Humans are in the midst of what might be the biggest and most transformative mass migration in our species' history: off the land and into cities. In the middle of 2009, the number of people living in urban areas surpassed those in rural areas; by 2050, two-thirds of humans will be city dwellers. This mass urbanization will inevitably transform everything, creating new and pressing issues in the realms of public health, food security, economic stability, infrastructure development—and environmental safety.

Later this month, climate negotiators from over 190 nations will convene in Paris for what is called the 21st Conference of the Parties, or COP21. But perhaps the United Nations should have named it the Conference of the City-States. That's because converging on Paris this year will be mayors from major cities on every inhabited continent. And any consensus these urban leaders come to might have a bigger global impact than the agreements reached by the representatives of countries.

"When it comes to climate, cities are where the action is," says Michael Bloomberg, the former New York mayor who was appointed the U.N.'s special envoy for cities and climate change in 2014. He is now at the center of efforts to propel cities into the center of the global climate negotiations. Bloomberg dubs the growing population of urban dwellers the "Metropolitan Generation," and the U.N. estimates that the cities they live in are responsible for three-quarters of all greenhouse gases. This makes them a critical factor in the effort to restrain emissions enough to prevent the potentially catastrophic effects of a temperature rise of more than 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit over the coming decades.

The impact of climate disruption is already being vividly experienced in many cities around the world. Every inch of sea level rise threatens more homes, highways and businesses, and extreme storms can devastate infrastructure and housing stock, as occurred with Hurricane Sandy when Bloomberg was mayor of New York. This past season, wildfires have taunted cities on the edge of grasslands and forests, demonstrating what past Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predictions mean in practice for the Western and Southwestern U.S.: that for every 1.8-degree Fahrenheit rise in temperature, the risk of wildfires increases, depending on location, as much as 100 to 300 percent. A recent economic study conducted under the watch of two former U.S. treasury secretaries—Republican Hank Paulson and Democrat Robert Rubin, working with Bloomberg—estimated that hundreds of millions of dollars will be added to city budgets from these and other climate-related disruptions if emissions continue on the same trajectory.

Municipal officials are normally overshadowed by more powerful heads of state, and in the past they have been largely left to improvise through the formidable challenges presented by climate-related disruptions. But mayors have far more room to act than national governments, which are often hamstrung by fossil fuel companies trying to influence climate policy. Local governments also have far more control than their national counterparts over a multitude of quotidian factors that are significant contributors to greenhouse gas emissions—from transporting people to and from work, to processing waste, to the efficiency of electricity use in office and residential buildings. City leaders have also begun to realize there is often more common ground between their different municipalities than there is between a given city and the rest of the country where it is located.

However, to date there's been little global coherence to urban climate strategies. "Thousands of cities are undertaking climate action plans," the IPCC wrote in 2014, "but there has been little systematic assessment of their implementation, the extent to which emission targets are achieved, or emissions reduced."

One of the biggest challenges cities face in getting together on a plan is a new twist to the ongoing tension between the have and have-nots that has resonated at every climate summit. In this instance, it's about how to deal with the large discrepancies between who creates greenhouse gases from industrial production and who consumes the goods that are produced. For cities in developed countries like the U.S. and those in Europe, reducing emissions is largely about the nitty-gritty of urban life—from encouraging mass transit, to more efficient waste-disposal systems, to increasing the emphasis on the "greening" of buildings. When Bloomberg was mayor of New York, his administration increased energy efficiency in office buildings and homes, planted almost a million trees to soak up carbon from the atmosphere, and bolstered public transit, setting the city on a path to reduce emissions by 20 percent by 2030.

However, although relatively wealthy cities like New York and San Francisco are taking important steps to make themselves more green, they are not yet taking into account the fact that they might be essentially outsourcing their industrial greenhouse gas pollution to poor urban centers. When, for example, American steel factories or British textile factories fled their countries in the 1980s and '90s, the greenhouse gases these industries produced went with them. Today, the new industrial cities of the world—Guangzhou in China (steel) or Tirupur in India (textiles), for example—are producing greenhouse gases on behalf of the postindustrial parts of the planet.

The same holds for many other heavy-polluting industries that fled overseas in the wake of global trade agreements. In the U.S. and Europe, 21 and 23 percent of greenhouse gases, respectively, are generated through industrial production; in China, the figure is about double that. And the World Bank estimates that at least a quarter of China's emissions are tied to exports to the U.S. and Europe.

"This is certainly a hot-button question," says Elizabeth Stanton, who produced greenhouse gas inventories for several U.S. cities while an analyst at the Stockholm Environment Institute and is now the principal economist at the Boston-based consulting firm Synergy Energy Economics. "There's a big correlation between those cities with a green consciousness and higher income."

