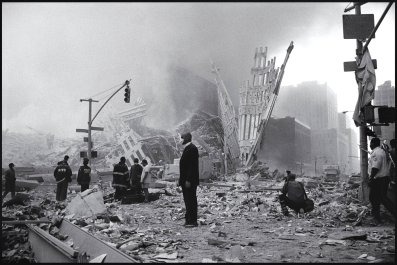

In 1964, the Stanley Kubrick movie Dr. Strangelove sported an alternate title, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. An existential atomic anxiety permeated society: We lived with the dread that just a button push could unleash new technology that would, ironically, end modern life.

It's time to feel that kind of dread about cyberattacks. North Korea's apparent hack of Sony was just a ham sandwich compared with what's coming. Now we've got a Ukrainian group shutting down German government websites. Nobody knows how to stop these attacks, which will only get more sophisticated and more treacherous. This is the atomic bomb of our networked age—a looming disaster, and a genie that can never be stuffed back down. Cyberwar does not seem as tangibly destructive and terrifying as nukes, but give it time. It will.

That's not an alarmist point of view. Among people who know cybersecurity, it's conventional thinking. "This has the whiff of August 1945," former CIA director Michael Hayden told an audience more than a year ago about hacking. "It's a new class of weapon—a weapon never before used."

Our lives are now completely reliant on fantastically complex systems controlled by computers. Those computers, by necessity, connect to networks, and those networks connect to billions of things all over the globe: supercomputers, laptops, cellphones, sensors, machines, planes, trains, automobiles, MRIs, DVRs—oh, and weapons. Complex systems are the foundation of this era of humanity. The planet can't support—would never have tried to support—7 billion people without them. Every day, we need these systems more.

If bad actors damage or take control of our systems, they could cause remarkable devastation. Pick your favorite Hollywood blockbuster scenario. Bad guys could muck up financial systems and start a global panic. They could wreck the power grid or fling open dams. Farm machinery is now highly networked: Fry all the combines at harvest time and what happens to the food supply? Others have imagined hijacking planes without boarding them; instead, just hack into connected cockpit systems from the ground. Or there's the ultimate fear that hackers could take control of some country's nuclear arsenal.

We are at the beginning of an exciting new Internet of Things, which promises to connect much of the physical world to networks. In so many ways, this technology will improve life and give us more knowledge. It could also make us vulnerable in ways we never dreamed. "I was trying to think of some strange scenario that could drive the point home, like my new Bluetooth meat thermometer," Mike Campbell, CEO of financial software company International Decision Systems, told me. "Does somebody hack that and all the rest of them too, and have the things give us all the wrong readouts until there are a million grease fires all going at the same time on Thanksgiving?"

He's not even half-joking. "You really have to have an hour-by-hour sense of paranoia now," Campbell added.

Scarier still is that there's no way to foresee who or what might launch attacks. With nukes, there's a chance of knowing who has what weapons and who might try to get them. Cyberattacks could be launched by a loner genius in a Montana shack, organized criminals in Russia, the Chinese military or an MIT-trained Taliban soldier in Pakistan. If nerds in North Korea, which is such a technological backwater that a Space Invaders video game would seem miraculous to most of the population, can mount a cyberattack, anybody can.

Actually, the worst news about the attack on Sony is that it was utterly mundane. Companies get attacked constantly. Most of the time, intruders do little damage. Break-ins are typically motivated by money: Criminals want to steal information they can sell. That's what happened to Target, Home Depot, the P.F. Chang's restaurant chain and many other companies. Sony's attackers, though, intended to do harm by destroying data and releasing executives' emails. It won't be the last time that happens. In fact, attackers will get more dastardly.

From 2009 to 2013, the number of reported invasions of U.S. military or federal government computers jumped from 26,942 to 46,605, according to the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team. That's not attempts. That's successes. How long before one of those shuts down a vital system?

Of course, giving up isn't an option. The world has to work to contain this threat, just as it did with nuclear weapons after World War II. Fred Wilson, the well-known venture capitalist, predicts that in 2015 every business and government institution, spooked by Sony, will pour money into cybersecurity. Investment in startups that have new ideas in this space will rocket. Maybe someone will hit on a breakthrough.

Somewhere down the road—a decade or longer, probably—the first commercial quantum computers might get built. They will be exponentially faster than any computer today and, supposedly, could deploy unbreakable protection schemes. But for now, in 2015, that sounds like Ronald Reagan's "Star Wars" plan to defeat incoming nuclear missiles: comforting but far-fetched.

Even with the best technology, the problem is often humans. We download a malicious file thinking it is a picture of a puppy, and it infects a whole system. Or someone operates from the inside, like Edward Snowden. As billions more people get online, we'll never secure all the humans. A Georgia Institute of Technology report on cybersecurity concluded: "Humans are no longer the last line of defense against cyberattacks, but often represent an end run around security measures."

The best hope, really, is the same kind of international effort and political tension that has prevented a nuclear attack since 1945. The world agreed that nukes were very bad, set up systems to monitor them and backed that up with an unspoken sense that any aggressor who used one would find its entire existence removed from Earth.

We're going to need the same kind of international condemnation of and action against cyberattacks. It won't happen anytime soon. The Sony attack wasn't serious enough to drive that level of change. Hopefully, it will come before a major cyberdisaster gets unleashed by hackers.

Maybe Sony can help raise awareness by remaking Dr. Strangelove for the 21st century. Subtitle: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Hack. We all need a big, broad dose of existential anxiety right now.