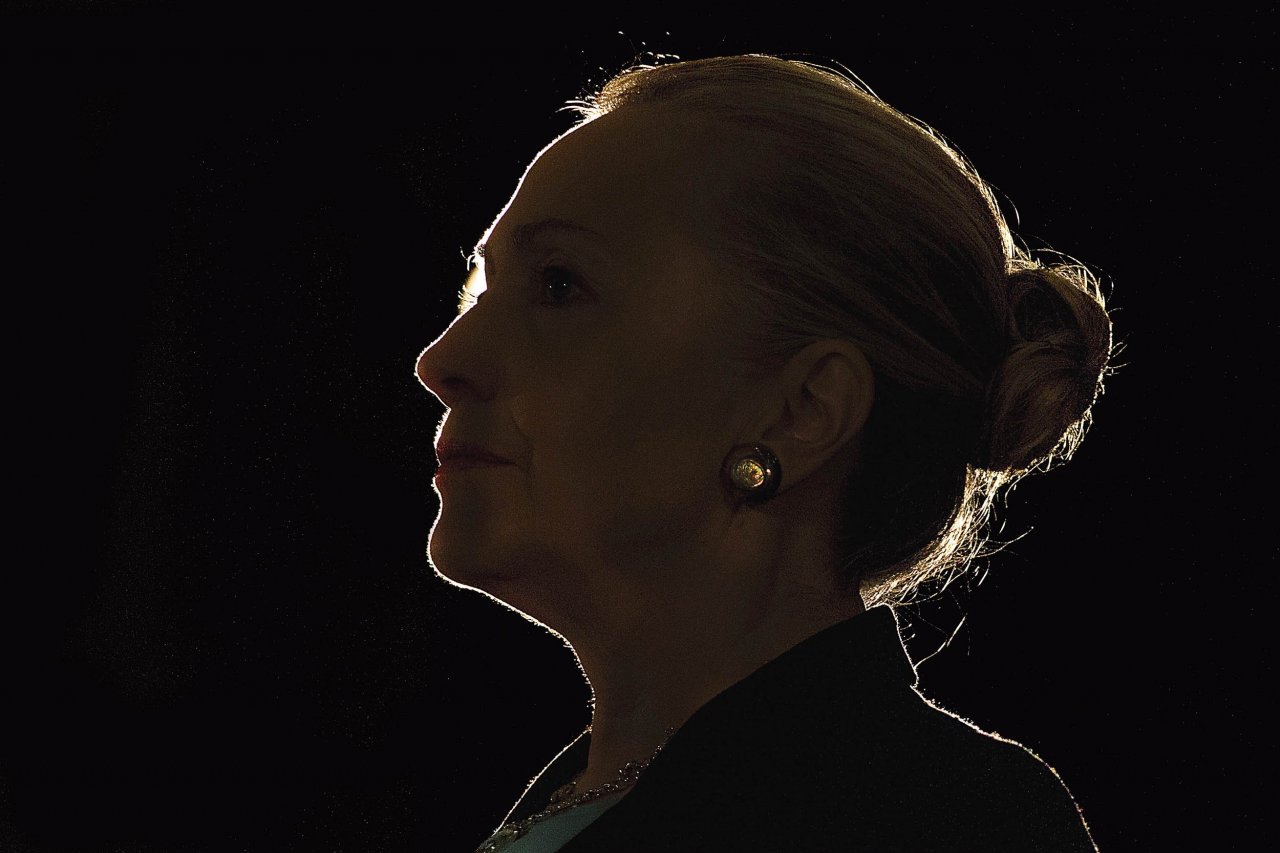

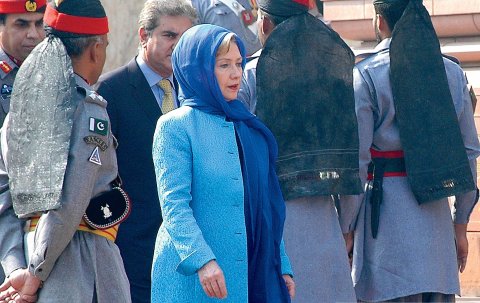

On October 28, 2009, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton arrived in Islamabad, Pakistan, for a three-day visit—without a headscarf. As the motorcade snaked through the city, Osama bin Laden was still hiding out with his wives less than an hour away, and Clinton was greeted with placards reading "Hillery [sic] Go Home." Shortly after she landed, a car bomb exploded in Peshawar, Pakistan, killing more than 100, and scenes of carnage were broadcast along with her televised welcome.

