This spring more cranes will be fledged in Britain than for 400 years. Not only that, it's probable that, in a remarkable instance of nature healing itself, cranes will be breeding in more places in Britain than since the execution of King Charles I in 1649.

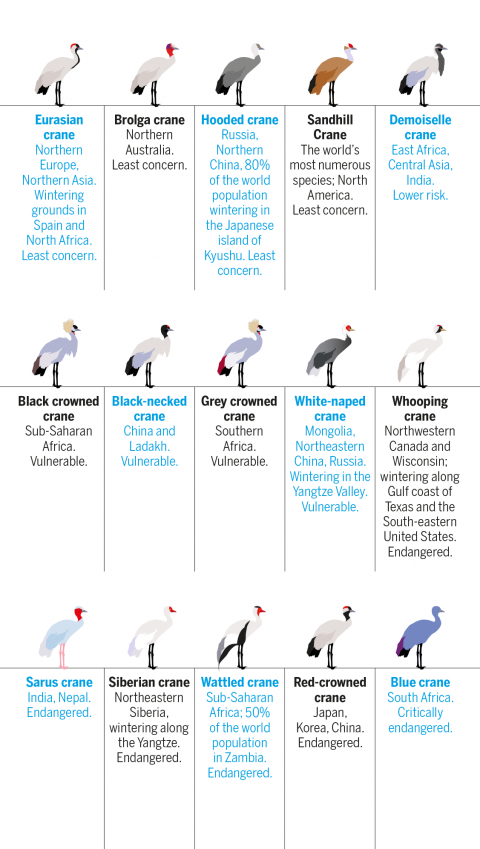

There are 15 species of crane across the world. The one found in Britain is variously called the common, European and Eurasian crane, though mostly, in the vernacular, just the crane. If you want precision, use the scientific name, Grus grus, which is onomatopoeic, recalling the birds' powerful bugling calls. They can be found in numbers in the right places in Europe, but the British managed to get rid of them altogether for hundreds of years.

Cranes demand a powerful response from humans. In some cultures, they inspire reverence: numinous birds, what the Chinese call "the birds of heaven". The Japanese say that if you make 1,000 origami cranes, a real one will grant your wish. Sadako Sasaki resolved to fold her own thousand-strong paper flock before she died of leukaemia at the age of 12, as a result of radiation from the bomb that fell on Hiroshima. The folded crane is one of the symbols of that terrible event.

Cranes are immense things: Britain's tallest breeding bird stands at 1.6m, and with a wingspan – bigger even than the white-tailed eagle – of 2.3m. They really don't look like creatures that could have a place on a small, deeply urbanised 21st-century island. But they have returned, by themselves, of their own choice; one of those spontaneous events that tell of the extraordinary resilience of the natural world. The events that have brought the crane back to Norfolk by natural means make a powerful contrast with a more recent project: the reintroduction of cranes elsewhere in the country by human means.

It is the joint effect of the natural spread of cranes over the past 30 years in the east of England, and the artificial spread in the west that could bring about a new record for breeding cranes; a kind of benign pincer-movement, as if humans and the wild world were working together without tension. Because it's important to understand that the birds can't exist by themselves, they need infrastructure – places to roost, places to nest, places to feet. These are not easily available in a crowded landscape, particularly as cranes, being big birds, need big spaces. Nature reserves, however well-managed, aren't enough. It can't be done with the odd island of wildness. You need a wild countryside.

This is a story about land management as much as birds. It's about the willingness of landowners to farm in a less intensive fashion, the willingness of government to subsidise such use of land, and the ability of land-managers to use grants full-heartedly and effectively.

At Stubbs Mill, hard by Hickling Broad in Norfolk, you can stand on the highest point for miles around. It's a bank. Its summit is a good metre above the rest of the landscape, enough for immense sweeping views. Here you will meet a handful of figures muffled in much-used outdoor gear, all with binoculars and telescopes. Birders: some hardcore, some novices, all waiting.

It is about as remote a place as you can find in lowland Britain, and marsh harriers – once down to a single breeding pair in Britain – roost there in numbers. But even these momentous birds are not the stars. For as often as not there will be an aerial bugling, a call, "Grus! Grus!" And two, three, sometimes four cranes will fly over, sometimes to land nearby, at other times to move on, sometimes to touch down just within sight.

These are birds for which people make pilgrimages. They are increasing in numbers and spreading their range. They may doing so at the speed of a glacier, but it's happening before our eyes. Cranes were once common in this country. Their names echo across the map: Carnforth, Cranmere, Cranwell, Cranborne, and, from the Nordic, Tranmere. They were regarded as the ultimate quarry for a falconer and as the centre-piece of a banquet.

The fragile colony

"Let a crane bleed in the mouth, as thou didst a swan, fold up his legs, cut off his wings at the joint next the body, draw him, wind the neck about the spit; put the bill in his breast: his sauce is to be minced with powder of ginger, vinegar and mustard."

This 15th-century recipe is quoted in Birds Britannica, by Mark Cocker and Richard Mabey. Cranes are birds of wet places. They nest on the ground, and they like to be as nearly surrounded by water as possible. So when England's watery landscape began to be drained for agriculture, the birds were caught in a double bind: the combination of habitat destruction and persecution made sure that they vanished from British life. Save for occasional passing strangers lost on migration, they weren't seen in the UK for around 400 years.

