Today, even the people most intimately involved with the events of June 9, 2006, can hardly remember the names of the men who died that night. In the official literature, they are often referred to by their Internment Serial Numbers, the prevailing nomenclature of the Guantánamo Bay detention center: 588, 093 and 693. But before they were numbers, they were people. All thought of themselves as Allah's fervent disciple, only to end up American prisoners of war, stashed away on the forlorn edge of Communist Cuba.

The three men had recently ended a hunger strike. They had little else in common.

Mana Shaman Allabardi al-Tabi (588) was a Saudi national who joined a religious charity called Tablighi Jamaat, which was believed to have links to Al-Qaeda. On January 17, 2002, "detainee was captured with four other individuals who were dressed in burkas trying to avoid capture" as he was leaving the Pakistani city of Bannu, on the border with Afghanistan, his Department of Defense file reads. On March 8, 2002, he was handed over to American forces and shipped to Guantánamo Bay, where he was described as "belligerent, argumentative, harassing, and very aggressive"—and useless when it came to intelligence about Al-Qaeda. He was cleared to be "transferred to the control of another country for continued detention."

Yasser Talal al-Zahrani (093), also Saudi, was the son of a prominent government official. Jihad tugged at him in the early summer of 2001, when he had finished the 11th grade. "After sitting at home for approximately two months and hearing that sheiks from neighboring towns were saying jihad in Afghanistan was a religious duty, [al-Zahrani] decided to travel to Afghanistan," his Pentagon file says. He went to Pakistan, then Afghanistan. Instead of starting his senior year of high school, he learned at a Taliban training center how to use a Kalashnikov assault rifle and a Makarov pistol. He served as "a fighter on the front lines of [the Battle of Kunduz]" during the American invasion of Afghanistan, where he was captured by the Northern Alliance. Al-Zahrani was turned over to American forces on December 29, 2001. His intelligence value was also minimal.

Ali Abdullah Ahmed (693) was a Yemeni who, according to his Department of Defense record, was "a street vendor who sold clothing…and was prompted to travel to Pakistan to receive [a religious] education upon hearing God's calling." He was captured at a safe house in Faisalabad that was alleged to be under the control of Abu Zubaydah, then believed to be one of Osama bin Laden's top officers. Branded by the Pentagon as "a mid-to-high-level Al-Qaeda" operative, Ahmed arrived in Cuba on June 19, 2002. Later, government investigators realized there was "no credible information" tying him to terrorism. But this wasn't the Palookaville slammer: If you tell the world, as the Pentagon did, that your island prison is home to "the worst of the worst," you won't want to advertise your errors and hyperboles. So they kept Ahmed.

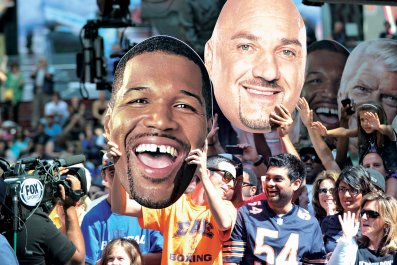

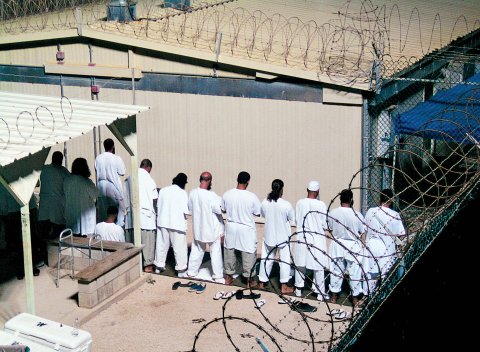

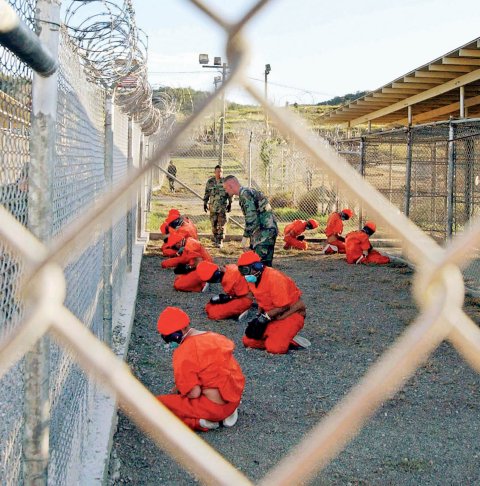

The night all three of them died, about 460 detainees were in American custody at Guantánamo Bay, most of them inconsequential actors in an international drama they hardly understood. Some thought America was the Great Satan; some probably couldn't find it on a map. Prisoners from the global War on Terror had first arrived on the southeastern shore of Cuba on January 11, 2002. They were housed in the cages of Camp X-Ray, whose barbed wire became, depending on whom you asked, symbols of America's might or its cruelty.

On April 28 of that year, Camp Delta opened on the easternmost edge of the camp, near the border with Cuba. It was separated by high, parched hills from the naval station, which had been leased by the United States since 1903. The detainees were housed in cell blocks atop cliffs that drop steeply toward the Caribbean Sea, with its alluring and infinite expanse.