Traditionally when the boss rolls into town, U.S. embassies arrange a meeting with national leaders, a press conference and maybe a reception before escorting the secretary back to the tarmac. But Clinton had added a new duty: organizing the "Townterview." These awkwardly nicknamed, often televised gatherings with vetted natives reprised the town halls and "listening tours" that had been a hallmark of Clinton's style as first lady, U.S. senator and presidential candidate. The idea was to use her star power to rehabilitate America's image. "In an age of connectivity," Clinton policy aide Jake Sullivan explains, "even in authoritarian countries, public opinion matters. Hillary Clinton going out and reaching millions of people around the world through a give-and-take conversation, broadcast live, helped advance the sense that the United States is listening."

So embassy staff in Pakistan had arranged a small listening tour for Madame Secretary. Some aides had a bad feeling about the Townterview in Islamabad and a later one scheduled in Lahore. "They warned, 'You'll be a punching bag,'" Clinton wrote in her State Department memoir, Hard Choices. "I smiled and replied, 'Punch away.'"

Clinton got what she asked for when she faced female Pakistani journalists and an audience of professional women who had been told belatedly that they'd be participating in a televised format similar to The View. Whoopi and Babs they were not; they grilled Clinton, angered about what they saw as American designs on Pakistani nuclear power and U.S. support for archfoe India. Things got worse in Lahore, where university students asked about drones and trigger-happy American contractors. She nodded in her trademark way and crafted calibrated answers, but she won few hearts or minds.

The New York Times reported that in Lahore Clinton sounded "less like a diplomat and more like a marriage counselor." She did manage to land a punch, though, becoming the highest U.S. official to publicly accuse Pakistan of hiding the Al-Qaeda leader: "I find it hard to believe that nobody in your government knows where they are and couldn't get to them if they really wanted to."

The trip was not a seminal moment in Pakistani-American relations, but it typified Clinton's style as secretary of state in many ways: the good soldier taking a hit for the team; the career "listener" with unshakable faith in the power of her charm and reasonableness; the hawkish tendency; the innovative executive; the deft verbal strategist; and the star pupil who did the most homework and got a gold star from the teacher, in this case the White House.

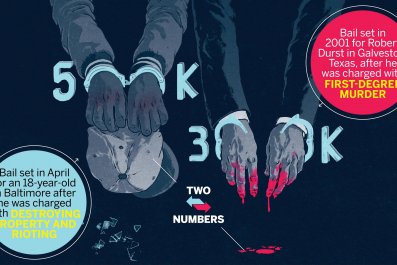

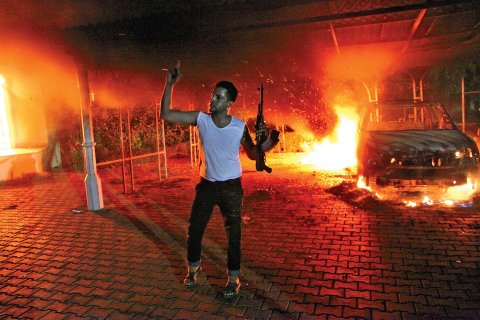

In Washington, despite the obsession on Benghazi (13 hearings and 25,000 pages of reports, at last count, on the killing of the U.S. ambassador and three other Americans; with her House committee testimony scheduled for mid-May), conventional wisdom holds that Secretary Clinton was good in her last job. She just left no legacy. "Competent" but "not a great one," wrote Michael Hirsh of her in Foreign Affairs, as she stepped down from the secretary's post in 2013.

