"Nobody walks in L.A."

—Missing Persons, "Walking in L.A.," 1982

There has never been a more quintessentially Los Angeles family than the Farriers, who in the 1960s made the freeways their home. They had owned a house in Tujunga, but it became too expensive to maintain, so they sold it. They were left with a camper and the asphalt ribbons that weave through the canyons and valleys of the unruly city. The freeway was both their means and their end.

In the morning, they drove from the downtown lot where they parked each night north on the Hollywood Freeway, to where Steve Farrier worked in Burbank. Then Marilee Farrier drove on the Golden State and San Bernardino freeways to El Monte, on the east side of Los Angeles County, where she deposited the couple's baby with her mother. She then got back onto the San Bernardino and drove to West Covina for her job at a department store. In the afternoon, she used the San Bernardino to return to El Monte for her baby. Following that, the Golden State and the San Bernardino whisked her back to Burbank. Reunited, the three Farriers cruised on the Hollywood Freeway back downtown.

They drove this 128-mile route each day, but being freeway nomads did not bother the Farriers all that much. "We've really begun to feel that the freeways, particularly the Hollywood Freeway, which is a beautiful road, belong to us," Steve told Cry California magazine, where the story of his remarkable family first appeared in the summer of 1966. His chief complaint about living in the camper was the frequency with which the toilet demanded emptying. "Frankly, we use the toilet as little as possible," he confessed.

The Farriers were, it turned out, an invention of Cry California. Like every successful hoax, this one was a close relative of reality. Said one observer, "I suspect that people like the Farriers are driving about Los Angeles today."

If the Farrier story appeared today, their living out of a car would not seem remarkable, at least not to anyone who has seen subdivisions across California emptied by foreclosure. More implausible, from a contemporary perspective, is how little time they spent sitting in traffic. This, more than anything else, would rouse suspicions in all those for whom the Sepulveda Pass at rush hour is more punishing than anything Dante imagined. Traffic doesn't get much worse, at least not in the developed world. A 2008 study by the Rand Corp. struck a lonely note of solace: Things are not as bad in Los Angeles as they are in Jakarta, Lagos or Bangkok. Yet.

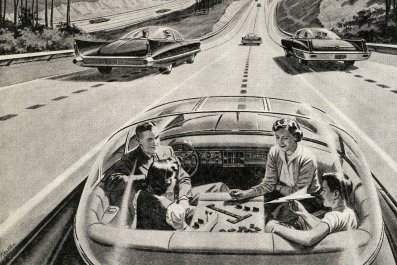

This is the city Eric Garcetti inherited, but it is not the city he wants to leave behind. Now in his third year as mayor, the 44-year-old Democrat wants Los Angeles to be "the first postmodern city," as he tells me, speaking in his art-filled office one morning in October. Throughout the past year, he has made a series of proposals that would fundamentally alter the city by deposing the automobile, which has reigned over Los Angeles for a half-century like a cocksure Third World despot. Garcetti thinks he can tame the four-wheeled beast through a series of measures that will get Angelenos walking, cycling and using public transportation. Call him the Che Guevara of Southern California infrastructure. If his revolt succeeds, it could spread across the nation: pedestrian plazas in Houston, bike lanes in Atlanta, a reclaimed riverfront in St. Louis.

Cities around the country are watching Garcetti, since traffic is getting worse everywhere. According to Inrix, a company devoted to the study of traffic, the worst commutes in the United States are in the Washington, D.C., area , where lobbyists and the politicians who love them spend 82 hours per year in logjams Congress would be proud of. The Los Angeles area is second, with 80 hours of freeway hell, but the metro regions of San Francisco (78 hours) and New York (74 hours) are close behind. Another study, by the American Highway Users Alliance, found that the severest bottleneck in the country was a stretch of Interstate 90 through Chicago. Many of the worst bottlenecks are in reliably constipated Los Angeles, but the top 10 is rounded out by charming little Austin, Texas, with San Francisco, Boston, Seattle and Miami also faring poorly.

