The Oakland Unified School District's Office of African American Male Achievement is housed in a one-story portable classroom in the downtown neighborhood of Grand Lake. There are few windows in the barely glorified bunker, which may be for the best: They would just let in the incessant hum of the adjacent MacArthur Freeway. The only bathroom is across a parking lot, which is lined with a phalanx of similar portables painted a deceptively alluring sky-blue. It is somehow fitting that the highway thrums but a few feet away—maybe it reminds those who work here that the goal is to whisk the city's young out of Oakland, to Silicon Valley, to San Francisco, to any place that is better than this place that they have always known.

About three miles to the north, at 809 57th Street, is the former home of 1960s radical Bobby Seale, a modest bungalow that sold three years ago for $425,000. In 1966, the year he helped start the Black Panther Party, Seale and fellow founder Huey Newton drafted a 10-point program for the black power movement in the dining room of that house. The fifth of those demands concerned schooling: "We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society."

Most people remember the Panthers for their militancy, not their pedagogy. However, in 1969 they started the Free Breakfast for School Children Program at the St. Augustine Church in Oakland, the first initiative of its kind in the nation. "It is impossible to obtain and sustain any education," the Black Panthers wrote in the fall of that year, "when one has to attend school hungry."

Today, there are still plenty of empty stomachs in Oakland: About 71 percent of the children in the school system are in the reduced-cost or free lunch program. To qualify for free lunch, a family of four has to have an annual income of $31,000. Unemployment in "the flats"—the poor black enclaves of East Oakland—may be as high as 28 percent, five times the national rate. And it is black boys who suffer most from this nexus of urban ills. In a recent series, the San Francisco Chronicle found that between 2002 and 2012, "the number of African American men killed on the streets of Oakland has nearly matched the number who graduated from its high schools ready to attend a state university."

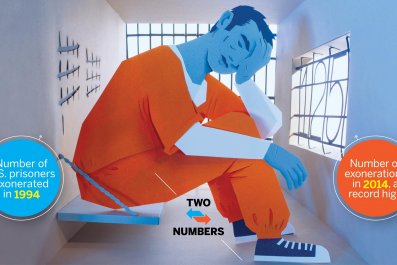

The plight of Oakland's young black boys is replicated nationwide. We may as well state plainly what we all know: Black men are this nation's outcasts, marked like Oedipus for doom from birth. They are more likely to ditch school, more likely to be arrested, more likely to end up in prison. When they are not forgotten, they are feared. When they are not scorned, they are pitied.

The handful of people in that portable classroom near the freeway is trying to change all that. Maybe they are delusional, but maybe they are more realistic than they first seem. Oakland's Office of African American Male Achievement is the first public school department in the country devoted to a problem Seale and Newton grappled with: Black boys know they are society's castaways and, often, act accordingly. In his prison memoir Soledad Brother, Black Panther George Jackson wrote that he was "born a slave in a captive society" and all his life was "prepared for prison." So are many who have followed, nudged by unrelenting fate from one bad choice to another, from misdemeanor to felony, from sentence suspended to conviction upheld.

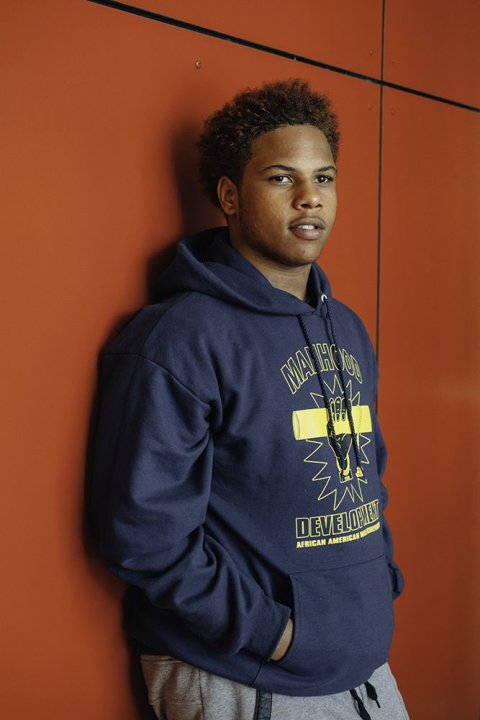

The experiment now being conducted in Oakland is to have black male teachers instruct black male students in an elective class called the Manhood Development Program (MDP), which currently enrolls about 450 of Oakland's 6,500 black male students. The number is meager, but the ambition is vast: instill black boys with self-respect, even pride, and send them out into the world with the conviction that they can be scientists and bankers, not just ballers and rappers.