Sergeant Joseph L. Hickman arrived at Camp Delta on March 10, 2006. He is a native of a tough south Baltimore neighborhood called Brooklyn who had joined the U.S. Marine Corps when he was 18. "It was there that I found my place in the world," he writes in his new book, which will be published later this month. Hickman left the Marines in 1987 for a job at a security firm, re-enlisting, with the Army this time, in 1994. He stayed for four years, then worked as a civilian in prison transport and executive security. In the wake of 9/11, he joined the Maryland National Guard and was assigned to the 629th Military Intelligence Battalion. Four months later, he was thrilled to learn of his unit's deployment to Guantánamo Bay: "Finally, at 41, I had my chance to meet the enemy."

He would meet that enemy in more intimate quarters than he probably imagined. On May 18, 2006, Hickman was part of a quick-reaction force (QRF) that responded to a supposed suicide in Camp 4, a section of Camp Delta where the detainees are housed communally in cells that hold 10 men. The suicide attempt was a ruse. The detainees had lathered the floor of the cell with soap and assailed the slip-sliding QRF with "a volley of piss, feces, and metal objects," including a pole from a dismantled fan. Despite the close confines, Hickman gave the order for one of his soldiers to fire an M203 grenade launcher, whose 40 millimeter rubber rounds were deemed "Evil SpongeBob" by some in the platoon. Hickman thus became, in his own estimation, the first American soldier to give the order to fire on detainees at Guantánamo Bay. Helped by blasts of pepper spray, Evil SpongeBob quelled the revolt, and Hickman was praised for his "exemplary leadership" in a commendation signed by Colonel Michael I. Bumgarner. Months later, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Rear Admiral Harry B. Harris Jr., then the commander of the base, remembered the "gutsy call" to fire on the detainees.

On June 9, a soldier floored by a cluster headache asked Hickman to stand in for him as the sergeant of the guard that evening. At 5:15 p.m., Hickman and his men showed up for duty, prepared to guard Camp Delta for the night. For the first hour of the shift, Hickman's position was at the primary entrance to Camp Delta, Sally Port 1. As evening prayers were starting in the cells, at about 6:30 p.m., Hickman went up to Tower 1, at the northern edge of Camp Delta.

Fifteen minutes later, he saw a white van enter Camp Delta and park at Alpha block. Hickman would later write that he witnessed escorts marching a detainee into the back of the van, which had no windows in its rear portion. He noticed they were using metal handcuffs, not the plastic flex cuffs that were standard issue at Camp Delta. Hickman told me the van returned about 20 minutes later and picked up a second detainee, driving away with him.

The van came back to Alpha block once more. "As they were loading the third detainee," Hickman recalls, "I went to [Access Control Point] Roosevelt ahead of them to see where they were going." ACP Roosevelt leads out of Camp America, into the sun-blasted hills that hide the detention center from the naval station, which looks a lot like a slightly rundown South Florida strip: McDonald's, bowling alley, ball fields. Hickman claims that the van turned left, heading down a road that led not to the naval station but a private beach for officers. He says the only other destination could have been what he calls in his book Camp No (as in no such place), a secretive facility outside the wire he had correctly surmised was a CIA "black site." (An Associated Press report much later confirmed that the site did exist: It was named Penny Lane, and its purpose was supposedly to turn detainees into CIA assets who could infiltrate jihadist networks.)

The white van returned to Alpha block at 11:30 p.m., heading for the detainee medical clinic. That, says Hickman in his book, is when "everything changed."

'Boo-Freakin'-Hoo'

"Three detainees being held at the United States military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, committed suicide early on Saturday, the first deaths of detainees to be reported at the military prison since it opened in early 2002," James Risen and Tim Golden of The New York Times reported from Washington in an article published June 11. Citing the military officials who controlled the drip of news out of Guantánamo Bay, Risen and Golden wrote that "the three hanged themselves in their cells with nooses made of sheets and clothing, and died before they could be revived by medical personnel." Twenty-five detainees had attempted suicide on 41 separate occasions since Guantánamo had opened. This trio, it seemed, had been the first to succeed.

Even today, it is impossible to independently confirm much of what goes on in this most remote and secretive of American outposts; information is a scarce commodity on "the island," as the base is universally known by its American denizens.

There were then four journalists on base in the wake of the June 9 deaths: one from the Los Angeles Times, one from The Miami Herald, and a reporter-photographer duo from The Charlotte Observer, there to profile Bumgarner, who is a North Carolina native. At the time, Bumgarner was commander of the Joint Detention Operations Group, "the warden of Guantánamo Bay," asThe New York Times Magazine would call him in a lengthy profile.Now, the journalists were told to leave.

The basis for that order appears to have been some intemperate statements Bumgarner made in the presence of Michael Gordon, the Observer reporter, in the wake of the deaths: "There is not a trustworthy son of a bitch in the entire bunch," he said of the camp's detainees. This was an outburst of frustration that smeared Bumgarner's own unflagging efforts to earn the detainees' trust. Still, he'd said those words, and Gordon published them.

But a more telling misstep by Bumgarner may have been revealing the potential cause of death of the three men. In an article published in the Observer on June 12, Gordon reported that "Bumgarner said each man had a large wad of cloth in his mouth. He said he did not know if the material was for choking [them] or to muffle their voices while they took their lives."