Fast forward to the 20th century. John Buxton, a wildlife film-maker, lived and managed Horsey Estate just inland from the East Norfolk coast. His father had bought the place in 1930 and he managed it for wildlife, encouraging reedbeds and keeping plenty of water on the land. In September 1979, a tenant farmer with cattle on part of the Horsey marshes told Buxton: "I've just seen the biggest bloody herons I have ever seen in my life." They turned out to be three cranes, birds who had got a little lost on their migration from Scandinavia to their wintering grounds in southern France and Spain. Horsey Mere looked inviting from the air, especially to a tired bird, and so they dropped in. Against all expectations, they stayed for the winter. When spring came, they set off, presumably to try and find Sweden, but after a while they returned to Horsey and stayed for another winter.

In the spring of 1981, a pair of cranes made a nest, laid two eggs and hatched one chick, which was lost, presumably to a predator. The following year, the pair nested in the same place and this time hatched and fledged a chick, the first British native wild crane for all those centuries. It would be a remarkable enough story if it ended there, but it didn't. More wild cranes dropped in and, very slowly, the numbers increased. The group of birds could now, in its modest way, be called a colony. They were re-establishing themselves as part of British life.

In the early days of this rejuvenation, the cranes were surrounded by a desperate, perhaps rather paranoid, security. It's a fact that a British-laid crane's egg would be of incalculable value to the criminal cult of egg-collecters. There were also fears that too-eager bird watchers would crowd the cranes and affect their breeding success.

Horsey Estate had some advantages over official nature reserves with public access; it offered the cranes a very real seclusion. Subsequent events seemed to demonstrate that cranes can withstand a bit more proximity to humanity than was first thought, but perhaps the initial insistence on leaving them well alone was a necessary step.

Nevertheless, it was becoming impossible to deny that cranes existed in Britain – after all, they are not easy birds to miss. Besides, the business had been an open secret in birding (and presumably egging) circles for years. So, as the birds grew in number and began to spread out away from Horsey, so their presence could be celebrated as an inadvertent triumph.

The RAF station at Lakenheath, Suffolk, hosts the 48th Wing of the USAF. It's in the Fenland marshes, and surrounded by carrot fields. Twenty years ago, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) bought up some of these fields and restored them to original fen: an audacious and wholly successful project of rewilding.

Again, this is a remarkable enough thing in itself – but in 2007, far beyond the expansive hopes for the reserve, two pairs of cranes nested there. The reserve is open to the public, the accessible areas were merely adjusted a little so as not to upset the cranes.

At another RSPB reserve, one not open to the public because of the fragility of the habitat, a pair of cranes nested for the first time last year. They could be heard bugling away in the site office, and could be observed from the office door. Cranes now nest on Humberside and in Northeast Scotland as well.

Ian Robinson, Broads area manager for the RSPB, does a great deal of liaison work in Norfolk with the farming community. He advises them how to apply for and get grants from The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and how to implement the conditions of the grant most effectively.

At Berney Marshes there is an RSPB reserve surrounded by privately-owned land and you can't tell where one begins and the others end. It's a classic example of the good management of marshland for humans and for wildlife and such thinking is at the heart of the return and the spread of the cranes.

The same thing is true on the Somerset Levels, where there are projects in place aiming to combine work for wildlife and for flood relief, a landscape managed with bigger aims than quick profit. And it's here that the cranes were reintroduced. They have settled in and some of them are now trying hard to produce young.

A pair has split off from the main group and went to the Wildfowl and Wetland Trust reserve at Slimbridge. This is a much visited place, but the cranes have shown no inhibitions about breeding there. At the beginning of March it was reported that they were getting ready to try again. This is the third year they have attempted to breed here in full public view, and now that they are more experienced and street-wise, they have a greater chance of pulling it off. Cranes are long-lived birds that can take setbacks in stride. This success story is balanced on a knife-edge, as all such projects are. There really aren't many cranes in Britain around – fewer than 200 – and no more than a good handful of pairs attempting to breed. They are still, in British terms, operating on the edge of the possible.

But what cranes demonstrate most clearly, in their dramatic way, is that a benign way of running the countryside is one that operates much better for wildlife, and has immense benefits for humans as well, in terms of the benefits that come from a cleaner and healthier environment. Nature had the most extraordinary ability to selfheal – but it only works if humans are prepared to meet it halfway.

The Great Crane Project

The Great Crane Project began in 2010 on the Somerset Levels, a perfect crane habitat. Cranes undoubtedly bred there in past centuries, but they were unlikely to return spontaneously. The project was set up by Wildfowl and Wetland Trust, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and Pensthorpe Conservation Trust.

Over the next five years 93 birds were hand-reared from eggs collected from the robust German population and were eventually released into the wild. This was a weird, near farcical business, in which the operators took immense pains to make sure that the cranes didn't become too accustomed to humans, and lose their crane identity and their vocabulary of crane behaviour. In order to live in the wild, these birds had to be properly wild themselves.

The endeavour led to comic scenes of handlers wearing smocks and hoods to disguise their human shapes, showing crane chicks how to forage with the use of dummy crane heads, which they held in their heavily disguised hands. The cranes began their lives in an enclosure, and as they acquired competence, the roof was removed. Gradually the cranes began to spread out.

As the result of these intensive and complex procedures, the cranes have been successfully introduced to the wild and shown themselves perfectly capable of fending for themselves. There are 75 of the original 93 still alive, more than hoped, as a third were expected to be lost. But this is only the first step. The cranes must proceed without human assistance: pairing up, mating, laying eggs, raising and feeding young and then successfully fledging them.

Cranes rarely breed before they are four. The target is 20 breeding pairs by 2025. The birds can survive the English winter and cope with other challenges: so now their task is to make more cranes that are capable of doing the same thing.

It's highly possible that this year will be the turning-point: that the first crane hatched and raised in the wild at Somerset Levels will take wing and fly.