"From nigga to king" is how Christopher P. Chatmon, who heads the Office of African American Male Achievement, describes his mission. Though he is irrepressibly optimistic (and occasionally messianic), Chatmon picked a tough place to work his magic: Oakland has never recovered from the tumult of the late '60s, the struggles of that era haunting the city throughout the decades since.

Today, tech money is starting to creep down Shattuck Avenue from Berkeley, and, yes, there are hipster saplings turning the Temescal neighborhood into a Portlandia parody. But there isn't a united Oakland that shares both the newfound wealth and the long-standing burdens of poverty. There is, instead, a white Oakland, a black Oakland and a brown Oakland, and on those rare occasions when those Oaklands speak to each other, the conversation is often impolite.

Nevertheless, the MDP has proved that urban despair can be pushed back, however slightly and slowly. When we met last month, Chatmon told me it will take 10 years for the program to prove its worth with the kind of statistics education reformers crave: graduation rates, test scores, college placements. A highly laudatory (though stat-poor) evaluation by the University of California at Davis argues that the MDP is succeeding in key areas like reducing suspensions and improving literacy and, even more important, getting young black men to realize they are not doomed. How do you tell a black kid to concentrate on his SAT prep while, nightly, the tragic visages of Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice flash across the screen?

The program dovetails with the federal My Brother's Keeper (MBK) initiative, announced last year by President Barack Obama. MBK shares many of the traits of the MDP: ambitious but vague, earnest yet realistic. Both programs are desperate to convince black men and boys that there is hope. How do you quantify that? Maybe you don't. Maybe you just do your best and don't look back.

'Teachers Are Afraid of Me'

"We might hope, and even expect, that school would be a place where black males are nurtured and supported, where they receive encouragement to excel," writes New York University professor of education Pedro A. Noguera in his 2008 book The Trouble With Black Boys. Noguera notes that the opposite is true, with black male students "more likely than any other group in American society to be punished (typically through some form of exclusion), labeled, and categorized for special education (often without an apparent disability), and to experience academic failure."

Noguera concludes that "the failure of black males is so pervasive that it appears to be the norm and so does not raise alarms."

The schools of Oakland hint at the disconnect between American teachers and their students. Of the 1,911 teachers in Oakland, the majority (53 percent) are white, though only 12 percent of the student body is of the same race. Most of the 32,000 students (69 percent) are either black or Latino. Nationally, about three-quarters of all teachers are female, and about 83 percent are white. "We know it's important for students to see something of themselves in their teachers," says Dana Goldstein, author of The Teacher Wars. "It can be transformative to recruit more black teachers and male teachers to the profession, to serve as role models." Chatmon saw this, too, figuring that black boys had no will to succeed because they had little notion that someone who looked as they did could succeed.

Chatmon, who has seen three sons through Oakland's public schools (one now goes to high school in Berkeley), is from San Francisco. He first went to community college in San Mateo, then San Francisco State University. He taught physical education at the Marin County Day School, in the affluent white suburbs across the Golden Gate Bridge. "It was like summer camp," he says, with an abundance of resources and capable teachers who cared. When they taught a lesson about the rain forest, he recalls, they turned the classroom into a rain forest. Later, he went to Brown for a master's degree and taught at the Wheeler School in Providence, Rhode Island, another place of privilege. The experience could have made Chatmon angry; instead, it made him hungry. It showed him "what schools can do." He went back west and started teaching at Thurgood Marshall High School in San Francisco.

In the late aughts, Chatmon ran three YMCAs in Oakland and, after that, a YMCA-based high school in San Francisco. He knew Tony Smith, then the superintendent of Oakland's schools. In the summer of 2010, the two had breakfast. Smith was dismayed by all the indicators for black boys and wanted Chatmon to do something about it. Smith had captained the football team at the University of California at Berkeley and later played in the National Football League. He told Chatmon, "I'm gonna bust a hole in the gap and hand you the ball."