There are more pressing problems in the world than your morning commute, but traffic woes can't be dismissed as #FirstWorldProblems. The $160 billion we lose in what Inrix calls "delay and fuel cost" related to traffic is more than the gross domestic product of Hungary. As for the 6.9 billion hours we collectively spend sending death stares into the immobile Prius in front of us, that is "more than the time it would take to drive to Pluto and back, if there was a road." It is fair to say that any infrastructure problem that requires an analogy to outer space to describe its full scope is not going to be an especially easy one to solve.

"We are prepared to endure considerable public outcry in order to pry John Q. Public out of his car."

—Caltrans official, quoted in Joan Didion's "Bureaucrats," 1976

The centerpiece of Garcetti's vision is Mobility Plan 2035, released last summer, its name a subtle allusion to the immobility that now grips every corner of this huge and restless city. The new mobility would come at the expense of the car. There is also Vision Zero, an initiative to eliminate traffic fatalities modeled on Stockholm's program of the same name. Los Angeles also has Great Streets and Complete Streets and People St, all different plans to fight the same four-wheeled enemy. There will be a subway to the sea, finally. There are now bus shelters with smartphone chargers. There are pedestrian plazas in downtown, which is now called DTLA and increasingly looks like the downtown of a real city. The Los Angeles River does not yet look like a river, but if Garcetti has his way it will, and people will jog and bike along its banks, just as they do along the Hudson.

As if all this were not enough, Garcetti has launched a campaign for Los Angeles to host the 2024 Summer Olympics. His infrastructure plan could benefit that bid, while the bid could generate funds for the infrastructure plan. Of course, both could come to naught, embarrassing Garcetti and convincing Angelenos that theirs is a fundamentally intractable city.

By 2024, Garcetti will no longer be the mayor of Los Angeles, though where exactly he will be by then is a matter of frequent speculation. Many think he yearns for a stint in Sacramento, as California's governor, or in Washington, as one of its two senators. Very few mayors of Los Angeles have ever achieved such prominent office, largely because it's hard enough to keep a city of 500 square miles and 4 million people from devolving into chaos. Trying to make that city friendly to bicyclists and pedestrians might be politically unwise, if not outright insane. But if Garcetti can do that, he can credibly promise to fight greater evils: overcrowded prisons, global warming, pension mandates, the Kardashians.

Not everyone, though, is sold on Garcetti's vision. His detractors live in wealthy enclaves like Beverly Hills, where the high hedge rules and pedestrians arouse alarm; others are in the immigrant communities of East Los Angeles, where people are worried about schools and jobs, not curbside plantings and dedicated bike lanes. "You cannot have a world-class city that's falling apart," says Laura Lake of Fix the City, a group that has been fighting Garcetti in court, so far without much success. "And we're falling apart." She points to potholes that proliferate on city roads like acne on a teenager's face. The buses do not run on time. Water mains break, turning streets into lagoons. The homeless wander the very streets Garcetti likes to celebrate as havens of the New Urbanism.

To more philosophical detractors, Garcetti's distaste for freeways is an abomination, a fundamental misunderstanding of the soul of Los Angeles. The car is the celebration of American individualism, and the freeway— free way—is where that national spirit roams. Our classics are On the Road and Easy Rider, not On the Light Rail and Contented Commuter . Columnist Joe Mathews recently argued in the San Francisco Chronicle that Los Angeles had "downsized its dreams" by deciding to build subway lines and bike lanes, which would only fragment a city the freeways had unified. Mathews doesn't quite call Garcetti an elitist interloper who doesn't understand the city he has been elected to govern. But he comes pretty close.

"Both sides," says Kevin Roderick of the news site LA Observed, "see this as a fight over the soul of the future of Los Angeles."

"Who needs a car in L.A.? We have the best public transportation system in the world."

—Who Framed Roger Rabbit, 1988

It is fitting that the shortest railway in the world is in Los Angeles and that it no longer functions, a handsome but useless monument to a bygone city. Opened in 1901, the Angels Flight funicular was really more of an elevator on an incline than a proper railroad. Nevertheless, it signaled the big-city aspirations of Los Angeles, whose population had just broken 100,000. Angels Flight connected the genteel residential neighborhood of Bunker Hill to the commercial district of downtown. In the 1960s, urban redevelopment leveled Bunker Hill, and in 1969 Angels Flight was dismantled and put into storage. It reopened in 1996, closed in 2001 after a fatal accident, came back to life in 2010, suffered another accident in 2013 and stopped running again. Today, Angels Flight is fixed on that incline, ready to go but going nowhere.