Two days later, Gordon, his photographer and the other two journalists were expelled. According to The New York Times, Gordon "may have obtained too many details about the military's response to the suicides, leading the Pentagon to impose new restrictions on reporters," though Department of Defense officials denied that that had been the reason. Bumgarner was suspended and investigated for his indiscretions. He was eventually absolved.

Much of what happens at Guantánamo, why it happens and who orders it to happen lurks in the shadowy realm of "unknown unknowns," in the famous formulation of former defense secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, even to the men and women stationed there. An order might have come from U.S. Southern Command, which has control over the base, or from the Pentagon, where Rumsfeld was keenly interested in the intelligence gleaned from detainees. Langley also had a stake in the interrogations there, with former CIA director Michael V. Hayden paying a visit to a Guantánamo Bay black site in late 2006.

It is a paradox of Guantánamo Bay that a military base so close to the American mainland lies so far outside the bounds of ascertainable fact. Some may even like it that way. To many Americans, Guantánamo was a necessity, one that should not have occasioned outrage: In 2005, only 20 percent of those polled said they believed the detainees there were treated unfairly, according to a Rasmussen Reports survey.

Some took the deaths as last gasps of desperation; others figured that these were only just deserts. Appearing on The O'Reilly Factor, right-wing provocateur Michelle Malkin suggested that the appropriate response to the suicides of these three prisoners was "boo-freakin'-hoo." Though usually not one for moderation, Bill O'Reilly struck a note of morbid sympathy: "If I were in Guantánamo Bay, and I couldn't get out—and these guys will never get out, believe me—I might commit suicide too."

'I Began Having Nightmares'

Hickman left Guantánamo Bay about nine months later, on March 10, 2007, having earned four awards or commendations while stationed in Cuba, including an Army Achievement Medal that praised his "dedication to duty and professionalism." He returned to Maryland and was assigned to an Air Cavalry brigade in Annapolis, where he was "responsible for training other guys going overseas."

One night, he came home to his apartment in Baltimore and turned on the evening news. He discovered, to his dismay, that there had been another suicide at Guantánamo Bay: A Saudi national named Abdul Rahman Ma'ath Thafir al-Amri was found hanging in his cell in Camp 5. Memories of Cuba, and what Hickman saw on June 9, flooded back. "For the next few weeks, I couldn't sleep," Hickman writes in his new book,Murder at Camp Delta: A Staff Sergeant's Pursuit of the Truth About Guantánamo Bay. "When I did finally shut my eyes, I began having nightmares."

He revisited, in detail, the last hours and minutes of June 9, 2006. Hickman does not, as far as I can tell, harbor much sympathy for the detainees. It is a feeling of betrayal that drives him, a disbelief that the military in which he spent three decades of his life could allow men in its care to die. Worse yet, that it might have killed them.

Hickman remains certain of what he saw. On the night of June 9, he claims that he had a clear view of the only path between Alpha block and the detainee medical clinic, where the dead or dying detainees would have been brought by Navy escorts. But as he writes of himself and his fellow guards, "We saw no detainees carried, dragged, walked, or hauled…into the clinic" that night. "Unless there was a secret tunnel, or Star Trek-type transporter unit hidden somewhere on the base, the only way those detainees could have arrived at the medical clinic was inside the white van," which he had clearly seen travel outside Camp America and in the apparent direction of Camp No.

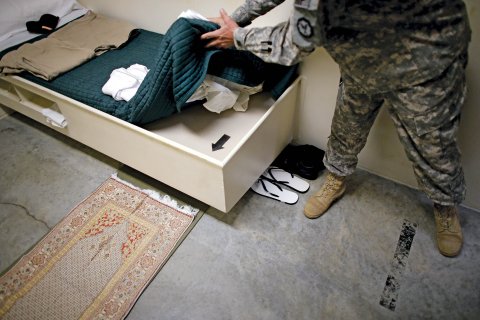

Hickman writes that there were fewer than 30 detainees in Alpha block (the exact number is hard to verify) housed in "six-by-eight-foot cells with walls made entirely of mesh" that were easy to see through. The five guards had to check the cells every three minutes, giving the detainees no time to coordinate and carry out a complicated plot to kill themselves simultaneously. Hickman also notes that all three detainees had recently concluded a lengthy hunger strike. "No one engaging in a hunger strike was ever given extra blankets or towels," he writes. (Indeed, when investigators interviewed an Alpha block detainee on the day after the suicides, he complained that "all the incentives were taken away from them.")

Hickman describes how around midnight, "the whole camp lit up like a football field under stadium lights." A guard was dispatched to convey a message of "code red" to a sailor, though neither he nor Hickman knew what "code red" meant. Perplexed, Hickman headed for the medical clinic. On his way, he ran into a Navy medic with whom he'd gone on several dates. She "looked really upset," Hickman writes, having just attended to the three dead men. "They had rags stuffed down their throats," he remembers her saying. "And one of them was badly bruised."

Military records give a sense of the harrowing scene that must have taken place in that clinic. They also confirm parts of Hickman's narrative. Ahmed's medical file says he died "by likely asphyxiation from obstructing his airway." He had, according to those present, "what appeared to be either gauze or white fabric lodged in the back of [his] mouth."