Chatmon shared Smith's sense of urgency: "For a father of three boys, I can't wait 10 years for systems to change. I need something now." Handed the allegorical ball by Smith, he bolted madly for the end zone. He hasn't, as far as I can tell, glanced over his shoulder since.

Chatmon describes the MDP—which started in the spring of 2011 in three schools, serving only 50 students—as an "immediate response" to the concerns he heard from black children during a "listening campaign." Even at the elementary level, black boys were acutely, dismayingly aware of how society at large saw them. "The teachers are afraid of me," he recalls them saying. "They don't want to talk to me. They don't want to engage with me." These raw feelings were coming from boys barely old enough to ride a bike. Once that injury hardens into anger, no parent or teacher can break through it. To fend off potential foes and do-gooders alike, there is the permanent armor of 'hood survival: the flat brim cap pulled low over the eyes, the menacing gait, the lupine scowl.

Chatmon knows he can't fix all this, but he may provide a model for black boys to see themselves as more than just the next victims of police brutality. And for their fellow Americans to see them as more than felons, whether actual, possible or imagined. "The nation is ready for something positive," he says.

Handcuffs and Hugs

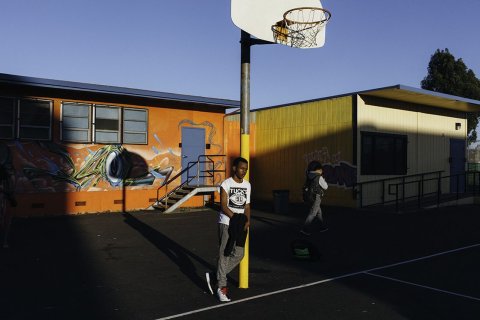

The Alliance Academy is in the chronically distressed Oakland flatlands. It has become an axiom of public education that the more aspirational the name of a school, the worse the surrounding neighborhood. Accordingly, Reach Academy, Aspire Monarch Academy and Barack Obama Academy are all nearby. The sheen of optimism comes off easily, though. Two blocks away from Alliance Academy is Verdese Carter Park, built on soil once permeated with lead. A few miles north is the Fruitvale stop of the Bay Area Rapid Transit system, where in 2009 black teenager Oscar Grant was shot to death by a white police officer.

In 2013, a video shot at Alliance appeared on West Coast newscasts. A white male teacher (a substitute) pushes a black female student out of a classroom. She is a seventh- or eighth-grader; the teacher appears to be middle-aged. The girl barges back into the classroom, swinging. The teacher charges at her with a desk, like a matador trying to spear a bull. She deflects the assault, and they continue arguing, two crazed voices matching each other's senseless rage.

For all the young men and women in Oakland who watched the fight, the encounter surely provided what educators call a "teachable moment." Unfortunately, that lesson is unlikely to make anyone a productive member of society. This is the milieu in which Chatmon works, and works against. If he can, for starters, simply convince a kid yearning for lifetime membership in the Crips that Mr. Rosenberg's lesson on Hamlet is not the most pointless way to spend 45 minutes on a radiant Friday afternoon, then Chatmon should maybe get a Nobel Prize.

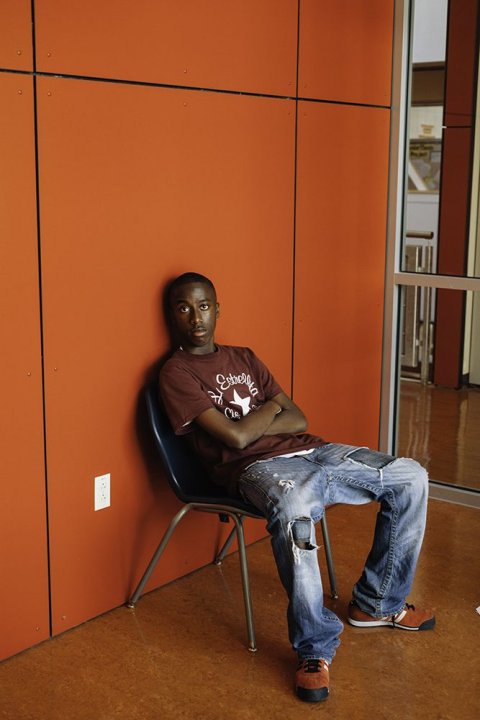

Armon Hurst, 14, is a student at the Alliance Academy. His mother, Queliya Hurst, proudly places his current grade point average somewhere north of 3.8. Nevertheless, she says, Armon struggled with self-control, which is why she enrolled him in the MDP. She says people don't understand how sensitive black boys are and how few role models they have. At the minimum, the MDP is "somebody to give you a hug, sit down and talk to you."