Angels Flight is a reminder that there was a city here before the freeways. Angelenos of a certain caste like to remind outsiders that the Red Car trolley system once featured 25 percent more track mileage than today's New York City subway. But the Red Car ceased to run in 1961, after years of declining service. There is, today, a Metro system of buses, light rail and subway, but it is a system of last resort. Ridership has declined now that immigrants without documentation are allowed to apply for a California driver's license.

The most ambitious of Garcetti's plans is a significant expansion of the Metro rail network. The push to expand subway service started under his predecessor, Antonio Villaraigosa, who in 2008 managed to pass a half-cent sales tax that will raise $35 billion for public transportation. Garcetti has doubled down: 11 subway, rail or bus projects are in either the planning or building stages. The most ambitious of these are the extension of the Expo Line light rail, which would finally connect downtown to Santa Monica and the Pacific Ocean, and the westward extension of the Purple Line subway along Wilshire Boulevard, considered by some to be the city's Main Street. But there will also be forays into the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, to the northeast, and a rail connection to Los Angeles International Airport.

The knock on Los Angeles has always been that it's a sprawling mess, but that's far closer to myth than to reality: Los Angeles is the second densest metropolitan region in the United States, after New York City and its direct environs. New York, though, works along a traditional urban model: Commuters take trains and subways into the incredibly packed nucleus that is Manhattan from the less crowded outer boroughs and suburbs. Los Angeles, conversely, is "both dense and polycentric," in the words of the 2008 Rand study on Los Angeles traffic. That's a challenge, it explains, because "the fact that population and jobs are spread out across more centers increases the difficulty of attracting sufficient ridership on any given link."

It is an article of faith among today's young urbanists that public transit will save the day, that cities with subways are superior to cities without them. But Frances Anderton, who hosts a design and architecture show on the public radio station KCRW , offers a note of caution. She went to school in London before moving to Los Angeles and still remembers that city's Tube system with a measure of dread. " Much as I am excited about the expansion of public transit, I am not romantic about its ceaseless joys," she says with customary British dryness. Anderton commutes to work on a bicycle and supports Garcetti's plans, but she believes that even if Metro service were dramatically expanded and improved, "there would still be enormous congestion." Too many people simply have too far to travel each day to too many different places, which is why drivers alone in their cars account for about 70 percent of the commuters in Los Angeles.

Joel Kotkin, the rare urbanist who does not think suburbia is hell with a backyard, recently wrote that the Greater Los Angeles area "should not prioritize our transit dollars" in trying to imitate New York or San Francisco, as any such effort was bound to fail. Both of those cities have central districts where commerce has been happening for centuries. Not so for bigger, younger Los Angeles. Only 3 percent of the area's workers, he pointed out, work downtown, which makes it not much of a downtown at all. Commercial activity is spread over a vast area that no transit system could possibly service. That view is supported, in part, by Paul Sorensen, one of the authors of the Rand study, who says new transit lines could never adequately compensate for the region's complex tangle of travel patterns.

Previous attempts to coax Angelenos out of their cars have generally failed. Today, though, demography is on the side of the New Urbanists. A Bloomberg projection has Los Angeles becoming the densest city in the United States by 2025. The freeways, which are choking today, will buckle under the weight of all those added millions. Expanding them will not help. A variety of agencies just spent $1.1 billion to add an extra lane to the northbound Interstate 405 through the Sepulveda Pass, one of the most congested stretches of freeway in the United States. The road closures that this five-year project involved were given apocalyptic names: Carmageddon, Jamzilla, the Rampture. About the kindest thing I could find about the improvement was from local public radio affiliate KPCC, which reported that traffic has gotten only "a little slower."

Brian Taylor, an urbanist at the University of California, Los Angeles, has offered an ingenious argument: Traffic is a sign of urban health, one we should embrace as we do a newborn's regular excretions. Cities like New York and Los Angeles are inundated with cars because everyone in the tri-state area wants to try a Cronut, because no Orange County weekend is fully lived without a trip to the consumer nirvana of the Beverly Center. "Cities exist because they promote social interactions and economic transactions," Taylor wrote in a recent paper. "Traffic congestion occurs where lots of people pursue these ends simultaneously in limited spaces. Culturally and economically vibrant cities have the worst congestion problems, while declining and depressed cities don't have much traffic." Just take Peoria, Illinois. (His example, not mine.)

