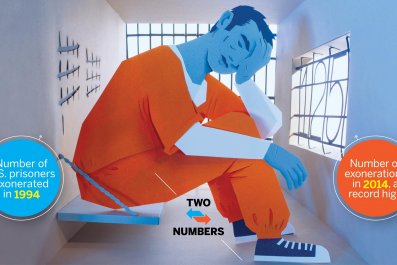

I have no idea for sure whether Amanda Knox is guilty of the murder of Meredith Kercher. In fact, perhaps no one but Knox, her Italian boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito and Rudy Guede will ever know with 100% certainty who was there on 1 November 2007, when Kercher's throat was slashed in a back bedroom in the house the two girls shared in Perugia, Italy.

The elusiveness of the truth for the past seven years is why the murder of one young woman turned into the biggest media spectacle of modern times. It is now in the news again with the ruling in Italy's highest court, and a movie, directed by Michael Winterbottom and based on my reporting for Newsweek, has just reached the cinemas.

But for those of us in Italy who covered the case from the centre ring of the circus, watching it evolve from "just another story" to something so extraordinarily out of proportion is still mind-boggling. I have wondered so many times how things got so out of hand.

In those first days after Kercher's body was found, the media scrum was mostly Italian. Then the British beer-guzzling tabloid brigade descended on Perugia. There were photographers hiding in bushes and money flying around for exclusive interviews with students, cops and lawyers. Then came the big-name anchor people from the American television networks, the bloggers from the underbelly of the internet and the trial tourists who were there just to be part of the scene.

A cottage industry sprung up dealing in interviews and "murder marketing" for "Free Amanda" T-shirts and coffee cups. Suddenly lawyers were trying to charge "photocopy fees" for access to their clients, and even Knox's family was paid "licensing fees" for photos. That's why so many interviews by those who wouldn't pay were done in coffee bars and on street corners, since stalking a source was the only way you could talk to them without reference to compensation. One colleague even interviewed a lawyer in a lingerie shop while he bought his wife a Valentine's Day present because it was the only way to talk to him for free.

The American TV networks, especially, were generous to the Knox family, paying for airline tickets and meals when trials were in session. On the night of one of the verdicts, a high-powered American producer even babysat Knox's little sisters in exchange for God only knows what. And because Kercher's family rarely came to trial – after all, no media outlets were paying their airfare – the victim slipped off the front page.

We, the Italian-speaking media covering the case from Perugia, were unable to be seen to be covering the case objectively, and instead we were grouped into camps that became like extreme political parties: "innocentisti", who thought Knox was being railroaded, or "colpevolisti" who thought she wasn't. I received hate mail from strangers accusing me of not sticking up for the American girl, some wishing me "a fate like Meredith's". I even got a nasty note from Knox's stepfather telling me I seemed like someone "who was abused as a child".

Things were drastically different in the beginning, before the first verdict. I remember drinking at a back table of the Joyce Pub in Perugia with Knox's mother, who, distraught and desperate, sobbed as she held my hand and pleaded with me to believe her daughter. She knew all the journalists by name but said she never read anyone's stories unless they were pro-Amanda. That was back when even she could be seen talking to the colpevolisti.

All of that changed when more big name media types got involved, and when the idea of an American "innocent abroad" made good morning TV. The story lost its way completely when Knox's PR firm started trading family interviews for positive coverage. If you quoted both sides or mentioned damning court evidence, you could bet you'd hear that they didn't like the reporting. Soon people who needed the Knox family on TV only quoted their side of the story, and the truth disappeared for good.

During filming for the movie, Face of an Angel, I went with Michael Winterbottom to Perugia and took him out with the press pack once we all filed our stories and were ready to unwind. That post-trial camaraderie was the best part about the case for a lot of us. I can't count the number of times we had to meet secretly so the Knox clan wouldn't see the innocentisti hanging out with the colpevolisti pack. Winterbottom was rightly horrified to see what it was like inside that little Perugia club: all of us meeting late at night after deadline to eat steak tartare and drink gallons of red wine while we discussed knife wounds and blood splatter patterns.

And media interest in the case is not fading away. It is a mystery with beautiful people, sex, lies and murder – the perfect plot for story. But perhaps the picture we should keep in our minds is not of "foxy Knoxy" at all, but of the Perugians who filled the streets when she was acquitted, holding pictures of Meredith and crying, "Shame! Shame!"