From here on, if you're going to riot, you'll probably want to wear those funny nose glasses. And maybe a wig. Because otherwise facial recognition technology is going to land you in the clink.

This is not just some Kim Jong Un wet dream about a police state no one can escape. A trio of technologies—computer learning, social networks and cameras everywhere—are converging to make it possible to identify rioters and looters after the fact. It will have much broader implications too, since the technology will identify almost anybody anywhere doing anything. No more surreptitiously wandering into Adult Playland for you, mister.

Early versions of this technology have already been deployed to help police arrest rioters in the U.K. and in Vancouver, where things turned ugly in 2011, when the only thing that can make people in Canada riot happened: The city's team lost a hockey game.

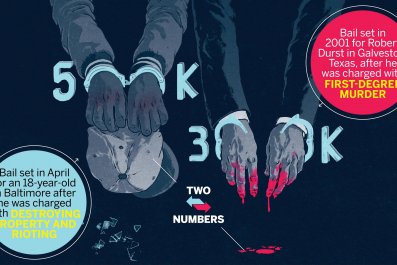

Amazingly, we haven't heard much about Baltimore using this technology in the aftermath of the riots there, even though the mayor, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, kind of said they would. So far, Baltimore police have reported just one incident that foreshadows future tactics. When a young man slashed firefighters' hoses as they tried to put out the blaze at the CVS, someone caught the act on a cellphone video and posted it to social media, where someone else saw it and tipped off police, who then arrested and charged 22-year-old Greg Bailey. But that's more about Bailey's bad luck than a strategic new way to keep the peace.

However, that's going to change, and the first trend driving this change is the ubiquity of cameras. There are about 7 billion cellphones in the world, pretty much one for every person, and almost all those phones have cameras. In TV news footage from Baltimore, rioters could be seen taking cellphone images as casually as if they were on vacation at Disney World. Of course, cellphones have also caught police brutality, and footage of the arrest of Freddie Gray set off the riots in Baltimore. As Jon Stewart cracked on his show: "The ubiquity of cellphones is far outpacing police awareness of the ubiquity of cellphones."

The number of surveillance cameras is also exploding. They've been in banks and lobbies for ages, but as the cost of cameras and image storage plummets, the technology is finding its way into every small business and a lot of private homes. One guy in Colorado set up a cam so you can watch his grass grow. Basically, you now have to assume that someone could be taking images of you any time you're in public.

So what happens to those images? Well, a lot of them get uploaded to social media, where the whole wide world can see them. Facebook is the largest repository of photos in history. Its 1.4 billion users upload 300 million photos a day. And then there's video. YouTube alone has 1 billion users, who upload 300 hours of video every minute. That means every minute of actual reality equals 18,000 minutes of YouTube reality. Try to think that through next time you're stoned.

Those two developments are already changing the way police find criminals. After the London riots in 2011, police created a Flickr page, "London Disorder – Operation Withern," and posted images of looting and violence, asking the public to identify the alleged perpetrators. There were about 5,000 arrests with help from the site. And yet, asking for that kind of help from the public is like making copies of a book by hand just as the printing press is being invented.

Facial recognition software has come a long way quickly. We've all helped it greatly just by posting and tagging photos on Facebook. That has created a lot of photos that help computers learn about how a face can look different depending on the angle, lighting, expression, age and so on. And a Facebook project called DeepFace has been systematically teaching computers about faces. At this point, DeepFace correctly identifies a face about 97 percent of the time. When humans look at photos, they get it right 98 percent of the time. So if you're a criminal and you've ever had a photo of yourself posted on Facebook, you're hosed.

Facebook isn't the only entity racing to develop facial recognition. The U.S. intelligence research arm last year started up a facial recognition project called Janus. In the police world, NEC Corporation of America (parent company of NeoFace) and other companies are marketing technology that can match the mug shots in a police database with images caught on security cameras or posted on social media. Other companies are selling facial recognition to retailers, which might use it to spy on known shoplifters.

Some of this is even getting silly. Microsoft made a splash recently when it turned its facial recognition software into a website that can estimate a person's age. This could be quite useful to anyone using a dating site.

The flip side, of course, is the creepiness factor. It's easy to imagine abuses, especially by governments that aren't all that thrilled about freedom of speech and action. As is the case with almost every aspect of our digital age, we're going to have to either adjust our expectations for privacy or pass laws that govern this stuff.

Not everything about facial recognition is police-state-oriented. Facebook has said that it wants to use DeepFace to protect privacy, not invade it. The software will sense any time a photo of you is uploaded by anyone and give you a chance to blur your face. Retail operations are interested, as a way to improve customer service. Perhaps a system could recognize you as you come in the door, alerting employees so they greet you by name and anticipate what you want, the way it might happen in a small-town shop you go into every week.

And think of the embarrassment saved if you were to wear a Google Glass type of device to a company party and it can recognize the guy in Accounting you should know and tell you his name.

Still, security and policing are a big driver of facial recognition technology, and every society is going to have to figure out how to balance this with human rights. People are already starting to push back. One British designer, Adam Harvey, hosted a recent session on hair and makeup techniques aimed at defeating facial recognition software. Although, really, nose glasses should work just as well.