Alen Muhic was 10 years old when a fight with a playground bully broke his family apart. Until then, the gregarious little boy, who was obsessed with airplanes, had believed he was from a typical Bosnian family, that his father was called Muharem, a janitor at the local hospital in the town of Goražde, that Muharem's wife, Advija, was his mother and that their two daughters were his sisters.

"It all started with a typical childish quarrel over an insubstantial thing," says Muhic. "We were attacking each other saying, 'You did this and you did that', and so forth. Then he hit me and I hit him back and, in an explosive outburst of anger, he started yelling and screaming at me: 'You filthy scum, you are adopted, your mother abandoned you, you bastard, you Chetnik bastard, you Chetnik baby! You were found in a filthy waste bin and then you were adopted!' I felt utterly bereft. I was so ashamed to hear those words. I hit him once more and then I ran the one and a half miles home, crying all the way."

Today, Muhic little resembles that broken little boy. He is tall, handsome, witty and spirited as he speaks to Newsweek about the quest to find and contact his real parents, which began shortly after that day in 2003. In the years since, he has told his life story through two documentaries about the children of rape in the Balkans, with the single aim of tracking down his biological parents. Sitting in a cafe in Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in January, Muhic and the director of both documentaries, Šemsudin Gegić, explain how through a series of extraordinary coincidences, the little boy was able to succeed in tracking down his mother and father.

When Alen reached home, red-faced and in tears, his parents realised that the moment they had been dreading since the day Muharem first brought a bundle home from the Goražde hospital's maternity ward to entertain his little daughters, had finally come. The Muhics and their neighbours and friends had always known the truth about Alen – that he had been born in February 1993, to a Bosnian Muslim girl repeatedly raped by a Serbian soldier, who had gone to the abortionist too late, and been forced to give birth to a baby she confessed she wanted to strangle.

"My mother left me right after giving birth to me," says Muhic. "She didn't even breastfeed me, not even once . . . never. She just left."

"Little Chetnik"

The locals were not the only ones who knew the truth about the Muhics' little boy. When Alen was three years old, in 1996, Newsweek reporter Stacy Sullivan wrote his story, recognising him as a product of one of an estimated 20-50,000 rapes that occurred during the war in Bosnia from 1992-95. Sullivan had tracked down Alen's mother too, who spoke chillingly of her feelings towards the baby she had abandoned and its father, the man who, she said, had wounded her "in a way that I will never heal".

"When I heard him cry, I asked the doctor to bring him to me. I wanted to strangle him," Muhic's mother told Newsweek in 1996. But she didn't. Instead, she abandoned him in the hospital, where a repairman fell in love with the baby and began taking him home to his wife and children during the day, bringing him back to sleep at the hospital at night. The girls were besotted; they had always wanted a brother. Eventually, the couple formally adopted the little boy, and brought him home to the Muslim enclave, where food was scarce, and there was no heating or running water.

"I love him so much, more even than my own daughters," Advija Muhic had told Newsweek then. "I don't know how I'm going to tell him, but I must."

Even in 1996 there were signs that the secret might come out. Newsweek's reporter noted that neighbours, wise to the circumstances of Alen's birth, had already begun to describe him as the "little Chetnik", a derogatory term for a Serb. He had acquired another nickname too, "Pero", a common Serb name, and, even at the age of three, Alen seemed aware of the name's pejorative connotations. "I hate it when people call me Pero," he'd told Newsweek, "I just hate it".

Once the truth was out, life was difficult, Muhic admits. "My parents treasured me as their most priceless possession," he says, but others were hostile and "people kept repeating that I am Chetnik bastard who was found in a smutty trash can. But people will always spread rumours about you: that's the way the cookie crumbles".

In Bosnia of the early nineties there was a fiercely enforced omerta surrounding the topic of war rapes. While most rape-induced pregnancies were aborted, some women, like Muhic's mother, were too far along by the time they went to the doctor. After birth, these children were mainly discretely abandoned in hospitals, known collectively as "children of hate" and raised together in orphanages, whose authorities carefully hid the truth from prospective adoptive parents. Muhic was lucky. Many children like him never found homes.

The Boy on the Movie Set

In late 2004, when Muhic was 11, Šemsudin Gegić made his film, A Boy From A War Movie about the story of Alen's life. It happened almost by accident.

Taking a walk through a nearby village, Medjedja, Alen happened to walk into a shot of the film in the making. "We were filming a scene and an unknown boy suddenly, unexpectedly and coming totally out of nowhere, walked into the shot," says Gegić. "He was going down a slope and he was walking straight towards the camera. He approached us and asked, 'What are you doing? What are you filming?' The director of photography and the rest of the film crew sternly told him to be quiet but I let him talk. When I told Alen that I was making a documentary, he responded: 'I've got the documentary that is way better than yours!' That's how we started."

