"Mazi jaan, wake up. These men want to talk with you."

A man rolls over in bed. He is shirtless, and as he lifts his head and his eyes flutter open, he sees his 83-year-old mother standing in the doorway. She looks terrified. A stranger looms behind her. "Get up, sir, and get dressed," he says sternly. "We are here now."

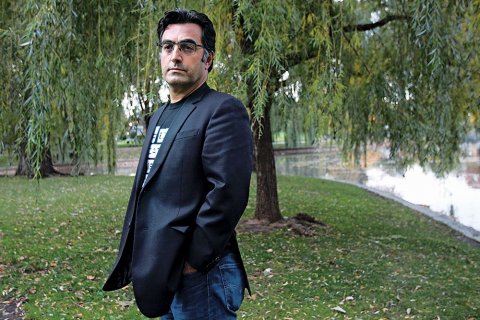

And so begins Rosewater, the movie about journalist and filmmaker Maziar Bahari's 118-day imprisonment following the controversial 2009 Iranian elections. Bahari, who was born in Tehran, was a Newsweek correspondent when the Mahmoud Ahmadinejad regime whisked him from his childhood home in broad daylight. Daily Show anchor Jon Stewart took a hiatus from his show last summer to write and direct the film, based on Bahari's best-selling book, Then They Came for Me, which takes us inside the tortuous, emotionally wrenching story of Bahari's incarceration, the beatings and interrogations, and his fight for freedom.

Rosewater may seem like a gigantic leap for Stewart, who is better known for his biting comedy, highbrow media criticism and hilarious feuds with conservative nemeses Bill O'Reilly and Sean Hannity. But Stewart and Bahari's worlds collided just days before Bahari was arrested, when he appeared on The Daily Show in one of Jason Jones's mock field reports from Tehran. After interviewing Bahari in a local coffee shop, Jones, wearing a keffiyeh and acting like an ignorant, bumbling American, scoffed, "Enough of his Western-educated, Newsweek doublespeak!" A few days later, Bahari was in Iran's infamous Evin Prison, where his captors showed him the clip—proof, they said, that he was an American spy.

In June 2009, Maziar, played as an endearing intellectual by Gael García Bernal, arrives in Tehran to cover the elections for Newsweek. "It's just one week," he tells his pregnant fiancée (now wife), Paola Gourley (Claire Foy), before leaving their home in London for the trip. We follow Bahari, then 42, to Tehran, where we see glimpses of the revolution as he makes his way through the politically charged city to report his story. He interviews President Ahmadinejad's main challenger, opposition leader Mir-Hossein Mousavi, then goes to the rooftop of an apartment building where young people who call themselves "The Educated" have secretly installed satellite dishes. "Welcome to Dish University," says one young man, proving that the government's oppressive grip hasn't won them over. Stewart also re-creates Bahari's fateful Daily Show interview.

The scenes fly by quickly, highlighting the city's mounting chaos, until we land in the middle of a massive demonstration in the streets. Mousavi supporters are peacefully protesting Ahmadinejad's suspicious victory. Then violence breaks out. Cracks of gunfire blast through the air as basijis, volunteer members of the Revolutionary Guard, start shooting at a group of protesters. Bahari is familiar with revolution and its murky, often violent backwash; his father was imprisoned by the Shah in the 1950s, his sister by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in the 1980s. Bahari raises his camera anyway and captures one man's death on film, knowing all too well the potential consequences.

Days later, men from the Revolutionary Guard are searching his childhood bedroom, looking for evidence of depravity and other kinds of wrongdoing. They take him to Evin Prison, where he is accused of spying for pretty much everyone—the CIA, MI6, Mossad, Newsweek—and dumped into solitary confinement. He spends his days in a claustrophobic white box with torn carpets. Spread across the walls are the hopeless etchings of past inmates: My God, have mercy on me, reads one. Another: Please, God, help me.

Bahari is given food teeming with bugs. He's blindfolded. Spat on. Emotionally abused and beaten. Throughout his incarceration, he talks to his dead father and sister, turning to them for guidance and support. As fantastical as these scenes may be, Bernal plays them believably, giving us insight into the emotional anguish Bahari endures as he vacillates between resilience and fear, sanity and agonizing madness. Is his mother safe? Does Gourley know he's alive? Will he see her again? What about their unborn child? Will he ever be free?