Or not. A recent survey of Angelenos found that traffic is by far their biggest concern , with public safety a distant second (55 percent to 35 percent). So either these poor folks don't know how good they have it or Taylor's argument is better suited to the groves of academe than to the right lane of the 405.

There is always monorail. No, seriously. In 1963, the Alweg Monorail Company offered to finance the construction of a monorail system throughout the Greater Los Angeles area. The monorail would have cost $105 million, but the residents of Los Angeles refused. Some point to that as a watershed disaster , like the Red Sox trading Babe Ruth to the Yankees for $100,000. But Boston has transcended its curse. Los Angeles is still waiting.

"People have been walking in L.A. since before Columbus discovered America."

—Joe Linton, Streetsblog L.A. editor, 2015

The famous sunlight of Los Angeles is a crucial ally of Garcetti's. It is not like the sunlight anywhere else. It is not the cruel, scorching sun of Sacramento, nor the precious sun that sometimes punctures the coastal fog above San Francisco. It is so much more glorious than the sunlight of Chicago and New York that, when you first feel it on your face, you wonder if you have ever felt true sunlight before. What a shame, then, that so many Angelenos experience the beneficent Southern California climate only in driveways and parking lots.

If Angelenos did decide to walk more, they'd quickly find a city not especially suited to the enterprise, with wide boulevards that seem as perilous to cross on foot as freeways, and freeways over which "pedways" stretch like bridges to nowhere. The palm trees that Los Angeles is famous for provide scant shade along its thoroughfares and do not trap carbon emissions well, leading the City Council in 2006—then led by Garcetti—to put a moratorium on palm planting. About 40 percent of the city's sidewalks are cracked and, what's more, can be expensive to traverse: The Los Angeles Police Department aggressively enforces a state injunction against late crossings by ticketing people who start crossing at an intersection after the walk signal has begun to flash, sometimes levying fines of up to $200. It can seem like every force in Los Angeles is aligned against the pedestrian—other than that splendid and generous sun.

The company Walk Score gives Los Angeles a 64 out of 100 on its walkability index, two points behind Baltimore. Carey Waggoner, a fourth-generation Angeleno who grew up in Beverly Hills, says the only time she remembers walking in her neighborhood was in the wake of the 1994 Northridge earthquake, which isn't exactly what proponents of pedestrianism have in mind. New arrivals quickly adapt. Barry Harbaugh is a book editor who recently moved from New York City. "Way less destination walking going on during the week here," he reports, remembering the days when he would stroll through Central Park on the way to a work meeting.

Waggoner, who lives in New York, says she will "without a doubt" return to Los Angeles, evincing a civic pride many of the city's current residents do not feel. A recent Los Angeles Times article on low voter turnout speculated that Angelenos feel a sense of "detachment" and "community isolation." That reinforces the old quip (attributed variously to Aldous Huxley, Dorothy Parker and H.L. Mencken) that Los Angeles is "72 suburbs in search of a city." The famous insult is 16 short of the current number of municipalities in Los Angeles County, but it gets at the heart of the matter: It is hard to have civic pride if your knowledge of a city consists merely of traveling back and forth on its freeways. The dream of mobility has atomized the city, so that Angelenos know neither their city nor themselves.

Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne calls what's happening today the Third Los Angeles, following the oil boomtown of the 19th century and the suburban idyll of the 20th. As he told LA Observed , "Having run out of room to sprawl, virgin land to conquer, the city is doubling back on itself, constructing more infill development and experimenting with denser housing and vertical architecture. We are finally building a comprehensive and public mass-transit system to match the privately run one of the First L.A."

This Third Los Angeles is probably most evident downtown, on Broadway, where I met David Ulin, a native New Yorker who until recently was the chief book critic of the Los Angeles Times. Last year, Ulin published Sidewalking, a paean to walking in Los Angeles, which he has been doing for two decades, determined to prove to himself and others that they live in a real city. Downtown, he says, was "the most terrifying landscape I have seen" when he arrived there in 1991. Today, the only terrifying thing is the real estate prices, both commercial and residential, which have risen and will keep rising. Half the people there look like recent transplants from Brooklyn or Austin. Accordingly, hip hotels like the Ace and the Standard have followed, occupying historic buildings along the thoroughfare. The Grand Central Market is packed, as are celebrated new restaurants like Church & State and Bäco Mercat.