Dismissing Clinton's performance at State as mediocre misses the point. Her great strengths—personal charm, innovative thinking, political savvy—were not up to the task of taming the likes of Putin, Assad, the Taliban, Boko Haram or the rest of the savage world in chaotic times. It's difficult to imagine any wise man now or in history—Henry Kissinger or Thomas Jefferson, to name two—being able to create order from a world in which a 1,000-year-old invention, the nation-state, is under siege everywhere.

The right question is whether Hillary did well with what she had, and the consensus answer is yes. Her policies sometimes fell short (the Russia reset, designed to improve relations with Moscow), but more often they were right (the Asia pivot to devote more U.S. attention to the Far East).

Critics often assume that to be a "great" secretary of state, a major diplomatic treaty must be crafted or a war ended. But modern secretaries of state are more managers than Metternichs—they don't necessarily have the grand visions of the world that the 19th century Austrian diplomat did. They confront foes and soothe friends and often they fail. Clinton was no exception, but her performance rating is of special interest now because her tenure at State reveals a lot about how she might operate as president.

LIKABLE ENOUGH

Clinton was the third woman to be secretary of state after Madeleine Albright and Condoleezza Rice. She sailed through her confirmation hearings promising to use "smart power," a wonky variation on "soft power," which was a too-girly-sounding strategy. Smart power implied a more equally distributed application of the military and the softer powers—diplomatic and development tools—than had been the norm in the George W. Bush years, when belligerent "military-think" predominated.

Clinton's job, as Barack Obama imagined it, was to win back some friends for America after the middle-finger stance of the W years. And according to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project, she did that. In 2008, America's overall favorability rating hit abysmal lows—in the 20s and 30s. By 2014, according to Pew, a global median of 65 percent had a positive opinion about America. Some of that was due to Bush leaving the White House and the hope invested in Obama, but some credit surely belongs to Clinton.

But her job was about more than refurbishing America's image. It was about managing relationships—with heads of state, with fellow Cabinet members (the State vs. Defense rivalry is one of Washington's oldest) and with Obama, not to mention the State Department's 70,000 careerists. It was her first run as an executive instead of a first lady, senator, law partner or chairwoman (of the Children's Defense Fund). Finally, she had to manage her relationship to power—for many women, the trickiest relationship of all.

She was a celebrity humbly serving a former rival in the Democratic presidential primaries who had once sneered that she was "likable enough." A popular Clinton caricature is the scheming Lady Macbeth. The meme was born during her husband's 1992 campaign and refreshed in the decidedly anti-Hillary best-seller about the 2008 primaries, Game Change, which gleefully detailed her profane meltdowns in contrast with no-drama Obama.

The giant egos vying for influence in the president's Cabinet, the vast bureaucracy of Foggy Bottom and the sprawling mess of global diplomacy all offered unlimited opportunities to hatch Machiavellian plots. And yet Clinton was a force for "teamwork and discipline" in the Cabinet, according to Obama. As secretary of state, Clinton logged nearly a million miles of air travel (956,733, to be exact), keeping healthy in body and spirit with Methodist prayers and yoga to deliver calm, and a tiny, talismanic bottle of hot sauce to ward off colds. During downtime she lived not with her husband in New York but in spinsterish isolation in Washington with her nonagenarian mother. "I'd come home from a long day at the Senate or State Department, slide in next to her at the small table in our breakfast nook, and let everything pour out," she recalled in her book.

Obama hoped having Clinton run the State Department would give him the space to devote his greatest energies to domestic matters like the passage of health care reform (something she had failed to do during her husband's time in the White House) and averting an economic depression. She took the job on the condition that he agree to meet regularly with her. Beyond that weekly face-to-face, they engaged two to three more times a week on the margins of larger White House meetings, says Sullivan, her aide. "They reinforced and supported one another." During a joint 60 Minutes interview in January 2013 after she resigned, CBS's Steve Kroft tried several times to get Clinton and Obama to reminisce about their political rivalry, but Obama wouldn't bite. Their friendship, he said, was based on "trust [from] being in the foxhole together."

