Imagine that the death of a person you love is such a loss that the only way to stay sane is to transform yourself into the deceased. This is exactly what David (Romain Duris) decides to do when his wife Laura succumbs to a fatal illness. He dresses in her clothes, applies her make-up and walks around in a wig and high heels. "You're a pervert," diagnoses Laura's best friend Claire (Anaïs Demoustier), who is disgusted by him, at least at first.

Loosely following a short story by Ruth Rendell, French auteur François Ozon has crafted a smartly idiosyncratic tale. Yet The New Girlfriend begins with an elaborate test of one's patience, stringing together over-the-top clichés. Laura (Isild Le Besco) is lifted into a coffin, looking as pale and beautiful as Snow White. Then Claire delivers a teary eulogy, praising the dead friend and pledging that she will always look after Laura's husband and baby son. As if this wasn't enough faux melodrama, Ozon then adds flashbacks chronicling the origin of the two women's friendship. We learn that they played together as young girls, pledged blood sisterhood and, as young adults, married quite similarly nondescript men. Shortly after the birth of her son, Laura falls ill and, accompanied by Philippe Rombi's sickly-sweet score, exits this world.

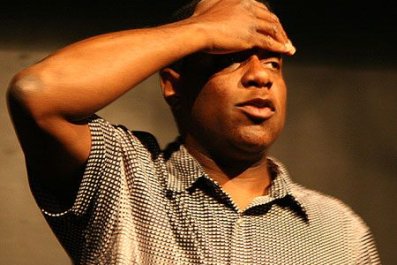

Fifteen minutes into the film, Ozon finally knocks over the tower of platitudes he has so carefully stacked up. Claire walks into the house where widower David lives. A strange blonde woman is bottle-feeding the baby. As "she" turns around, we recognise David, in full drag. "The baby cried for its mother, so I dressed up as her," he explains. Claire immediately senses that this is an excuse and that David is cross-dressing for his own gratification.

On one level she is repelled by his transformation into a transvestite but on another she can't help being attracted to him in this guise. In the course of the film, she becomes more and more estranged from her dull husband Gilles (Raphaël Personnaz) and drawn towards the man she now prefers to call "Virginia". Before one secret tête-à-tête, David asks her if she would prefer he appear as a man or as a woman. She picks "Virginia", who both fulfills the need of a female companion created by Laura's death and also triggers desires she had no idea she even had.

As the affair becomes steamier, Claire's angst about her feelings mounts. At one point, she makes up her mind to sleep with "Virginia" but panics when she realises what she knew all along – that her new girlfriend has a penis.

Ozon has crafted a fairytale with hairpin turns, revelling in its own improbability. He demonstrates that, in human sexuality, pretty much anything goes, even something as "perverted" as a transvestite who is attracted to women, and a woman who is attracted to transvestites. At first sight there is something touchingly anachronistic about this: why does Ozon even think it necessary to remind the audience that any form of consensual sex between adults is fine?

The inconvenient truth might be that the West likes to think of itself as permissive, but is becoming less so. For example, Ozon's home country France has just outlawed buying sex and other countries are heatedly debating where to draw the line between flirting and harassment. In the US, a software company is marketing an app that is supposed to ensure that people consent to having sex, making couples go through a five-minute checklist before their first kiss.

In certain quarters, there is a move towards reining in sexuality – something that, throughout history, has reliably failed. It is only a matter of time before today's teenagers – who are growing up with internet images of pretty much anything humanly possible – grow up and reverse the trend. In the meantime, Ozon remains cheerily defiant. He exposes the gap between how a seemingly "liberal" bourgeoisie likes to see itself and its actual sexual mores. Some critics were unconvinced by his recent effort Young & Beautiful, in which Ozon appeared to persuade the audience that it might, under certain circumstances, be all right for underage girls to prostitute themselves to older men. In The New Girlfriend his message comes in a more digestible form. The point he makes in both films is that sex never was, and never will be, politically correct; it feeds on transgression. Ozon has warned his audience to be prepared for their prejudices to be shattered. If they weren't willing to face the complexities and confusion of human sexuality, they should go back to the safe cartoon world of Hollywood.

Ever since François Ozon burst onto the international stage with Swimming Pool in 2003, he has been positioning himself as a French Fassbinder. His central interest in the confusion and unpredictability of sex is combined with a fondness for highly stylised form that puts him firmly in the tradition of the German auteur whom he acknowledges as his master. His and Fassbinder's capricious characters stay at a distance from the audience. As he has put it himself: "Some people go to the cinema to identify with the characters. Distance makes them afraid. But it's exactly that that I like about Fassbinder, his way of drawing back with the camera, of not sticking to the faces. Leaving the viewer the freedom to think."