Florida's self-proclaimed Queen of Semen is a diminutive 41-year-old with two advanced degrees and a biweekly appointment with elephant penises. "My parents don't really understand what I do," says Wendy Kiso, a research and conservation scientist at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Center for Elephant Conservation (CEC) in Polk City, Florida. "We just don't discuss it."

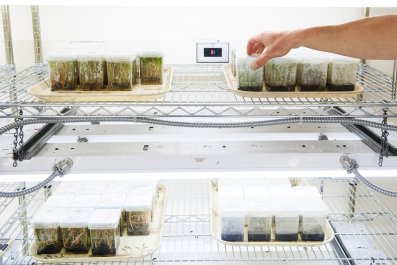

What goes unsaid in the Kiso household is routine small talk at the CEC, where Kiso specializes in the endangered Asian elephant and, more specifically, semen biology, storage and cryopreservation. Established in 1995, the 200-acre center is home to the largest herd of Asian elephants in the Western Hemisphere, some 28 pachyderms aged 2 to 70. Twenty-six elephant calves have been born here, including Barack, the now 6-year-old male who was the first CEC elephant conceived using artificial insemination.

Funded by Ringling, the CEC houses elephants who are training to perform or have already retired, as well as some who will never see the inside of a circus tent, either by virtue of temperament or timing. In March, after years of public outcry, Ringling parent company Feld Entertainment announced it would be retiring all of its performing elephants by 2018. Those still on tour will find their way to Polk City over the next two years, bringing the center's population to 42.

Related: Why Elephants Don't Get Cancer

At the CEC, elephants are grouped into "socially compatible" crews—2-year-old Mike hangs out with Baby and Rudy, who look on languidly as Mike gets himself stuck in a tractor tire. A few fields away lounge Mysore and Sara, the old biddies of the group. (At 70, Mysore is one of the oldest Asian elephants in the country.) In their own pens—male elephants are loners in the wild as well—are P.T. and Gunther. As Gunther uses his trunk to toss sand in our general direction, Janice Aria, director of animal stewardship at Ringling, who joined the company in the 1970s as a clown, tells me how he broke two of his balls standing on them. It takes me a minute to realize she's talking about the large rubber ones in his pen.

It's an honest mistake. Within 10 minutes of my meeting Aria and Kiso, we've talked about when the male elephants' sperm is collected (every Tuesday and Thursday), and Kiso has confessed that she can identify any of the CEC's elephants by penis alone. The only bodily discharge more commonly discussed is feces, as the CEC in many ways revolves around the constant disposal of enormous amounts of it. Aria shows me the main barn's "poop trench" and bemoans its $8,000-a-week disposal bill. On the train cars used to transport the elephants to and from the center—and between circuses—urine and excrement are bagged and removed by a trainer whose seating compartment looks out exclusively on elephant asses.

Indeed, the workaday to-do list for the CEC's 18 staffers reads like that of a new parent, and the employees discuss their two-dozen charges with the same mix of awe, affection and exhaustion that characterizes infant care—though at a cost Feld puts at $65,000 per year per elephant. There are eating schedules and bathing schedules to track, and poop regularity and nap habits to document. The staffers know the idiosyncrasies of each elephant (Mike hates sandy carrots; Mysore won't wear a blanket), as well as who doesn't like whom and which elephant buddies are currently on the outs.

Not that the elephants' social habits are trivial: The CEC parses the herd into cliques in part to sidestep what it considers nature's indifference to cruelty. Just a few football fields away from Mike lives his 19-year-old mother, Angelica; in the other direction, both of his grandmothers share a pen. One might think there is an occasional family reunion, but they never interact: CEC staffers separated Mike from his mother over concerns that his budding tusks might hurt her. While male elephants separate from their mothers in the wild as well (females not so much), it usually happens after age 10.

The weaning of calves from their mothers has sparked outcry from activists like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), as have Ringling elephants' intense circus schedules and the CEC's lackluster attempt to replicate their natural habitat (the center is primarily sparse fields, sandy expanses and clean but austere barns, where the elephants are still tethered by ankle chain at night). In November 2011, Feld paid $270,000 to settle allegations from the U.S. Department of Agriculture that it had violated federal animal-welfare laws, the largest civil penalty ever assessed against an animal exhibitor under the Animal Welfare Act. That same month, Mother Jones published a yearlong investigation titled "The Cruelest Show on Earth," which alleged systemic barbarism in the way Ringling treats elephants on the road and at the CEC.

Stephen Payne, Feld's vice president of communications, says the company "disagrees vehemently" with Mother Jones's conclusions. "We are not proponents of animals' rights, but we are the first proponents of animal welfare. We have a responsibility to care for these animals for their entire lives."

The legal controversy seemed to come to a head last year, when animals rights groups were forced to pay $16 million after it emerged that they bribed a former Ringling employee to say the circus was mistreating its elephants. But the PR battle was already lost: Many of Ringling's circuses are now attended by protesters, and the public backlash against animal performers—SeaWorld's stock dropped 50 percent after the 2013 documentary Blackfish lambasted its treatment of captive orcas—made the commitment of Ringling's elephants to circus life politically impossible. "These are complex, intelligent animals, and this is a lousy, lousy, dirty, cruel business, and people see that," PETA President Ingrid Newkirk told The New York Times in March.

The CEC's staffers explain away contentious policies as concern for the elephants' welfare: Calves are separated from their mothers to keep them from hurting one another; elephants are tethered at night to prevent fighting and food theft; bullhooks are used lightly, and the elephants aren't afraid of them. But even with those assurances, it's hard not to feel a knee-jerk distrust of the whole operation, to perceive every mundane elephant expression as a morose one and to interpret general afternoon lethargy as deep animalistic depression.

Still, the CEC is also inarguably doing good. Because the 1973 Endangered Species Act bars the import of Asian elephants—added to the endangered species list in 1975—staffers like Kiso are also directly involved with conservation efforts in Sri Lanka, where the elephant population can be ruinous to locals and crops. The CEC's elephants were also part of a recent study that assessed what elephants' low cancer rate (about 2 percent) might teach scientists about curing cancer in humans.

It's also hard to reconcile the center's affable and detail-oriented staff with well-documented instances of trainers treating elephants with the compassion more typically reserved for a malfunctioning printer. Payne says "corrective action" has been taken over videos showing overzealous bullhook use, and calls those instances the exception rather than the rule. "[Groups like PETA] want to make a publicity splash," he says. "They wouldn't know how to care for an 8,000-pound elephant on a bet."