The morning after, Bumgarner called a 7 a.m. meeting for the 75 or so soldiers and sailors who'd been on duty in Camp 1 and elsewhere the previous night. According to Hickman, Bumgarner said the detainees "committed suicide by cutting up their bedsheets and stuffing them down their throats." He warned those gathered that they were "going to hear something different in the media," a discrepancy about which he allegedly ordered them to remain silent. (Bumgarner denies that, though seven people present that morning corroborated Hickman's account to researchers.)

Hickman writes in his book that as Bumgarner finished speaking, he "felt sick with shame...I knew the truth. My men knew the truth."

A Double Life

In 2008, Hickman was working as an Army recruiter in Green Bay, Wisconsin, "leading a sort of double life," he writes, conscripting young men and women into the military while harboring doubts about the scruples of some in the armed services.

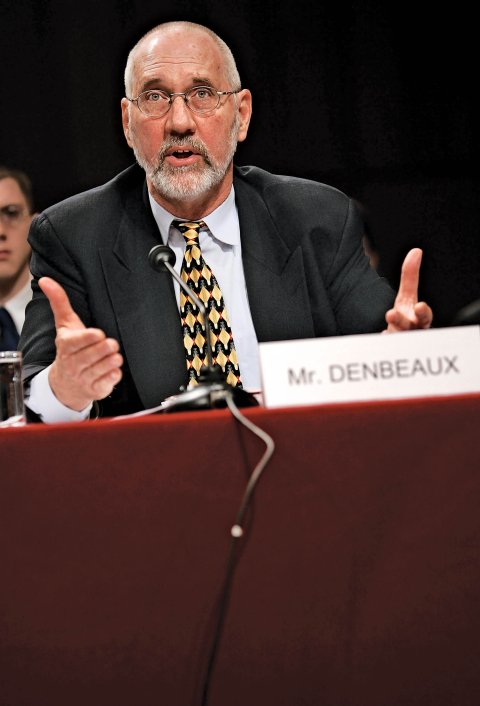

Hickman was desperate to tell his story, but wasn't ready to go to the media. An intriguing lifeline came in the form of Mark P. Denbeaux, a former radical running the Center for Policy and Research at the Seton Hall University School of Law in downtown Newark, New Jersey. Denbeaux's group had written a report in 2006 showing that, despite the assertions of the George W. Bush administration, only 8 percent of the detainees at Guantánamo Bay were members of Al-Qaeda, while 86 percent had been "arrested by either Pakistan or the Northern Alliance," and then essentially sold to American forces for about $5,000 each. Another report had focused on the June 9 affair; without yet calling into question what happened, the report blasted the government for the extra-legal purgatory in which it kept the three men and their fellow detainees.

A "lifelong conservative," Hickman was put off by Denbeaux's roots in 1960s radicalism, but he felt that the work being done at Seton Hall was "better informed and more objective than any work being done by reporters," who seemed to him uniformly eager to propagate the official Pentagon line. And so, on January 23, 2009, Hickman picked up the phone.

Impolitically Honest

"An old draft-dodger" is how Mark Denbeaux describes himself. With his imposing height and white beard, he could pass for a country preacher, too. As a student at a small college in Ohio, he joined the civil rights movement and traveled to Selma, Alabama, for the momentous march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge. After graduating from the New York University School of Law in 1968, he defended members of the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, as well as the so-called Mayflower Madam, Sydney Biddle Barrows. He also became an expert in discrediting the validity of expert handwriting testimony.

For the past nine years, Denbeaux has been consumed by the case of the detainees at Guantánamo Bay, whose identities, rights and alleged terrorist affiliations have all been the subject of speculation and rancor. Denbeaux and his students tried to fill the information gap with their reports, starting with a profile of 517 detainees compiled from Department of Defense data.

"First, I thought it was a lunatic calling me," Denbeaux says, reclining in the plain, windowless room that serves as the epicenter of Guantánamo research at Seton Hall. It looks like the well-used office of a high school newspaper, except for the photos of suspected terrorists and a scowling Dick Cheney. Denbeaux says he was in New York City at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, about to sit on a panel titled "Looking Beyond Reasonable Doubt: Evidentiary Standards From Christian Theology to Guantánamo," when Hickman called, claiming he had information about the June 9 deaths. Reporting on Guantánamo had exposed Denbeaux to plenty of conspiracy theorists, and he thought Hickman was just another member of the tinfoil-hat tribe. But unlike those forlorn souls, Hickman had actually been there.

They spoke after the Cardozo event. Two days later, Hickman was on an airplane headed for Newark.

At Seton Hall, Hickman met with Denbeaux and his son Joshua W. Denbeaux, who runs a law firm with his mother, Marcia. Father and son listened to Hickman but remained skeptical, pointing to a 1,700-page report by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), published in 2008, that definitively declared the three men had committed suicide. "I cannot believe that the authorities at Gitmo would fake a single suicide," Mark Denbeaux told Hickman, "let alone three. I don't believe in conspiracies."

Nevertheless, Denbeaux had his students print out the huge NCIS report, which had been redacted almost to the point of gibberish, its out-of-order pages frustrating anyone seeking to impose order on the material. Denbeaux wanted Hickman to stay out of his students' investigation. He had provided a tip, but they would follow it on their own.