A skeptic might note that the distance between a hug and Harvard is dismayingly vast. Chatmon knows it. But he also knows that a hug might keep his students out of handcuffs.

The Perils of Being Book-Smart

On an overcast winter day, Chatmon and I drove to Montera Middle School, in the hilly Piedmont Pines section of Oakland, in the better part of town. The school reflects the diversity of the Bay Area, with many black (39.7 percent) and Hispanic (20.3 percent) students but also plenty of Asians (9.8 percent) and whites (21.4 percent). Yet in the MDP class taught by "Mr. Kevin," all the eighth-graders were black boys, taught only by black male teachers.

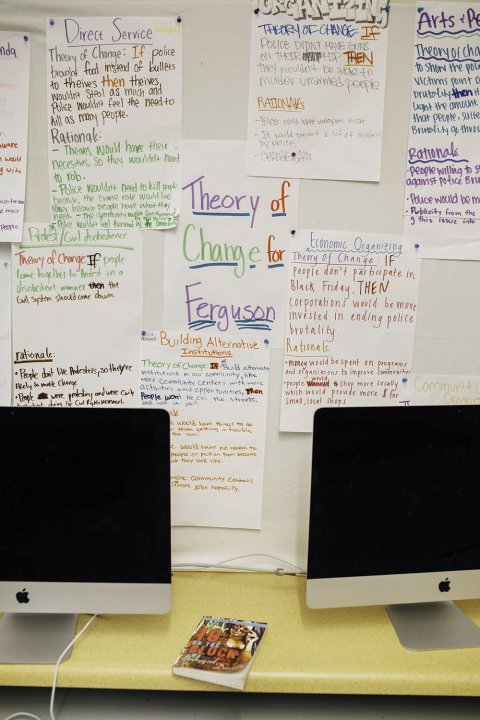

The MDP is engaged in an extremely tricky maneuver: first allow black boys to fully acknowledge the forces stacked against them, then convince them they can be successful in the very system that oppresses them. "Without a relationship, you can't push rigor," program director manager Jerome Gourdine, a former Oakland middle school principal, told me. Although the MPD is elective, it is a credit class, not some sparsely attended club held in a basement computer lab. Students may spend the period discussing the purported racism of law enforcement, after which they may head to a classroom where a white female teacher asks them to read My Ántonia and won't take "institutional racism" as an excuse when homework isn't done.

The program is, in some ways, a mixture of a history and English class, with a strong Afrocentric bent and a lot of time for personal reflection (there are actually two separate elective classes: "Mastering Our Cultural Identity" and "Revolutionary Literature"). Much of the class is focused on reflection and discussion. That is its main draw and biggest challenge. Fifteen-year-old boys of any race or creed are an intractable bunch. I was one once; I once taught many. They make up a naturally reticent demographic, not one whose members are ready to divulge their secret privations or to maturely confront social problems that have left entire presidential administrations helpless.

In an MDP class I saw at the MetWest High School, the students started class with push-ups, to get some physical energy out. They listened to a Bob Marley song and learned a Ghanaian word, zongo (" 'hood"). There was none of the chaos I so often witnessed (and sometimes unwittingly engendered) in various classrooms around New York City. The students were almost universally respectful. When they weren't, the teacher looked somberly at the offending student and said, "I need my respect." And he got it.

"This is a serious curriculum with rigor in it," says Baayan Bakari, an MDP program director, who explains that getting black students in the MDP class to read something like The Pact, a true account of three black young men who escaped the ghettoes of Newark, New Jersey, may prime them to tackle, say, The Catcher in the Rye in English class.