The crux of the film focuses on Bahari and his interrogator, whom he calls Rosewater because of the way he smells—like the mix of rosewater and sweat he smelled at a shrine when he was a boy. Danish actor Kim Bodnia plays Rosewater as a terrifying—and terrifyingly human—tormentor. One moment he's hammering Bahari's face against a desk. In another, he's lovingly chatting with his wife on the phone. Later, he's dragging a blindfolded Bahari down a hallway, toward yet another uncertain punishment.

Related: Read the Reporting Behind "Rosewater"

For a story rife with trauma and torture, Stewart's humor is never far away, although the jokes are restrained. "What is this?" Rosewater asks Bahari, holding a DVD of The Sopranos. "Porno," Rosewater adds, answering his own question. The art-house film Teorema? Porno! Leonard Cohen? Jewish! Porno! Bahari protests each time, until Rosewater holds up a magazine with Megan Fox on the cover. Porno? "Yes, could be," Bahari says.

Rosewater's obsession with New Jersey and his almost pitiful fascination with Western sexual mores both get big laughs. Stewart even plays to media insiders. "The American government doesn't control Newsweek magazine," Bahari tells Rosewater. "To be honest, it's not even worth controlling anymore." (A year later, in 2010, the Washington Post Company sold the magazine to Sidney Harman for a dollar.)

"The humor comes from the memoir, from Maziar's ability to observe the absurdity that was going on around him," Stewart explains. "The humor had to come organically. The biggest decision was not to heighten it."

The need for a break in the tension is sometimes so great that audiences will find themselves chuckling at even the slightest riff. It's not that film barrages you with endless scenes of gut-wrenching, bloody torture. It is rarely ever shown, and that's by design. "I did not want the audience to become numb to the torture porn we've become accustomed to seeing," Stewart explains. "I didn't want them to be able to escape."

Yet Another Beating

Aside from a few scenes in which hashtags, Twitter handles and headlines fly across the screen, Rosewater tells us very little about the international media campaign waged by Newsweek, Gourley, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Stewart and many others to free Bahari. The film focuses almost exclusively on his experience inside Evin, and keeping audiences in the dark about what was going outside the prison reminds them how little Bahari knew during those dreadful 118 days.

"I got the email from Maziar's nephew on a Sunday morning. It was Father's Day," recalls Nisid Hajari, who was Newsweek's foreign editor when Bahari was taken. "I woke up and checked my BlackBerry and saw the email that Maziar had been arrested. My wife recalls that I literally leapt out of bed to the desk in our hotel in one bound, screaming, 'Fuck fuck fuck fuck!'"

Bahari had given his editors an email list of friends and contacts, to be used if something happened to him in Tehran. Hajari says he sent a message to that group, asking them to hold off doing anything until the magazine could coordinate its initial response. "Everyone was great from that moment on, letting us take the lead and contributing," he recalls.

Hajari put his editorial duties on hold and spent four months working with colleagues to free Bahari. Lawyers and diplomats urged Newsweek to focus its efforts behind the scenes, although activists argued that quiet pressure wouldn't get anywhere. "Over time, we came to that conclusion as well," Hajari says. "We had our own internal legal team, and we also hired a Washington, D.C., firm that had diplomatic and governmental contacts. We hired a lawyer in Tehran as well."

Newsweek placed numerous op-eds in The New York Times, including one by then-Editor-in-Chief Jon Meacham. It leveraged the company's deep pockets and thick Rolodex, sharing Bahari's story with anyone who would listen.

Eventually, Clinton got involved. Gourley started giving interviews. She and Hajari spoke daily. Her pregnancy, he says, was a key part of the media campaign. "I called up a contact at the Iranian mission at the U.N. and said, in not so many words, if anything happened to her and the baby, we would hold them publicly responsible for this. It's a weird thing, but the image of a pregnant woman, a child, that meant something."