In the winter of 2009, with Josh Denbeaux acting as his lawyer, Hickman took his allegations about the deaths to the Army Inspector General, whose office was nonplussed: "What am I supposed to do with this statement?" an official there wondered to Josh Denbeaux. After appearing bullish to investigate, Hickman writes, Teresa L. McHenry of the Department of Justice's (DOJ) Criminal Division backed off.

In response to my questions about why the DOJ decided not to delve deeper, Peter Carr, spokesman for the Criminal Division, sent me a statement that reaffirmed confidence in the "thorough" initial investigation by the military. He also noted that the DOJ and the FBI "reviewed new allegations made by one of the perimeter guards who had been on duty the evening of these individuals' deaths. During its review, the team interviewed a number of persons, examined large amounts of evidentiary material and traveled to Guantánamo Bay. The team ultimately concluded that there was no credible evidence to support the allegations."

By late 2009, Hickman had exhausted his legal options. But as chances of an official investigation diminished, Mark Denbeaux and his students published a 136-page report titled "Death in Camp Delta" that December. It does not mention Hickman, but it forcefully confirms his suspicions about how and where the men died.

For example, "Death in Camp Delta" notes that, based on autopsies, the detainees had been dead for at least two hours by the time they came under medical attention. That would have meant that not one of the five guards on duty noticed anything amiss (prisoners hanging in their cells, for example), though they were supposed to check on the detainees every three minutes. And if the guards had so thoroughly failed to carry out their responsibilities that night, the report asks, why weren't any of them reprimanded?

The report also points out that several Alpha block guards were "advised that they were suspected of making false statements" about what had happened that night. The contents of those original statements are unknown, but the Seton Hall report implies they hadn't been what the camp's commanders had in mind.

The purported "how" of the suicides was also called into question. In his book, Hickman writes that detainees had to have been "veritable Al-Qaeda Houdinis" to have killed themselves in the way the NCIS claims they did. Denbeaux and his students put the matter in a slightly bemused voice that is the hallmark of all their reports:

There is no explanation of how each of the detainees, much less all three, could have done the following: braided a noose by tearing up his sheets and/or clothing, made a mannequin of himself so it would appear to the guards he was asleep in his cell, hung sheets to block vision into the cell—a violation of Standard Operating Procedures, tied his feet together, tied his hands together, hung the noose from the metal mesh of the cell wall and/or ceiling, climbed up on to the sink, put the noose around his neck and released his weight to result in death by strangulation

The Seton Hall report was a measure of vindication for Hickman. But it wasn't enough.

The Missing Necks

Television was Hickman's next hope. In the summer of 2009, he took his story to Jim Miklaszewski, the national security correspondent for NBC News; ABC News investigative journalist Brian Ross; and CBS newsmagazine 60 Minutes. ABC appeared to be putting together a story, but according to Hickman, Ross's team said it "ran into some problems" with his account. (Hickman speculates that the Pentagon scared Ross off. Ross did not respond to my request for comment.)

Denbeaux had an idea. He knew an international human rights lawyer who was also an editor at Harper's Magazine: R. Scott Horton, whom Hickman calls "another liberal activist I never would have imagined having anything in common with." Horton met with him several times in Manhattan and also interviewed other guards who'd been on duty that night.

Horton's article, titled "The Guantánamo 'Suicides': A Camp Delta sergeant blows the whistle," ran in the March 2010 issue of Harper's. It relied heavily on Hickman's recollections and the work done by Denbeaux's students. It was the first article in a major American publication to argue that the three men had not hanged themselves.

Having examined the results of independent autopsies of the three detainees, Horton concluded that "the three men who died at Guantánamo showed signs of torture, including hemorrhages, needle marks and significant bruising." He also interviewed three soldiers on duty that night who corroborated Hickman's account, including one who "spoke to Navy guards who said the men had died as the result of having rags stuffed down their throats." The detainees' excised necks, Horton wrote, were never returned to the families after being examined by military pathologists.

Hickman connected the three detainees' plight to that of another detainee, a Saudi named Shaker Aamer who claimed to have been "the victim of an act of striking brutality" the same night as those deaths. His lawyer, Zachary P. Katznelson, described the torture Aamer allegedly experienced in a federal filing, which Horton excerpted at length: "On June 9th, 2006, [Aamer] was beaten for two and a half hours straight. Seven naval military police participated in his beating. Mr. Aamer stated he had refused to provide a retina scan and fingerprints. He reported to me that he was strapped to a chair, fully restrained at the head, arms and legs. The [military police] inflicted so much pain, Mr. Aamer said he thought he was going to die."

The filing by Katznelson also says that "they cut off his airway, then put a mask on him so he could not cry out." Horton wrote that this "is the same technique that appears to have been used on the three deceased prisoners," a reference to the rags that Bumgarner admitted had been pulled out of the detainees' throats.

Hickman told me that after Horton's article came out, he kept waiting for one of the Navy guards on duty that night to call him and chew him out, tell him how wrong he was and how little he knew.

No such call came.

In fact, as Hickman and Denbeaux continued to investigate, they unearthed several pieces of evidence from the military's documents that strengthened their case (those findings appear in a Seton Hall report from the spring of 2014 called "Uncovering the Cover Ups: Death in Camp Delta"). One of those statements was made by a guard who had worked on Alpha block earlier on June 9 (the exact times are redacted, but it appears to have been a morning-afternoon shift). "The shift I worked Block Guards conducted cell searches of all the cells on Alpha Block," the guard's statement reads. "We did not discover anything that a detainee could hang himself with. We did not find any weapons either. I heard rumors that the detainees bound their hands and feet and then hung themselves with altered sheets. I searched cell 5 but I did not find anything that would allow the detainee in cell 5 to hang himself in the manner of the rumors."