Part of the MDP's aim is to demonstrate to black boys that intellectualism isn't accessible only to whites. If you grow up in a two-parent household in Berkeley with regular trips to museums and libraries, with allusions to Daddy's college years and Mommy's favorite painting, you are so deeply inculcated with upper-middlebrow Euro-American culture that you probably don't even realize what a gift you've been given. But if you are from the projects, if you live with a mother who works nights at McDonald's, leaving you to cook dinner for your baby sister and put her to sleep, the notion of an evening spent with The Little Prince is almost offensively unrealistic. And by the time you're old enough to read, say, Pride and Prejudice, you've probably realized that some of the only black men on television are Lil Wayne, Marshawn Lynch and Michael Brown. To bother, now, with the demands of the white world would be totally pointless. Fuck that.

Chatmon stresses black achievement in the arts and sciences, and strives to kill the notion that street smarts trump book smarts. He acknowledges that the fruits of his labor "may not necessarily show up in a GPA." Not yet, at least.

Drugs and Guns and Young Women

Black girls do better in school than black boys, but they are subject to many of the same corrosive forces. Alas, there is no program for them, nor for Hispanic or Asian students who wage plenty of battles of their own. That means, according to NYU's Noguera, that the MDP can never have more than a "marginal impact." Noguera—who knows Chatmon and has been following the program—is quick to point out that Chatmon's work is "clearly beneficial." Nevertheless, it is not enough: "You can't solve this with a mentoring program."

Vajra Watson, a social scientist at U.C. Davis, is considerably more optimistic. Her report about the MDP is titled "The Black Sonrise"; as the unabashedly earnest title probably makes clear, she thinks the MDP is a hosanna-worthy triumph. Her statistics are slim comfort, however: a slight rise in GPAs, a modest improvement in reading capacity. And those may have come about only because the MDP selects motivated students. Yet, according to Watson, the MDP offers a crucial refuge for black boys. Asked to describe the experience of being young black men in America, they used words like hard, underappreciated, alone, mistreated and broke. As one student told Watson, MDP "made it cool to be black and smart."

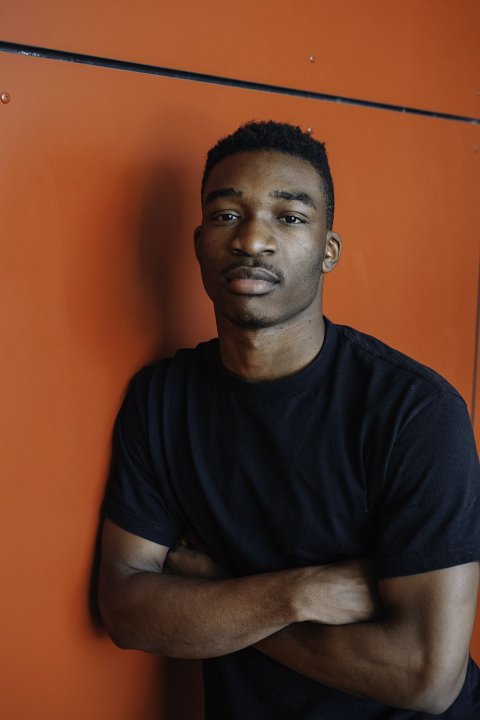

I met Toussaint Stone, 16, at the MPD offices, where he interns. He was wearing a Beavis & Butt-head T-shirt, though it is unclear if he has ever seen the show. The next day, he showed up in a T-shirt bearing the visage of Einstein. An 11th-grader at MetWest, he comes from the sump of crime and poverty that is East Oakland. He is thinking about going to a historically black college after he graduates from high school.

"We're basically the bad guys," he says of young black men. "We're the people they don't want to see in power." When I looked at his Twitter profile, I was struck by how much he looked like Michael Brown, wearing flat-brim hat, headphones, fingers curled into what the media would surely call a "gang sign," a hashtag proclaiming his affection for women with large behinds. You could easily, if you wanted to, see him as a thug.

Stone thinks that society is prejudiced against young black men but that young black men don't help their own cause. Many, he observes, have misplaced priorities: "drugs and guns and young women." His hero is Marcus Garvey, the Harlem Renaissance political thinker who advocated pulling away from a white America that would never relent in its racism. "I'm not saying let's all move to Africa," Stone told me, yet he was attracted by the message of black unity against adversities within and without.

I ask Stone if he can tell when a teacher doesn't care.

"Definitely."

I ask if he has had many such teachers.

"Definitely."

I ask why he joined the MPD.

"Because I am a black male in Oakland."

He does not need to explain.