Some of the greenest cities in America, measured by emissions per capita and other sustainability factors (New York, San Francisco, Seattle and Minneapolis, for example), are also in the highest ranks of per capita income. The same is true for European cities such as Germany's Hamburg, London and Paris. But, as Stanton points out, "in affluent areas what you find is that there's more spending and more income generated to purchase things not made there."

Many of those things—cars, appliances, the steel used to build skyscrapers—come with a heavy greenhouse gas load, raising a difficult question: Who is responsible for those emissions? Stanton and others have begun to make those calculations, which present a challenge to our definition of what it means to be "green." In the greenhouse gas accounting business, it's known as consumption-based accounting. And most U.S. and European cities have approached it with extreme wariness. "They're not going to run off to do consumption-based accounting, because they're not exactly anxious to go figure out how not green they are," Stanton says.

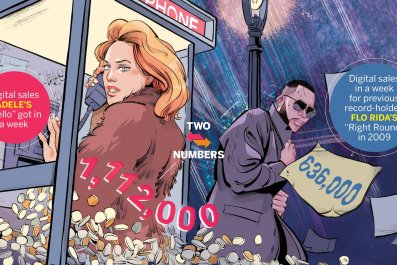

In the few cases in which cities have done the counting, the results have been revealing. In New York, a 2013 greenhouse gas inventory identified the stark difference between production- and consumption-based emissions. The former counts emissions from on-site sources like transport, manufacturing and electricity; the latter counts the quantity of greenhouse gases embedded in what residents consume. Most of the 90 ZIP code-based quadrants on the island of Manhattan, where there is little industry, feature per-household production emissions of between 1 and 5 tons per household. On the other hand, a consumption-based count shows an entirely different result, with most of the ZIP codes showing emissions of from 4 to 10 tons of carbon dioxide per household. In San Francisco, when consumption-based emissions are included, city residents' per capita emissions more than double.

Cities have limited leverage beyond their borders; while many are making real advances in reducing their carbon footprint, the next level of "greening" will require building a bridge across the large economic divide that separates producers from consumers. But that won't happen until those on the other end of that long supply chain begin to recognize the environmental impact of their consumption. "I haven't yet seen a campaign saying, 'Consume fewer televisions' or 'Don't lease a car every two years,'" says Brian Holland, climate programs director for the Local Governments for Sustainability, which devised the protocols that cities use to count their emissions.

On December 4, Bloomberg and Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo will co-host the first Climate Summit for Local Leaders, within the larger climate meeting. At least 300 mayors are expected to attend the all-day event at Paris's city hall, the Hôtel de Ville, with the goal of giving all cities a "united foreign policy," says Bloomberg . Their price of admission: to sign a compact committing them to conduct an inventory of city emissions according to uniform international standards and commit to a verifiable plan to reduce them. For the first time, we'll get a clear picture of where, exactly, urban emissions come from and thus how they can be specifically targeted, city by city. This will also offer insight into who may be responsible for them on the other end of the supply-demand chain; the compact spokesperson claims it will begin the process of counting consumption-based emissions next year.

"We can no longer postpone actions against the consequences of climate change, which we already are feeling," says Eduardo Paes, mayor of Rio de Janeiro, and chairman of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, a network of megacities that offers a forum for urban leaders to exchange information on how best to reduce their contributions to climate change and adapt to its already disruptive consequences. Rio, like other cities in the global south, has experienced a range of recent extreme weather events, including avalanches due to sudden violent rains and a continuing drought that is stressing water supplies across Brazil.

The mayoral compact signatories are hoping to formalize technology exchanges enabling member cities to learn from what Bloomberg calls "an ongoing laboratory" for experiments in limiting fossil fuels while sustaining complex and modern urban infrastructures. Los Angeles gets ideas about rapid transit bus lanes from Bogotá, Colombia; San Francisco offers advice on green buildings to cities in China; New York consults with coastal cities on reinforcing more resilient shorelines. And city planning agencies need to start catching up to the tumultuous physical changes already underway. As Mark Trexler, CEO of the Climatographers, a consulting firm specializing in climate risk, puts it, "the normal planning in five- or 10-year increments may become totally irrelevant when major areas of your coastline, for example, may be underwater."

Mark Schapiro is the author of Carbon Shock: A Tale of Risk and Calculus on the Front Lines of the Disrupted Global Economy.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Eduardo Paes is the chairman of the Compact of Mayors. In fact, he is the chairman of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group.