An even more troubling statement came from a Navy master-at-arms inadvertently identified, via the imperfect redaction of another document, as "Denny." Sometime in the very first minutes of June 10, Denny, who was part of an escort unit, was summoned to Camp 1 and informed that a detainee (identified as "093," or al-Zahrani) had been taken from Alpha block to the detainee clinic, in an apparent breach of protocol. "I was surprised to hear that the detainee was already in the clinic," Denny explains, "because he was not supposed to be moved from his cell without an escort team, for this reason I had a feeling something was wrong."

Al-Zahrani was still alive, yet Denny says that he "never saw any medical staff perform chest compressions on the detainee." Denny says the detainee was in handcuffs, supporting Hickman's assertion; "[a]fter the handcuffs were removed, I observed a corpsman wrapping an altered detainee sheet, that looked like the same material [al-Zahrani] used to hang himself, around the detainee's right wrist…. The cloth was not on the detainee's wrists when the Camp 1 guards removed the handcuffs a few minutes earlier." (Denny also notes that "Combat Camera personnel" showed up to film the scene, though video evidence from that night has never emerged.)

Denny says he was ordered to help transport al-Zahrani to the naval hospital, which is outside Camp America. In the ambulance, he and others started doing chest compressions on the detainee:

When I pulled [al-Zahrani's] head back again, the corpsman and I noticed that the detainee's neck was swollen, puffy and was a purple color. As the corpsman pushed on the detainee's neck, the corpsman seemed surprised to see that the detainee still had a piece of material wrapped tightly three or four times around his neck.

But as the Seton Hall group notes in its most recent report, a "medical responder" interviewed during the subsequent investigation said that "[t]here were no foreign objects around his neck." So why did Denny observe a noose coiled around his throat?

Al-Zahrani was taken to the naval hospital, where he was pronounced dead a little after midnight on June 10, 2006. He was 21.

'A Darker Possibility'

Today, Joe Hickman, now 50, lives in Green Bay. He says he is "very much a patriot," one who routinely volunteers with veterans' groups when he isn't helping the Seton Hall law school students with their Guantánamo reports. "It was therapeutic to write down everything that happened," he says of his book, which he began writing five years ago. If the Seton Hall report on Camp Delta was a seed, and Horton's article for Harper's a sapling, then Murder at Camp Delta is the tree in full bloom, its branches reaching into the spooky shadows of the national security apparatus.

Calling his book "a matter of honor," he continues to seek a reinvestigation of the detainee deaths with a tenacity that might make his old Marine drill instructors proud. But while he is sure about what happened, answers to the questions of who and why remain elusive. To even try to answer them is to enter a terrain where every assertion starts to sound like a plotline from Homeland.

And those questions are corollaries of a bigger one: What was the purpose of Guantánamo? While the Bush administration pitched the place to the American public as a detention center, some of those who worked there grasped that it had another, more nefarious function. Among the early skeptics was Colonel Brittain P. Mallow, who headed the Army's Criminal Investigation Task Force, which was charged with building legal cases against Guantánamo detainees. As he wrote in 2006 to Michigan Senator Carl M. Levin of the Senate Armed Services Committee, under the command of Major General Michael B. Dunleavy and then Major General Geoffrey D. Miller, Guantánamo became a "battle lab." Mallow wrote to Levin that "interrogations and other procedures there were to some degree experimental, and their lessons, would benefit [the DOD] in other places." If the prison was an experiment, then the detainees were its helpless subjects, waiting in their cages to see what the interrogators would try next. Loud music? Perfume? Photos of 9/11 victims?

Some of this testing appears to have been subtle, performed under the guise of medical care for the detainees. For example, one of the reports written by Denbeaux and his students notes that all detainees at Guantánamo Bay were administered 1,250 milligrams of the antimalarial drug mefloquine upon arrival in Cuba. The dosage, given in two parts, is plainly visible on the medical records of two detainees, which are included in the Seton Hall report. But that would be a "massive overdose," Dr. Remington L. Nevin of Johns Hopkins University, who was a major in the Army and has extensively studied mefloquine's effects, told Hickman in a phone conversation. Dr. Nevin told me that there had been "worrisome misue" of the drug at Guantánamo Bay and that its application merited a formal investigation. After all, Cuba had been declared a malaria-free country by the World Health Organization in 1973, calling into question why mefloquine was administered at all.

Maybe malaria was only an excuse. The Seton Hall group wrote in the 2010 report that mefloquine can cause "severe neuropsychological adverse effects," including anxiety, hallucination and suicidal ideation. The drug wasn't just unnecessary; it was dangerous. The report continues, "This suggests a darker possibility: that the military gave detainees the drug specifically to bring about the adverse side effects, either as part of enhanced interrogation techniques, experimentation in behavioral modification, or torture for some other purpose."

