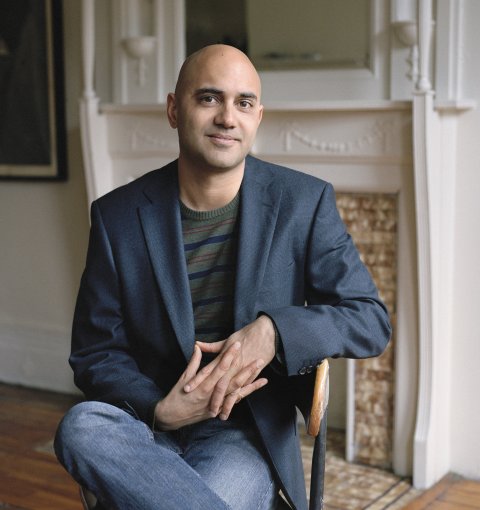

It's a story he's dined out on many times. In March 2012, Pakistani-American author and playwright Ayad Akhtar was doing his first big Q&A, with Chicago Tribune theater critic Chris Jones at an event sponsored by the paper. Akhtar's first novel, American Dervish, had just been published to rapturous reviews, and Chicago's American Theater Company was staging the first production of his play Disgraced, which would go on to a Broadway run and a Pulitzer Prize the following year. Both novel and play deal with issues of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, and both feature Pakistani-American men behaving badly: drinking, cheating, beating their wives and taking the name of every lord in vain.

"In the front row were a line of Pakistani-American mothers," Akhtar recalls. "They're all lined up, looking at me askance, arms crossed. At the very end of the interview, one of them raised her hand and said, 'We all drove in from the suburbs. We all read your book for our book club. None of us are going to speak to you except for me. And I just want to tell you that we need to understand what it is we need to do so that our children don't turn out like you.'"

It certainly wasn't the first time an artist had been reviled by his own people, and the 44-year-old Akhtar has been at the top of the list of important Muslim-American authors long enough to be something of a target. Jones deftly deflected her question by recalling the reaction Philip Roth received for his early books (Goodbye, Columbus; Portnoy's Complaint) from some older Jewish readers.

"Roth broke ground for me," says Akhtar. We are having iced tea near Lincoln Center, where Disgraced had its New York City debut. "I was reading Roth, [Saul] Bellow, Chaim Potok, watching Woody Allen, watching Seinfeld. Those were the artists who made me understand, Oh, this is how I can write about my community, which is an American community but also an ethnic community. It's a religious identity, and it's one that has its own aesthetics and its own humor and textures….Potok was writing about Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn, and I remember reading him as a teenager and thinking, I'm reading about my own people. I know these people. I see them every weekend. They're Muslims in Milwaukee, but they might as well be Hasidim."

Disgraced (which opens at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre in California on November 6) will be the most produced play in the U.S. this coming season, and the playwright says there will be more than 50 productions over the next two years—eight in Germany alone. That puts Akhtar in Arthur Miller territory, the sort of comparison he's quick to deflect. "It's an easy play to put up. It's a single set; it's five characters; it's multicultural," he says by way of explaining the play's seeming universal appeal. "It makes a case that is exciting to theatergoers, but it's also serving [the theaters'] diversity initiatives. When it's done well, it's a play that delivers a lot of laughs and then a gut-punch, so audiences feel like they've been satisfied even if they're confused."

Disgraced falls into a category that might be called the Exploding Dinner Party Play: As with Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and God of Carnage, these stories portray a civilized soiree that turns schizo, and nice, educated people who start screaming at one another as the La Tur softens on the cheese plate. Except the subtext here is Islam. The character of Amir is a Pakistani-American lawyer working for a Jewish firm in New York whose life starts to unravel after he reluctantly lends his name (and not even his real name) to the cause of an imam accused of terrorism. His wife, Emily, is a painter drawing on Islamic imagery in her work, and on the evening at the center of the play's action, the couple hosts a Jewish curator (who is interested in more than Emily's painting) from the Whitney Museum of American Art and his wife, an African-American woman who is employed at the same firm as Amir.

With the application of much booze come accusations of infidelity, a debate on political correctness and a not-entirely-uninformed discussion of Amir's erstwhile faith, with the roles somewhat reversed. "Islam is rich and universal," says Isaac, the curator. "Part of a spiritual and artistic heritage we can all draw from."

For Amir, the Koran is "like one long hate-mail letter to humanity"—though he admits to having felt some pride on September 11. And that's before things get really ugly.

