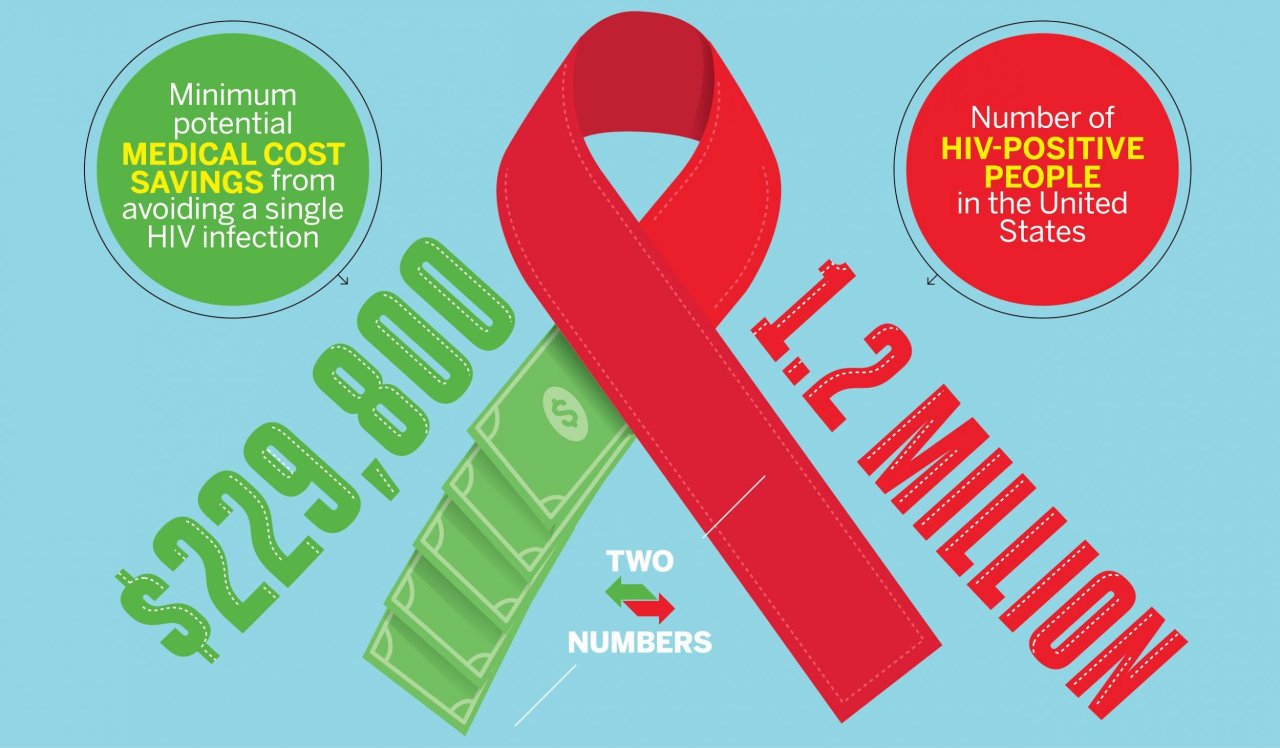

With an estimated 1.2 million people in the United States living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and an estimated 50,000 new diagnoses every year, policymakers must decide how to split funds between treatment and prevention programs. To help with that decision making, researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College and a handful of other schools and agencies determined the medical cost saved by preventing a single HIV infection: between $229,800 and $338,400.

The researchers, who recently published their findings in the journal Medical Care, used computer-simulation modeling to map out the treatment and other medical costs for a hypothetical 1 million people who become HIV-positive at age 35, the mean age of infection in the U.S. Using hospital data and the consumer price index to determine the costs of medications, antiretroviral therapy (ART), hospital and clinic visits, and lab tests, the researchers found that someone who is HIV-positive will typically spend $326,500 on medical care in a lifetime. More than half of that is for ART, a drug cocktail intended to keep the virus from reproducing. That number also takes into account costs associated with other illnesses, because people with HIV are more prone to those.

For someone who isn't infected but considered to be at higher risk, such as gay men and African-Americans, researchers simulated another 1 million people and found the lifetime medical cost to be $96,700. They subtracted that number from the figure for infected people ($326,500) and determined that preventing someone from becoming infected saves $229,800, based on what the researchers call "current patterns of HIV care in the U.S." In such patterns, not everyone who is infected seeks treatment right away or sticks with it. But if people did do those things, the savings for preventing a single infection could be $338,400.

"There's a greater focus these days on prevention because the number of people with infections has not gone down in the U.S.," says Bruce Schackman of Weill Cornell Medical College, the study's first author, referring to the fact that HIV rates have been mostly stable for the overall population since 2008. He adds that there is increasing interest now in pre-exposure prophylaxis, or daily preventative medication, which can be costly. "That's why looking at the costs saved is an important piece of the puzzle," he says.

"We live in the era of limited resources," says Elena Losina of Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Boston University School of Public Health, a co-senior author on the study. With more than a million people living with HIV and more becoming infected all the time, we need to make smart choices about how to distribute resources, she says, "and the question between prevention and treatment is always a heated debate, because obviously the value of treatment is easier to show."

In a study that is the first of its kind, Losina says, "this report helps to assign a value to prevention strategies."