City planners love buzzwords that make the business of pouring concrete and chipping asphalt a sexy enterprise, but one that is genuinely germane to Garcetti's outlook is " Latino Urbanism," a term that describes the fluid interplay between the private and the public in places like Mexico City, a kind of thriving chaos. The concept is appropriate in a city that is about half Hispanic. Some, though, note the irony of Latino Urbanism pushing out long-standing businesses that catered to Spanish-speaking immigrants, replacing them with bars and boutiques for gringos in oh-so-ironic "Defend Los Angeles" T-shirts.

Garcetti tells me he is practicing "urban acupuncture," applying his vision of the city where it is most needed. When he was a city councilman in the youthful Silver Lake district, he successfully advocated for the conversion of a short stretch of road into a pedestrian plaza. It was the first such project in Los Angeles, which is accustomed to giving drivers more pavement, not taking pavement away from them. The Los Angeles Times deemed the 11,000-square-foot plaza "unusual," as if it were the obsidian slab that greets puzzled primates at the opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Garcetti remembers the outcry over the plaza, principally from local business owners. "For a few people there, you would've thought we were telling them they had to ride to work on a horse," he says. As a councilman, he also supported the creation of a " Hollywood Central Park ," parkland covering a below-street-grade section of the 101 freeway that is currently a gash through the city.

As mayor, Garcetti has added three pedestrian plazas in areas that aren't on the hipster radar: in middle-class, gentrifying North Hollywood; the vastly Hispanic neighbor of Pacoima in the San Fernando Valley; and traditionally black Leimert Park. His Great Streets initiative has tried to make wide, shadeless thoroughfares like Van Nuys Boulevard places where you might walk or even stop and sit to appreciate your surroundings. As he carves bike lanes out of surface streets and builds new subway lines, Garcetti acknowledges that this is a "painful moment" for Angelenos, particularly those who "worship" the car and have seen their deity maligned. "Most of us are polytheistic," Garcetti says, convinced that his city's fealty to the freeway is not nearly as strong as some think. That's a stark contrast to former Mayor Tom Bradley's assertion that people came to Los Angeles "looking for a place where they can be free." The means of that freedom was the freeway, a notion that today seems both ridiculous and naive.

Instead of trying to hang on to this outdated version of Los Angeles, Garcetti tells me he is doing "advance work for urbanists everywhere." The power structure of Los Angeles doesn't make that work easy. For one, the city's "weak mayor" system means he is routinely curbed by the City Council, though it has been generally receptive to Mobility Plan 2035 and other initiatives. More vexing is the fact that Los Angeles and Los Angeles County are hardly one and the same. Whereas New York's Mayor Michael Bloomberg could exercise his New Urbanist vision over all of the city's five boroughs, Garcetti is only the mayor of the city of Los Angeles, which is but one of those 88 municipalities in the county that most of us call "El Ay." He controls only 500 square miles in a city-as-county nine times that size. His fortunes at least partly depend on Santa Monica, which may want bike share, and Pomona, which may want extra lanes of freeway.

And not-in-my-backyard sentiment can be especially strong in Los Angeles, since many people have very nice backyards. Some at Beverly Hills High School, for example, tried to stop the Metro from excavating a subway tunnel underneath the school, claiming the school could fall victim to a methane gas explosion or even a terror attack. In Westwood, near the UCLA campus, some residents fought against bike lanes. Garcetti won both of those fights, but each skirmish takes time and money. It can sometime seem like the city's Westside—wealthier, whiter, more tied to the film industry—is opposed to Garcetti's infrastructure plans, while the Eastside—denser, hipper, full of immigrants—is for them. But that isn't exactly the case. Gil Cedillo, a city councilman who voted against Mobility 2035 and represents many poor and working-class Angelenos, has branded Garcetti's vision for Los Angeles "elitist."

"The road to hell is paved with good intentions—and with bicycle lanes on each side of the pavement."