"I think the play is seductive," says Akhtar. "When it's done well, it makes you think that you're smarter than you really are." He laughs. "It certainly makes me look smarter than I am! I think there are folks who would say—and I don't disagree with them—that there's something dangerous about this play going all over the country."

"No one's writing this [kind of] play," says Disgraced director Kimberly Senior. "It's not the moody sentimentalism that I think is plaguing theater. Things have gotten very twee, soft and precious. And in walks Ayad with this muscular, sexy, exciting writing."

Akhtar is now adapting the play for HBO ("I've broken it up into four parts, so you're much better set up for the intricacies of what happens on that evening") and is hard at work on his second novel. "It's a saga of a lot of what's happened in the Muslim community since 9/11," he says.

His first published novel, American Dervish, is a coming-of-age story about Hayat, the only child of Pakistani parents, growing up in Milwaukee, grappling with Islam and anti-Semitism and crushing hard on his mother's best friend. It was not the first book Akhtar wrote, however. The Columbia graduate (he studied film there and later theater at Brown) spent years on a "600-page attempt to rewrite Fernando Pessoa's Book of Disquiet, [filled with] plotless philosophical meditations on the machinations of the market"—a novel, in other words, that no one wanted to publish, let alone read—before awakening to the rich material that had been before him all along. "I tried to be the kind of writer I could never be for a good 15 years before stumbling into my own subject matter by realizing I had been avoiding it all along," he says. It was 2006, his marriage of 10 years was falling apart, and he was having the sort of spiritual-artistic crisis that he tries to describe by paraphrasing Kierkegaard: "Someday, the circumstances of your life will tighten upon you like screws on a rack and force what's truly inside you to come out."

He wrote American Dervish in a fever. The book was published in January 2012, and the reviews were ecstatic. "What distinguishes Mr. Akhtar's novel is its generosity and its willingness to embrace the contradictions of its memorably idiosyncratic characters and the society they inhabit," wrote Adam Langer in The New York Times. Many Muslim readers were not so enthused.

"On Page 2, Hayat eats sausage, and 40 percent of Muslim readers put the book down," Akhtar says. "'Why would I read a book about a guy who eats sausage? I don't have anything to learn from this guy!'" (At least the aunties who came to the Chicago interview had read the book.)

How did Akhtar's parents, the inspiration for Hayat's fictional family in American Dervish, feel about the book? "I have every suspicion that my father has not read the book," he says. (His father, like the fictional one, is a successful doctor who claims never to have read a book.) "My mother, on the other hand, read it very quickly a few months before it was published, and she called me and said, 'I want to talk about something, and I never want to talk about it again. I was very happy to see you understood that everyone was doing the best they could.' I said, 'That's beautiful, Mom, thank you.' She said, 'I don't want to talk about it anymore.'"

When asked if he regards himself as a Muslim, the author—who, like Hayat in American Dervish, had an Islamic immersion experience in his early teens that reading Dostoyevsky in high school uprooted—says, "I take a lead from my smart Jewish friends and say I identify as a cultural Muslim. Which means I feel informed and formed by the ethos and mythos and the mind-set and the spirituality of the Muslim tradition, without believing in the literal truth of any of its tenets."

Such talk might not get him off the hook with some Muslim readers and theatergoers. Akhtar lists among his influences Salman Rushdie (no problems there!), and by criticizing the religion of his people and even invoking the Prophet Muhammad (who is discussed, though not represented, in another of Akhtar's plays, The Who and the What), he's courting controversy. The Goodman Theatre in Chicago invited a Muslim scholar to offer feedback to the cast when it staged Disgraced and was surprised when the scholar tore into it and the play.

"If [Jean] Genet was doing Our Lady of the Flowers, would you invite a priest?" Akhtar asks.

"I think what the play can teach is that there is no such thing as a monolithic idea of what a Muslim is," says director Senior, whose background is Syrian-Jewish. "Amir doesn't represent all Muslims. He's one man. In fact, he calls himself an apostate."

For Akhtar, the message is not confined to anyone grappling with one faith, one community. He recalls reading from his novel at the Tattered Cover bookstore in Denver and meeting a young man who had driven 150 miles to hear him. "He came up to me afterwards and said, 'I grew up in Indiana in a Pentecostal house; your book is the best book I've ever read about what it's like to try and leave a community.' He was gay, and he wept as he was hugging me. And I thought, That's what the book is about. It's about the experience of losing your religion, losing your community, but still feeling connected to that past and those people. Still being filled with love for it but feeling separate from it. That's the story I was trying to tell."

Disgraced will have its West Coast premiere at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre November 6 through December 20.