THE SCHMOOZER

On February 10, 2010, Secretary Clinton and her entourage left the Snowmageddon of Washington, D.C., and landed a day later in the desert kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In the blinding sunlight on the tarmac, guards ushered her to King Abdullah's retrofitted bus, where she sat across from the foreign minister, Prince Saud al-Faisal, for a ride to the king's desert retreat. Inside a deluxe, black, six-top tent, she spent 20 minutes chatting with the 85-year-old king, teasing him about his foreign minister's dislike of camels. After a requisite feast, she and the king retreated for a four-hour private meeting from which she emerged "smiling broadly." She soothed ire over Obama's prior visit to the kingdom, during which he had turned to unpleasantries immediately—asking the king to allow El Al to fly over Saudi territory and for him to receive Israeli trade ministers. It had been all too fast and too much for the ancient Arab potentate. "Whoever advised you to ask me this wants to destroy the Saudi-American relationship," the king supposedly said.

In Hard Choices, Clinton recounted how she put her friendship with the Saudi leadership to use. Rights groups were outraged that a 50-year-old Saudi man was about to marry an 8-year-old girl—an act the child's mother opposed but was legal in Riyadh. Saudi courts had rejected the mother's plea to stop the marriage. Clinton quietly intervened by phone. "Fix this on your own, and I won't say a word," she recalled saying to the Saudi authorities. A new judge was appointed, and he granted the child a quickie divorce.

She used the same personal touch behind the scenes with former Afghan President Hamid Karzai, an ally who had gone rogue, double-crossed Obama and was enmeshed in corruption. "Of all the leading members of the national security team, she had the best ability to talk Karzai down," a former spokesperson at State tells Newsweek. "He is prone to say these crazy things, and she would be the one periodically that would pull him off the ceiling. She would say, 'Look, Mr. President, I understand you have all these competing constituencies. Let's try to figure out a solution that works within the context of your politics." Clinton, the politician, understood the needs of other pols.

She used the same combination of patience, empathy and celebrity that had won over a thobe-draped Saudi potentate and the notoriously difficult Afghan president when confronting one of the greatest crises in the State Department's internal history.

Just before Thanksgiving 2010, newspapers were preparing to publish excerpts from classified documents released by WikiLeaks, including thousands of diplomatic cables in which far-flung U.S. officials had regaled Washington with candid critiques of world leaders. French President Nicolas Sarkozy was described as an "emperor less than fully dressed"; Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu was "lost in neo-Ottoman Islamist fantasies"; Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd was "a mistake-prone control freak." Clinton was on record saying Saudi donors were "the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide" and complaining that it was "an ongoing challenge" to get Saudi leaders to address the problem. The remark was ironic because the Saudis were among the biggest donors—tens of millions of dollars—to her husband's Clinton Global Initiative (now called the Clinton Family Foundation).

Today, although WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange is still holed up in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London and Chelsea Manning, the soldier-whistleblower, is in jail, WikiLeaks is basically a blip in the annals of State Department history. At the time, it was such a crisis that some speculated Clinton would have to resign as an act of national contrition.

Instead, she got on the phone. After a long Thanksgiving weekend spent making hundreds of personal apology calls, she had already done private damage control by the time WikiLeaks dropped its bomb on Monday morning. Clinton's personal relationships and exhausting display of contrition maintained trust between national leaders after the first great leak of the cyberage. The episode also positioned her as a battle-hardened government loyalist when Edward Snowden's revelations about the National Security Agency peeled back the veil on the vast American cyberspying apparatus.

THE MANAGER

Former Bush and Reagan diplomat Elliott Abrams, a leading neoconservative, thinks Clinton was terrible on the Arab Spring movement and left no worthy legacy. Still, he gives her high marks for management. "Morale in the State Department was very high" under Clinton, he says. "She surrounded herself with some very able young people."