After the release of the film, which won multiple awards, Alen became a minor celebrity in Bosnia. CNN, Sky News and Channel 4 queued up to interview him. "The documentary enabled me to lead a good life in terms of standard of living and made me a 'star' on a local level. On the other hand, I had clearly made enemies in my rise to 'stardom'," says Muhic. "The documentary really shut them up because I made my personal life public. As soon as the filming was done I felt enormously relieved, as if some heavy burden of shame was lifted from my shoulders." The documentary makers had found his mother, using the hospital records and information from Muharem, and had persuaded her to give them a tearful video interview. She refused to meet Alen, however.

Once he had finished high school education, Muhic decided in earnest to contact his biological parents – and to have a camera present when he did so, in two separate meetings. Those meetings have become the subject of Gegić's second film, as yet unreleased, and the two men refuse to answer specific questions about what, if anything, has occurred between Muhic and his parents.

Trial and Acquittal

In its story in 1996, Newsweek had spoken to both Muhic's biological mother and the man she accused of having raped her. At the time, she was living in Sarajevo, but she claimed that her rapist was a local boy from Miljevina, the coal-mining town in eastern Bosnia where she grew up. He was a married Serb, she said, one of her neighbours, and he first attacked her after the town was captured by Bosnian Serb forces in April 1992.

"When he was done, he slashed her with a knife, held a gun to her head and threatened to kill her if she told anyone," the Newsweek article said. "He continued to rape, beat and threaten her several times a week." By the time she had escaped to Goražde, it was too late for her to have an abortion.

When she spoke to Newsweek, Alen's mother said she was driven by a desire for vengeance; she wanted to expose Muhic's father publicly: "But I want to do it at The Hague," she said, "There is not punishment strong enough for what he has done to me". Told about her abandoned son's good fortune, she seemed pleased, even if for an odd reason: "I'm so happy he is alive," she told Newsweek. "That child is my only proof." Acting on her information, in 1996 the reporter visited the man in question, still living in Miljevina, and confronted him with the accusations. He laughed. "Why would I rape her?" he asked, "She wouldn't be worth it". Alen's mother now lives in New York, and has two more sons of her own, but visits Bosnia regularly. She has said that she doesn't want to meet her first son.

Muhic now hopes to confront his father. He says that, while he has been approached by other mothers of children born out of rape, including one who was just 12 years old when she was raped in Foča, eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, during the war, others have claimed his primary motivation in meeting his biological father is pecuniary. "They say I wanted to grab his properties, or even to live with him in the same household," he says. "The difference is that I have never condemned my mother, but, as a rapist, my father deserves my unequivocal condemnation. He must take full responsibility for what he has done, instead of hiding like a coward. For me, he is a war criminal. Everyone who did what he had done is a war criminal regardless of whether they were Muslim, Croat or Serb," he says.

Gegić says that when the two men, accompanied by the whole film crew, attempted to doorstep Muhic's supposed father, they found the house empty. "He was tipped off by someone, telling him that we were approaching his house so he ran away right before we came to the address. More than that, he even sold his house shortly after that episode, upon finding out that Alen wants to meet up with him."

However, Gegić claims he is in possession of a court verdict, which is undeniable proof that Alen's father is a war criminal. According to Gegić, it details that Alen's father was arrested, almost a year after his first documentary aired in 2004, at the behest of a public prosecutor, on charges of repeated rape that took place in Foča and that he was put on trial. He was found guilty on all charges, says Gegić, and sentenced to five and a half years in prison. During his imprisonment, however, the case took an unexpected twist. Two protected witnesses were introduced into court proceedings.

"He was subsequently acquitted of the charges," says Gegić. "The acquittal was mainly a consequence of the DNA test result that confirmed he was Alen's birth father."

Just before sentencing, Gegić says. Muhic's supposed birth father addressed the court asking whether he could establish contact with Alen, get to know him better and perhaps even recognise him as his lawful son. The request apparently significantly affected the court's final decision on his acquittal. They made clear to him that if Alen ever needed to turn to his birth father, then he would be obligated to help his lawful son.

"His father's response – and I emphasise that Alen's father was acquitted thanks to Alen himself – was that he does not consider Alen his lawful son, claiming that Alen's real father is another Serb. He said that while the camera was filming. He also added that he doesn't believe the DNA paternity test results. As a consequence, he puts his family home up for sale and just runs away from everything to avoid facing Alen," Gegić says.