Such purposes have been long suspected. New Yorker investigative reporter Jane Mayer has described in meticulous detail how military psychologists came to Guantánamo in 2002 to "reverse-engineer" the Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape program used to train American service members to outlast harsh interrogation techniques if captured. "Ideas intended to help Americans resist abuse spread to Americans who used them to perpetrate abuse," she wrote, describing interrogation techniques like blasting music (Eminem and Matchbox Twenty, among others it would later be revealed), defiling the Koran and "using sexual gambits to unnerve detainees."

That bolsters Hickman's assertion that the sole purpose of Guantánamo, teeming with minnows, was "creating an environment in which human beings could be broken down with the greatest efficiency," with the lessons learned in Cuba studiously repeated at CIA black sites around the world. There were few rules, foremost among them the one voiced by CIA lawyer Jonathan M. Fredman in the fall of 2002 : "If the detainee dies, you're doing it wrong."

As for those three deaths that June evening—the how—the case of Ali Saleh Kahlah al-Marri may be instructive. Al-Marri was a Qatari national arrested in Illinois in December 2001 and eventually declared an enemy combatant. He was eventually transported to a Navy brig in Hanahan, South Carolina. There, he was allegedly subject to an interrogation technique known as "dry-boarding," first described by Almerindo E. Ojeda, a professor at the University of California at Davis who runs the Guantánamo Testimonials Project.

According to a suit filed in federal court in 2008 on al-Marri's behalf by, among other entities, the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law, "On several occasions interrogators stuffed Mr. Almarri's mouth with cloth and covered his mouth with heavy duct tape. The tape caused Mr. Almarri serious pain. One time, when Mr. Almarri managed to loosen the tape with his mouth, interrogators re-taped his mouth even more tightly. Mr. Almarri started to choke until a panicked agent from the FBI or Defense Intelligence Agency removed the tape."

As for the notion that the three men died in CIA custody, it is plausible precisely because they weren't diabolical masterminds. According to the AP's revelations about "Penny Lane" (someone with a dark sense of humor must have really liked the Beatles: Another CIA site at Guantánamo Bay was dubbed "Strawberry Fields"), this was a site where "CIA officers turned terrorists into double agents and sent them home." The three detainees may have had little intelligence value when captured, but that could have made them precisely the sort of "converts" the CIA sought to release without arousing suspicion among jihadists. Penny Lane appears to have been shuttered for about four months after the three men died.

"Incompetence explains almost everything," Denbeaux told me, preferring that interpretation of the facts in this case to conspiracy. If incompetence explains nearly everything, then a sense of "anything goes" probably accounts for the rest. As Mark Fallon, former deputy commander of the Criminal Investigation Task Force, scanned the minutes of a meeting on how far interrogators at Guantánamo Bay could go, he saw at once how the whole sordid business would unravel: "This looks like the kinds of stuff congressional hearings are made of."

'A Nutbag'

Late last fall, I called Mike Bumgarner at his home in Tennessee. Having retired from the military in 2010 after 29 years of service, Bumgarner now works as a security manager for a nuclear fuel company in Johnson City. He had not seen Hickman's book but readily agreed to listen to passages pertaining to his command of the detention center at Guantánamo Bay. (Rear Admiral Harris, meanwhile, refused a similar request for comment.)

In conversations with me, Hickman praised Bumgarner as a "great commander" whom he'd "admired." Murder at Camp Delta is less flattering, though, with Bumgarner portrayed as jolly but bumbling, eager to play out a "Patton-esque fantasy" by, for example, insisting that the reggae song "Bad Boys" be played as troops lined up in formation each morning. Bumgarner listened patiently to these passages while, somewhere in his house, dogs barked at each other in sporadic argument. Sometimes he merely laughed; sometimes he said, "Oh my God" and explained why Hickman was wrong about everything.

Speaking in a thick Carolinian accent, Bumgarner seemed less defensive than dismayed. He said Hickman's allegation that he and Harris had covered up the nature of the detainee deaths was "absolutely not true." When I started telling him about the mefloquine theory, Bumgarner told me Hickman was "a nutbag." He was a "periphery guy" who wanted to be the hero. To do that, Bumgarner says, Hickman concocted a story that turned some of his comrades into villains.

Bumgarner claims the suicides were not only real but a sort of inevitability. The previous year, an influential Algerian detainee named Saber Lahmar had decreed that the Islamic prohibition against suicide could be lifted given the dire situation at the detention camp. More recently, Shaker Aamer—the detainee who claims to have been severely beaten on June 9—had told Bumgarner that "several of the detainees had had a 'vision,' in which three of them had to die for the rest to be freed," according to the New York Times Magazine profile of the colonel.

Bumgarner recalls a "death chant" resounding through Camp 1 on June 9. "They knew it was gonna happen that night," he told me of the suicides. "Everybody knew about this." In a subsequent conversation, I asked him why he didn't stop the suicides if he foresaw them. He concedes that, in retrospect, "we should have put two and two together and then taken action."

Bumgarner says the detainees had been given plenty of blankets, because he'd been trying to get on their good side and was acutely aware of how badly they wanted even a modicum of privacy. Asked about the testimony of the guard who claimed to have found no extra material during a June 9 cell inspection, Bumgarner wrote to me, "One thing I learned, they are very good at hiding items, plus guard complacency can cause something to be overlooked." He speculates that the detainees hid extra sheets by flattening them along their mattresses.