One of her first administrative acts was to launch the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR), modeled on the Pentagon's Quadrennial Defense Review, aimed at modernizing the structure of the State Department. The first QDDR focused the department on emerging areas such as post-conflict resolution and the cyberworld. She created an office for public-private partnerships and community outreach, and promulgated a manual for the ethical and legal policy rules for such partnerships.

In the hive of the Building—as State Department hands call the eight-story Foggy Bottom headquarters, with its 4,975 rooms—Clinton was queen bee. But she was also the busiest worker bee, ensconced in her elegant seventh-floor office with fireplace, Oriental carpet and soft homey chairs, reading briefing books no one else opened and perpetually scratching items off her legendary checklist. (One adviser believes she was the only top official to actually slog through the briefing books.) It was the same studiousness that had earned her plaudits in the Senate when many expected her to be a show horse.

At State, Clinton reassembled some of her now familiar entourage. It was Hillaryland redux—personal aide Huma Abedin, who endured the tawdry Twitter exhibitionism of her husband, Anthony Weiner; politico Philippe Reines; and Cheryl Mills, the infamously protective former deputy White House counsel, who defended Bill Clinton during his impeachment trial. But she also tapped new brains, including Sullivan, who recalls that Clinton insisted upon hearing from people outside the chain of command. During one early meeting on the issue of Muslim extremists in Europe, Sullivan says a George W. Bush holdover, regional expert Farah Pandith, spoke up about how extremism was affecting communities. Clinton, who had not previously met Pandith, quickly made her the State Department's first-ever special representative for Muslim communities.

"That's the kind of thing that would happen [often]," Sullivan says. "She would say...'I want to hear people speak up and disagree.'"

IDEALISTIC REALIST

Clinton could charm, but she could also make cold calculations about how much of her resources to expend. "Our challenge is to be clear-eyed about the world as it is without losing sight of the world as we want it to become," she wrote. "I prefer being considered…an idealistic realist. Because I, like our country, embody both tendencies."

She was more mechanic than messianic, and she harbored no Wilsonian- or W-like schemes to make the world safe for democracy. One country in which she applied her measured approach was Hungary.

In 2010, Hungarians elected a rightist party, Fidesz, that immediately set about writing a new constitution, shackling the media and restricting opposition parties and civil society. The anti-democratic trend was more than a far-off concern because Hungary was about to take its turn at the helm of the E.U. presidency in 2011. And it was alarming because the country was a NATO member that had been on a democratic path and now seemed to be drifting into Moscow's orbit.

Clinton traveled to Hungary in June 2011, intending to share American concerns. As was her custom, she asked the embassy to gather members of civil society groups for a meeting. Ambassador Eleni Kounalakis and her staff arranged to bring in Hungarian journalists, lawyers and rights activists, who talked about how they had been systematically shut out of national decision making. "Secretary Clinton listened intently," Kounalakis recalls. "Then she asked the group what they were going to do about it."

The democratic-minded Hungarians were stunned. The sympathetic, nodding face of the superpower had raised their hopes that the Americans might take a robust role in supporting their cause. (The failure of the Eisenhower administration to support the anti-Communist Hungarian uprising in 1956 is still remembered in Budapest.) Now Clinton was telling them they were still on their own. It was a "sobering and powerful" message, Kounalakis says, meant to prod the Hungarians to fight back.

Later that year, the Hungarian parliament passed anti-democratic measures without the input of civil society groups or opposition parties by a two-thirds vote. Clinton dove back in, with a letter to Hungarian President Viktor Orban detailing U.S. concerns. The letter was leaked, and "headlines roared of the specific concerns that Hillary Clinton and the United States were expressing over Hungarian democracy," Kounalakis wrote in a memoir about her years in Hungary. The gambit worked, and belatedly, European leaders and EU officials who had ignored the situation began speaking out about the Hungarian laws.

Weeks later, Hungary's leaders announced they had "moved too fast" and needed to "make corrections" in the oppressive laws.

That small victory for Clinton was short-lived. A new Hungarian president was installed and soon implemented many of the offending laws: diminishing women's rights, condemning homosexuality and putting the central bank under political authority. Today, anti-Semitism is on the rise, and The Guardian spoke for many when it announced: "Hungary is no longer a democracy."

