with a hatchet near his home. Ridge and Boudinot's assassins had all the justification they needed to commit these gruesome acts: the nation's so-called Blood Law, which stated that any Cherokee who "dispose[d] of any lands belonging to this nation without special permission from the national authorities, he or they shall suffer death."

The Heathen School is a story of hope and betrayal, as its subtitle suggests, but it's also about white America's arrogant assumptions that it could "civilize" these "heathens." By the end of the book, a dark question lingers: Who, really, were the heathens, and who needed civilizing? Demos says the question he is asked most often at book readings is, What can we learn from The Heathen School that applies today? "The obvious answer is the hubris of overreaching," he says. "I think the Iraq War, as we look back on it now, is a glaring example of overreach. The Mission School 200 years ago is a microcosm of that same process."