I asked Bumgarner if he had any doubt about the official narrative.

"None whatsoever," he said.

Some journalists have been equally skeptical of the story line promulgated by Hickman, Denbeaux and Horton. On the website for the conservative magazine First Things, editor Joe Carter listed 50 eyewitness statements from the NCIS report that backed the official version of events, and blasted Horton as "astoundingly gullible or willfully ignorant."

After Horton won a National Magazine Award for his Harper's story, Alex Koppelman excoriated his "tall tale" in the pages of AdWeek. Koppelman, now the U.S. news editor at The Guardian, was especially troubled by the notion that "Horton's main sources were perimeter guards, distant from the prisoners," an echo of Bumgarner's criticism. He also surmised that a van leaving Camp America and turning left at ACP Roosevelt did not necessarily have to travel to Camp No—a central contention of Hickman's narrative.

It is also problematic for Hickman that the most detailed description of Camp No/Penny Lane, from the AP, makes clear that most detainees were coaxed, not tortured, into cooperation, some of them even lavished with pornography: "The cottages were designed to feel more like hotel rooms than prison cells, and some CIA officials jokingly referred to them as the Marriott." (Then again, the notorious North Vietnamese prison of Hoa Lo was known during the Vietnam War as the Hanoi Hilton.)

The Pentagon has no intention of looking at the June 9 deaths again. Lieutenant Colonel Myles B. Caggins III, the Department of Defense spokesman on detainee policy, referred me to a 2010 statement that opens as follows: "Any suggestion that the suicides of three Guantánamo detainees in 2006 were actually homicides and the subsequent investigations were part of an elaborate government-wide cover-up is nonsense."

NCIS spokesman Ed Buice also refused to comment. He pointed me to another 2010 statement, which also calls the allegations "nonsense."

Not everybody at the Pentagon agrees. A highly placed source in the Department of Defense who deals with detainees' affairs, and who asked to remain anonymous because he is not permitted to speak to the media without receiving prior clearance, wrote to me in an email: "After reviewing the information concerning the three deaths at Camp Delta on June 9, 2006, it is painfully apparent the personnel involved in fact created an illusion of an investigation. When you consider the missing documents, the lack of key interviews, and the questionable evidence found on the bodies, it is blatantly obvious there was something that occurred that night that is not documented."

Hubris Unrestrained

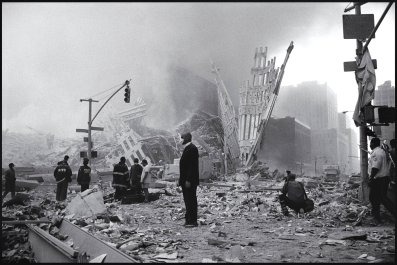

On December 9, 2014, just about a month before the release of Hickman's book, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released a report on the use of torture by the CIA during the first several years of the War on Terror. Championed by California Senator Dianne Feinstein, the report found that "the interrogations of CIA detainees were brutal and far worse than the CIA represented to policymakers," with detainees waterboarded much more frequently than had been previously acknowledged, subjected to rectal hydration and left to freeze in dungeons. One CIA interrogator said the detainees at the Salt Pit, a notorious prison in Afghanistan, "literally looked like a dog that had been kenneled."

The report—which is heavily redacted and is merely the summary of a 6,700-page investigation that remains classified—does not explicitly confirm Hickman's suspicions about what happened at Camp Delta on June 9, 2006. But it lends credence to his broader narrative, of a national security establishment certain that the smoldering hole in lower Manhattan gave it carte blanche after 9/11. Many civilians felt the same way. Many still do.

The prevailing sense, in both the CIA torture report and in Hickman's book, is of hubris unrestrained. Once in a while, sobriety intruded, caution crept in: "History will not judge this kindly," Attorney General John D. Ashcroft said as he listened to senior members of the Bush administration detail the types of torture used on suspected terrorists. But such instances were rare.

I asked Hickman why he wrote his book. The detainees are dead, and no amount of evidence will resurrect them. And even if he could prove they were murdered, the Pentagon clearly has no interest in investigating what it has already investigated. Was this all a Sisyphean pursuit?

Hickman objected. He points, first of all, to the unraveling of the myth surrounding Corporal Patrick D. Tillman. The former National Football League star became an Army Ranger after 9/11, only to be killed in the line of duty in Afghanistan in 2004. The Pentagon quickly turned the Tillman tragedy into a publicity bonanza; it took years of dogged investigation by his family and others to uncover that Tillman had been killed by friendly fire, and that great pains had been taken to hide that fact. If the military could so blatantly lie about someone as prominent as Tillman, Hickman reasons, it would have little compunction doing so about three virtually anonymous jihadists manqué sequestered in a remote Cuban prison camp.

Hickman says he wants his book to serve as a condemnation of Guantánamo Bay, of indefinite detentions and cruelly euphemistic "enhanced interrogation techniques" practiced there and elsewhere. Hickman believes the prison camp at Guantánamo should be closed and the detainees tried in federal court, as President Barack Obama once hoped they would be. Six years ago, the president said the place "likely created more terrorists around the world than it ever detained." But though many detainees have been shipped home or to countries willing to harbor them, the camp remains open. It will still be there when the next president takes his or her oath.

That does not deter Hickman. "We have to become the good guys again."