Clinton's modest efforts in Hungary only delayed the inevitable. "Under ordinary diplomatic constraints she did as much as she could very effectively," Kounalakis says. "I am convinced that her leadership and engagement brought positive change to that country. But, as a realist, there is a limit to U.S. engagement in the internal affairs of a NATO ally."

Clinton used soft power and personal clout to help push back on an authoritarian regime. It didn't work, but it seems unlikely that any secretary of state would have had better luck. The U.S. was no more willing to use force than Eisenhower was almost 60 years ago, and there was no support from allies for sanctions. The episode illuminates the limits of U.S. power in the 21st century, and it shows Clinton doing the best she could with a very weak hand.

THE HAWK

Last year, Mother Jones published a column titled "Who Said It?" that challenged readers to figure out which hawkish statements were uttered by Hillary Clinton and which came from Republican Senator John McCain. Progressives suspect Clinton has neocon in her veins because of her vote to authorize the use of force in Iraq. They're probably right. She doesn't share McCain's dismay at the withdrawal of American troops in Iraq on her watch, but as secretary she was rarely, if ever, the dove in the room.

This became apparent when it came to Libya, long before the notorious 2012 Benghazi attack. The Libya crisis escalated from unrest into civil war during March 2011. The Arab Spring had come to Libya, and its leader, Muammar Qaddafi, had vowed to exterminate his opponents. With a humanitarian disaster looming, the sentiment in the West was swinging toward intervention.

By the time Clinton landed in Paris on March 14 for a meeting of the G-8, even Arab League members were calling for "robust" action in Libya, and Sarkozy was all but brandishing a sword. Clinton sided with two other Obama national security counselors, Samantha Power and Susan Rice, in supporting military intervention for humanitarian reasons. Pundits took to calling them "the three Valkyries," but in Paris she was in no rush to send bombs over Tripoli, reflecting the mood in Obama's situation room. "I was sympathetic but not convinced," she later wrote.

Then the Arab League voted to request a no-fly zone over Libya. As terrified Libyan civilians waited for Qaddafi to start his slaughter, Sarkozy dispatched French warplanes to Libya without conferring with the British or Americans. After that, Clinton wrote, "there was no time for hesitation." A few hours later, U.S. Navy warships fired more than 100 cruise missiles at Libyan air defenses and ground troops.

Critics blamed America's reluctance to bomb on a strategy—or lack of one—that came to be called "leading from behind." Clinton denies that: "It took a great deal of leading—from the front, the side, and every other direction—to authorize and accomplish the mission and to prevent what might have been the loss of tens of thousands of lives."

Fair enough, but her willingness to use force in Libya—and her later eagerness to arm Syrian rebels—makes her complicit in the at best confused, and at worst failed, American response to the Arab uprisings. The attacks in Libya left that country in chaos and open to colonization by North African Islamists, and created the current refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. Clinton might not be another McCain, but she is a liberal hawk, convinced that bombs can be humanitarian. And though NATO airstrikes may have brought an end to Serbian oppression during her husband's presidency, in this century good intentions have not often been rewarded. Like George W. Bush, she promoted U.S. military action that left a repressive Arab country in anarchy.

HALF THE POPULATION

In 1995, Clinton became the first representative of a superpower to equate women's rights with human rights, a seminal moment that made her a hero to women worldwide. It put the world on notice that if you beat your wife or denied your daughter an education, it was no longer a private matter.

One of her first acts at the State Department was to appoint her White House chief of staff, Melanne Verveer, as ambassador-at-large for women's issues. "My role…was not to oversee 'special projects,'" says Verveer, who has been with Clinton since 1997. "It was to play an integrationist role, so [women's] issues would be integrated throughout the State Department."