The Invisible Children

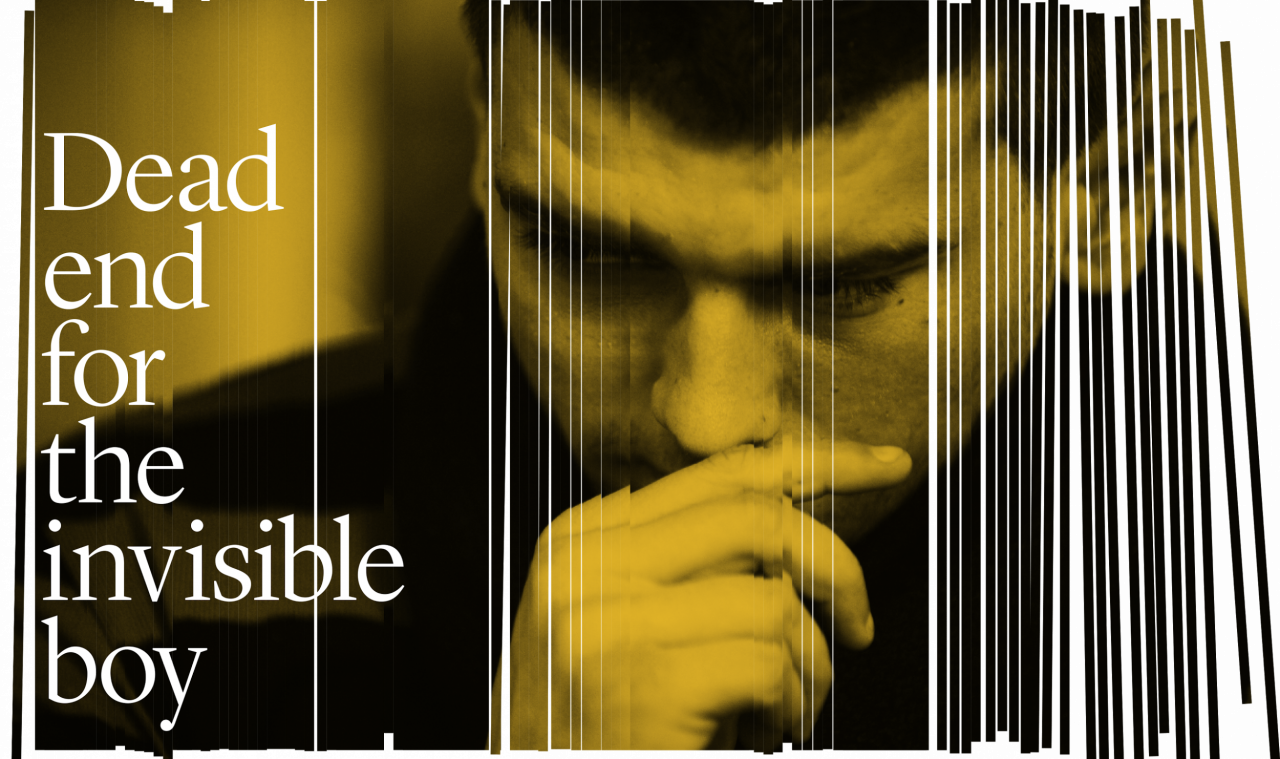

Gegić is cagey about the content of the second documentary, the title of which roughly translates as Dead End for an Invisible Boy but is happy to talk about the reasons he has for making it.

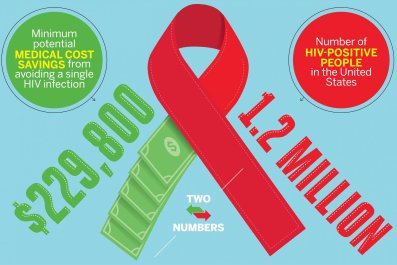

"By capturing Alen's life I tried to open up issues concerning thousands and thousands of children all over the world who suffer the same fate," he says. "At scientific conferences those children are already labeled as 'invisible children'. While we are walking through the most beautiful cities on earth we encounter – without even knowing it – thousands of kids whose mothers became pregnant with them after being raped, sometimes being raped repeatedly. So Alen is a metaphor for all those kids." The latest film is supported by the Sarajevo University Institute for Research of Crimes Against Humanity and International Law and, prior to the filming, a wide-ranging survey was conducted in an attempt to establish some facts about rape during the Bosnian war. It was proven without doubt, Gegić says, that more than 25,000 women, mainly Bosnian Muslims, were raped between the years of 1992-95.

"If all those children, who were born as the result of their mothers being raped during the wars worldwide, were to be put in a line, then the line would form a queue substantially longer than the Great Wall of China. Taking into account the number of war children, the region of former Yugoslavia has the worst reputation," Gegić says.

As long as these crimes remain unacknowledged, Gegić considers the conflict that raged for almost a decade in former Yugoslavia to be continuing. "If the stop had been put, I would have never made the documentary portraying Alen," he says. "In this part of Europe there is a fine, thin line between love and hate. And one can hardly discern where love ends and hate begins. Nationalisms and religious bigotry were quite alive even in the pre-war period, but during the wars, they increasingly became lethal and poisonous in the literal sense. In addition to that, there was a military strategy that consisted of retributive punishing of the innocent by men who were losers on the battle ground. It was these men that decided to rape women as a revenge for being incapable to conquer Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole."

He is willing to be drawn out a little on the nature of Alen's first meeting with his father. "During their very first short encounter, Alen's father refused to meet up again and that was one of the most emotional scenes I have ever seen," he says. "I am sure the audience worldwide will respond very emotionally. The scene ends with Alen's words: 'Tell him that he can hide even in the deepest underground but I promise I shall find him anyway'."

Alen nods: "The only thing I want is to look my parents in the eyes and ask them a couple of questions. I just want to meet them, not to live with them. I don't want to say goodbye to my current life. Why should I do that? I don't ask anything of my biological parents, I just expect them to somehow answer my questions as to 'how' and 'why'. Nothing more than that. That's it."