—John Marshall, letter to the Los Angeles Times, 2015

Cycling may be abhorrent to some in Los Angeles, but it certainly isn't new. In 1900, the developer Horace Dobbins opened the Cycleway , a bicycle path between Pasadena and Los Angeles, made of pine slats and elevated as high as 50 feet above the ground. Only a little more than 1 mile of the 9-mile Cycleway was ever completed, and the rise of the car relegated the quirky project to oblivion. But it is a reminder of what may have been, and what could be again.

Garcetti's predecessor, Villaraigosa, was a champion of bicycling. In 2010, he was riding his bike after a workout down Venice Boulevard in the busy Mid-City neighborhood when a cabbie cut him off. The mayor stopped short and went flying over his handlebars, breaking his elbow. Angelenos took notice. If the city's chief executive wasn't safe on a bike, then who was?

The cabbie surely made an innocent error, though in Los Angeles one can't be sure. Even given the widespread antipathy to bicyclists, the antipathy to bicyclists in Los Angeles is especially strong. Last year, lifelong Angeleno Jackie Burke told NPR how she felt about the rising popularity of bikes: "It's very frustrating, to the point where I want to just run them off the road. And I've actually kind of done one of those drive-really-close-to-them kind of things just to scare them, to try to intimidate them to kind of get out of my way."

Some wonder if it's worth it, given that only 1 percent of Angelenos bike to work. Even with the addition of hundreds of miles of bike lanes under Mobility Plan 2035, how much can that share of commuters ever increase? Bruce Feldman, a longtime resident of Santa Monica, recently reminded Garcetti that Los Angeles "is not Stockholm" and took issue with the mayor's "road diets": the bike lanes, pedestrian-friendly planters and other alterations that all take space away from cars on surface streets. "Your road diet would make congestion in our expansive region much worse than it already is," Feldman argued. "If you squeeze an ever-increasing number of cars into fewer lanes, what other outcome can you expect?"

Nobody is a bigger booster of biking in Los Angeles than Joe Linton, who runs Streetsblog Los Angeles , a website devoted to promoting bicycling and walking. He is at once hopeful and frustrated, encouraged by Garcetti's vision but worried that "L.A. hasn't been nimble enough." Linton says the city has been installing bike lanes (46 miles under Garcetti) in neighborhoods where it knows there will be little resistance, on streets where major sacrifices (i.e., car lanes) won't be required—in essence, padding the numbers without improving the cycling experience. In New York, conversely, Mayor Bloomberg forced residents to get acclimated to dedicated bike lanes by putting them on some of Manhattan's busiest thoroughfares, including Broadway. But any comparison to New York clearly bothers Linton. "It's not gonna look like New York tomorrow," he says. "It's not gonna look like New York in 20 years."

On the other hand, Los Angeles has many broad and underused streets, as well as wide sidewalks that get little foot traffic. Dedicated bike lanes would be easier to build here than in dense Manhattan, where every inch of pavement is a precious resource fought over by drivers, pedestrians and cyclists. "I'm convinced L.A. has the potential to be the best city to ride a bike in America," wrote journalist Peter Flax . Many more bike lanes are planned, and downtown Los Angeles should have a bike share in place in the first half of 2016. In 2010, Los Angeles didn't even make the list of Bicycling magazine's top 50 bike-friendly cities in the United States. Four years later, Los Angeles was 28th, leaving Omaha (47th) in the dust.

"This is certainly a noble stream to be found running in a semi-arid country."

—William Mulholland, chief engineer of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, 1904

One of the more telling views of the city is from the Avenue 26 Bridge, near the intersection of the 110 and 5 freeways. On Google Maps, the many ramps look like a nest of pale-yellow snakes. The view in real life reveals no hidden beauties. Standing on the bridge, you are offered none of the classic Los Angeles scenes: no Hollywood sign, no Sunset Boulevard. Pacific Palisades might as well be in another country.

Instead, what you see is traffic on the 110 creeping glacially, a multicolored ice floe from which the occasional shard disassociates, floating toward an exit ramp. Next to the freeway, sharply sloping walls of concrete cradle where they meet a flimsy stream of water. This is the Arroyo Seco, one of the tributaries of the Los Angeles River, which is trapped in concrete for about 43 of its 51 miles as it passes through the county. The river is so unglamorous and neglected, there must be many who drive along its banks each day but do not know that it exists.

