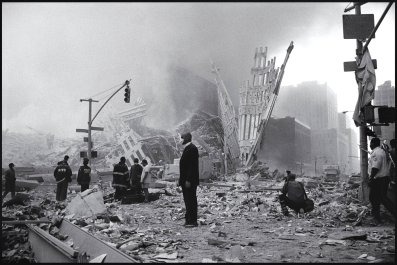

The killings at Charlie Hebdo on Wednesday have hit Syrian Tarek Alghorani hard. His girlfriend tells me he's been distant since the news first came in; the events in Paris have stirred too many memories. Tarek knows better than most the exorbitant price that laughing in the face of terror can demand.

In 2006, before Syria became synonymous with the slaughter and sectarian violence of jihad, Tarek was sentenced to seven years in the country's notorious Sednaya Prison for daring to satirise the regime of President Bashar al-Assad in his blog, Syrian Domari. After being freed in 2011, he continued his opposition to the regime that had imprisoned and tortured him, embarking with others on a graffiti campaign that would result in the deaths of his friends and, ultimately, his flight from Syria. Still, almost lost within the smoke of a busy downtown bar in Tunis, Tarek laughs. He laughs a lot. He tells me how he laughed as the judge handed down his sentence, "I looked at him and I said, seven years? You won't even be here in seven years."

For a regime that has outlawed criticism, humour presents a threat bordering upon the lethal. Many of those in Sednaya with Tarek had been responsible for acts of terror that had resulted in the deaths of hundreds. Tarek's sentence for mocking the regime was as long as any. "Funny; funny is not easy, but it's perfect for giving an idea to another. Funny draws people in. Funny gets you more followers and (for the government) that makes you more dangerous. With funny you can do anything. You can give your opinion in a smart way." Tarek pauses to ask himself a question, "Funny? Funny does everything."

Not everything is funny. There is little humour to be found in the "festival" of Falaqa that greeted Tarek's arrival at Sednaya. The animation drains from his face, "They fold your body into a car tire, so you cannot move. Then they put a thick iron bar here," he says, indicating to the back of his knee. "After that, they beat you on the legs with sticks, until you are black from the beatings. When the security services torture you during interrogation, you know that if you give them something, they will stop, even if just for a little bit. When the prison guards beat you, you have nothing. You can say nothing. It's just beating."

Similarly, there is little that could be considered funny in the murder of his friend, Nizar Rastanaoui. "They put us in with the jihadists, with al-Qaida and the beginnings of what is now Daesh, (the Arabic term for ISIS) . . . In 2008, the prisoners revolted, taking control of the prison. One group of jihadists, we never found out who, came for Nizar. They took him to another floor and beat him with water pipes. When we found him, his head was like this," he says, indicating with his hands something the size of large water melon. "We couldn't recognise him. We only knew him by the T-shirt he was wearing."

Tarek grew up in 1980s Damascus, the son of a small businessman. "They tell me I was always joking. I was always up to something, making up songs, jokes, this kind of thing." As a child he became a voracious reader, consuming everything that hadn't been censored and applying it to life within Syria. Referencing Descartes' Method of Doubt, he explains how his distrust of the regime grew, eventually drawing him inexorably to a life online. Initially he joined the internet discussion forum Akhuaia (fraternity) before, along with others, founding the satirical and political blog, Syrian Domari in 2003, eight years before social media was to drive a revolution throughout the Arab world.

Tarek was released from jail in 2011, emerging into a Syria experiencing the first throes of the secular, democratic revolution that was to tragically descend into the vicious and the sectarian. Once more, despite the beatings and the torture he had experienced, Tarek felt compelled to take up arms against the regime that had taken seven years of his life. This time he did it with an aerosol can.

"Graffiti is key, because with graffiti, you have broken the wall, broken the wall inside people's minds, because people are scared of the wall. They tell you, 'Shh . . . the walls have ears. Don't say anything'." For Tarek and his friends, graffiti equated to defiance and hope. "For more than 40 years, all we have are pictures of Bashar al-Assad and his father. Every day, that is all people see. With graffiti, we can break that. We can break that wall. When there is a demonstration and people are shot, afterwards, the television will come and say that nothing happened there and they will film it empty. With graffiti, we can say that we were there, these are our martyrs, and that we are still there."

Inspired by similar campaigns in Iran and Egypt, Tarek switched from creating graffiti, to creating the stencils by which Syrian youths could replicate the images en masse. More stencils appeared, some mocking Assad's resemblance to Hitler, others making great play of the leaked information that the President's wife, Asma al-Assad, (in Arabic, Assad means lion) referred affectionately to him as her "duck". It was a gift Tarek savoured.

Nine of Tarek's friends were killed during that campaign. Their families remain in Syria, so their identities must remain secret. However, the death of one, Nour Hatem Zahra, was publicised, his funeral drawing disaffected Syrian youths in their thousands. It is still visible on YouTube.

Tarek left Syria in 2012 after learning that, once more, he was wanted by the regime, this time – not to be arrested – but to be killed. Initially, he left for Jordan, before later relocating the relative safety of Tunisia. He now works for the Tunisian Centre for Press Freedom and has little choice but to observe the carnage that has come to characterise his home from a distance. Though reduced, his involvement in the secular, youth-led Syrian resistance remains. His latest effort, a stencil of ISIS leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was taken directly from the pages of Charlie Hebdo. "I wanted to show solidarity with Charlie Hebdo. I don't know if they'll use it in Raqqa, (the de facto capital of the Islamic State) but they might."

"Satire and magazines like Charlie Hebdo can't stop. We must still fight for freedom of expression. We can never stop. We must do it for all people, so that they can say what they want to say. If you write something I don't like, I can write something saying you're wrong. If you draw a picture attacking me, I will draw a picture back. In this way, word by word, caption by caption, we can move forward. Not with violence. Violence will not stop anything. Violence is for dictators, for terrorists. It's for everyone who wants to make us frightened. No, we will not give them that. We must continue."