Hajari was tailgating with his father-in-law at a University of New Hampshire football game when he learned that Bahari had called Gourley from prison. That phone call is one of the most poignant scenes in the film. After threatening Bahari with yet another beating, Rosewater orders him to call his fiancée and warn her and Newsweek to back off their media campaigns. Suddenly, Bahari finds himself dialing. He hears the steady ring ring, ring ring, followed by the one voice he's been yearning for since he was taken. It's Gourley, and she's telling him they're having a baby girl. Bahari lurches into uncontrollable, joyous laughter. Furious, Rosewater beats him. Bahari keeps on laughing.

The phone call marks a turning point in Bahari's captivity. As Stewart puts it, "That scene to me was the fulcrum of the entire movie, where the transformation from Maziar's victimhood to victory is sealed, where he takes back his power in a non-oppositional way. He takes it back through laughter." It was also one of the first scenes he filmed.

As soon as Newsweek learned about the call, "we ramped things up," Hajari says. "The costs of keeping Maziar were higher than the costs of letting him go, and that was the whole strategy all along."

On October 17, 2009, 118 days, 12 hours and 54 minutes after being taken, Bahari was released on $300,000 bail. A week later, back in London, he was with Gourley as she gave birth to a baby girl.

'I'm a Giant Asshole'

"In prison, I promised myself that one day I'd come out and tell this story to the rest of the world," Bahari says. "And this story was my story, of course, and also the story of many journalists imprisoned in Iran—and many going through the same experience all around the world, every day."

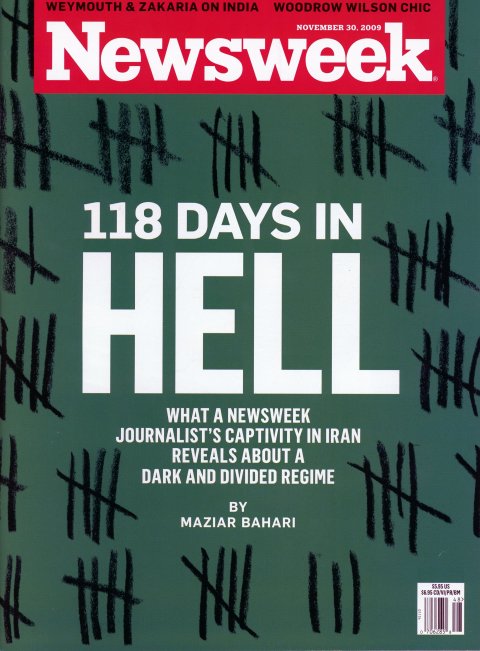

Upon his return, Bahari wrote a cover story for Newsweek, "118 Days in Hell." "We said, 'If you feel like writing it and getting it out there, just pour it out. Don't worry about a lede and kicker and nut graf," recalls Hajari, who edited the piece with then-Newsweek editor Christopher Dickey. When Bahari filed his story, it was tens of thousands of words long.

Bahari also became a frequent guest on The Daily Show. His friendship with Stewart took off, and the two men started collaborating on the movie, working side by side throughout filming. Asked what it was like consulting with Bahari on the torture scenes, Stewart goes into one of his familiar storytelling monologues:

"Was that where he hit you? Were you down on the ground?"

"No, I was on the chair. He'd hit me just a little in the back of the head."

"Oh my God, I'm a giant asshole, I can't believe I just [asked] that."

To Bahari, Stewart's questions were simply part of the job. "As journalists we are used to putting a distance between ourselves and the subject," he says. "This was another journalistic work.… That was on a rational level, of course. On an emotional level, it was much more difficult," he adds, "because there are so many journalists all around the world who are being persecuted…. It doesn't matter if you are American or [from an] anti-ally government; I think about their wives, sisters, children." During filming, the only scenes Bahari didn't watch were the ones centered on his mother and sister.

Bahari's daughter is now 5, and aside from a vague awareness that "Daddy sometimes goes on television, and Daddy is friends with Jon Stewart," she knows very little about her father's past. "I will tell her the truth, and I will tell her whenever I think she's ready," Bahari says.

Whenever that is, Bahari's book and Stewart's film reveal the agonizing ordeal her father, and so many journalists like him, have endured at the hands of corrupt regimes. "I'm one of the lucky ones who had an international profile," Bahari says. "I had an amazing company in the Washington Post Company that really signed the blank check and said, 'We have to get Maziar out of prison any way we can.' Many colleagues don't have international profiles. People don't know their names. They are statistics. I have this public profile now, and I have to use it for others."