Verveer tells Newsweek her chief achievement was collecting and disseminating data to other nations on how women's involvement affects economies favorably: "Data shows women's participation creates jobs and influences security. No country doesn't want to grow its economy." Other high-profile women's initiatives included a public-private project (in alliance with the Clinton Global Initiative) to bring cookstoves to women in poverty-stricken areas. On the policy side, Clinton persuaded Obama to sign a National Action Plan that put the U.S. behind a long-standing U.N. resolution to involve more women in conflict resolution, peace and security.

With Verveer dispatched around the globe to talk about women, Clinton could be a feminist without getting on a soapbox. She rarely spoke out publicly, for example, about the egregious mistreatment of women by America's allies in the Gulf. For human rights observers, that reticence was a signal flaw, but her colleagues say her feminist instincts are unassailable. "We all know successful women who wouldn't go near a woman's issue because that detracts from her ability to play in the big leagues," Verveer says. "Well, Hillary understands you can't write off half the population in the world."

BLOOD THINNERS

Coming home after long days grappling with apocalyptic global mayhem, Clinton relied not on her husband but on her aged mother to help her unwind. Dorothy Rodham's death in November 2011 left Clinton alone, and the pace eventually took a physical toll.

"The exhaustion is always there," says Verveer. "These are killer jobs, very hard jobs, especially if you do them in intensive ways." Clinton had walked into State exuding energy, and crawled out four years later, straight into a hospital. She fell and smacked her head during a woozy episode in what was reportedly a bout with a stomach virus in late 2012. The accident left her with a dangerous blood clot behind the right ear, requiring hospital observation and a regimen of blood thinners.

She no longer has to tangle with Putin or Karzai. Now she faces angry investigative committees. But she's been here before. Committees have come and gone, from Whitewater to impeachment, and she's still around.

Whatever happens to her presidential bid, the years at State seem to have released her from the defensive crouch she maintained during her first lady years. Verveer says Clinton has evolved into a happier person. "When we first got to know each other, she was in a position solely by virtue of her marriage. How many times did you hear people say, 'Who elected her?'"

Stints as first lady in Arkansas and the White House are not a good launch pad for any modern politician, but Clinton captured a U.S. Senate seat in 2000 with a lot more than her last name. Based on résumé alone, Hillary Clinton is arguably more qualified to run the White House than her husband was when he got elected president in 1992. In terms of job training, 14 years as governor of Arkansas do not match eight years in the White House (granted, as a spouse), six in the Senate and four traveling the globe as secretary of state during one of the most chaotic eras in memory.

Early in American history, secretary of state was a steppingstone to the presidency. Jefferson was among six men to use it as a rung, but it has been 160 years since the nation's top diplomat was elected president. On our fractious and yet hyper-connected planet, where events in Pakistan reverberate in New York City, a stint at State ought to be a résumé builder for the presidency, but as former National Security Council spokesman Tommy Vietor said to Foreign Policy recently, "I do believe that not a single voter will make their decision based on her policy towards Burma. You'll be lucky if they know where the fuck it is." Historian Douglas Brinkley put it more politely: "You've got to play big in Des Moines, not in Paris."

Clinton's time at State proved the professional "listener" can also make men listen. Obama affirmed that when he said on 60 Minutes, "One thing I will always be grateful for" was Clinton's way with big egos. "We had [Defense Secretary] Bob Gates and [CIA Director] Leon Panetta and a lot of strong personalities around the table," he said, noting she had "established a standard in terms of professionalism and teamwork." Gates, who served in both Bush administrations, was even more effusive in his praise: "I found her smart, idealistic but pragmatic, tough-minded, indefatigable, funny, a very valuable colleague, and a superb representative of the United States all over the world."

Beyond the Beltway, Clinton's stint as America's top diplomat earned her other sorts of devoted fans. Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt, who is backing her campaign, has called Clinton "the most consequential secretary of state since Dean Acheson."

Sullivan, Clinton's aide, who admits he is a fan (he also might become the youngest national security adviser in history if she's elected), calls her relationship with the men in Obama's Cabinet "a high-water mark" of her term at State. "People leaned forward when she spoke," he says. For a woman working in rooms full of men, there is perhaps no higher praise.