The Los Angeles River may be an urban tragedy, but the final act remains unwritten. If its entire length were opened up to foot and bike traffic, as some desperately want, the river would connect disparate communities in Los Angeles like no other project since the freeway. Open a river and close a wound, one that is as much psychic as it is physical.

For this was once a beautiful place. In 1769, Spanish settlers arrived in what is today known as the Arroyo Seco Confluence, where the Arroyo Seco flows into the Los Angeles River. In his writing, Father Juan Crespí described embankments "very well lined with large trees, sycamores, willows, cottonwoods, and very large live oaks." But the river also had a tendency to flood. After a particularly brutal deluge in 1938, the Army Corps of Engineers was called in to build what is essentially a protective sleeve of concrete around the river. It may be ugly, but it works—the river does not flood anymore.

A few stretches of the old beauty do remain, enticing reminders of what the river once was. One of these is the Glendale Narrows, where the concrete slopes lead to a riverbank that is as organic as hipster coffee. Willows hang over water that rushes over rocks. For a moment, as you move through the thicket of trees toward the river, through the dappled light, your hear only the rush of water. You can forget that you're in Los Angeles; you can forget that you're in the 21st century.

Recently, the Los Angeles River has come to figure into Garcetti's infrastructure plans. In fact, it may be the most potent symbol for those plans, even though its waters will never bear commuter ferries or tugboats. To restore the river would be to restore some earlier version of Los Angeles, one more attuned to the land on which the city sits and the people who live in that city.

There have been plans to fix the river before, but Garcetti has secured a promise of $1.3 billion from the Army Corps of Engineers to undo its 80-year-old "improvement" by partly removing the concrete straitjacket that has strangled much of the river. The plan still needs congressional approval, but designs suggest that the Los Angeles River may, one day, look like a natural waterway, at least in places. But as with pretty much all of Garcetti's infrastructure plans, things quickly became much more complex. Shortly after the Army Corps funding seemed to move forward, the Los Angeles Times revealed that the mayor had quietly enlisted Frank Gehry to draw up a plan for the entire 51-mile river.

The backlash to the Gehry announcement was swift and surprising. "Last time there was a single idea for the L.A. River, it involved 3 million barrels of concrete. To us, it's the epitome of wrong-ended planning. It's not coming from the bottom up. It's coming from the top down," said Lewis MacAdams, who founded Friends of the Los Angeles River three decades ago and has done more than anyone to attenuate the frequency with which the river is likened to a gutter. He also suggested that Gehry's participation would imperil the federal funding by declaring the Army Corps persona non grata, now that a starchitect was involved. Alissa Walker, a Los Angeles–based urbanist blogger, argued in Gizmodo that Gehry's work "rarely provides true public space and doesn't show many gestures to the natural environment." An architecture critic for the Guardian warned that Gehry needed to "suppress his expensively eye-catching clich é s and channel the spirit of his early work."

Others worried that the Los Angeles River was being remade not as a public good but as a private asset to be enjoyed only by the wealthy whites who would inevitably move to condominiums along its banks. You could feel, in the Los Angeles press, crosscurrents of anxiety and hope, blowing as ferociously as the Santa Ana winds. Early in his mayoralty, Garcetti was criticized by some for an aversion to risk. Now he was promising to give Los Angeles a river where, for decades, there has only been a rivulet. To clean up a river is a matter of custodianship; to make a river flow out of concrete might be closer to magic.

"A city built for driving better be good for driving."

-Tim Sullivan, Ways to the West, 2015

The most convincing argument for how to save Los Angeles comes from the 2008 Rand study. More than 500 pages in length, it has sections with click-bait titles like "Inadequate Explanations for the Severity of Congestion in Los Angeles" and "Congestion Is a Nonlinear Phenomenon." The authors of the report are dedicated urbanists who would recommend unicycles if they thought that would save the city.

Though the study predates Garcetti, it convincingly argues that bike lanes and sidewalks aren't the powerful decongestants the city needs. The authors are pessimistic about public transportation too. The Rand folks say only one thing can stop traffic: lowering demand for driving. And it's pretty basic economics that raising the price of something decreases demand for that service or product. That's exactly what the Rand study recommends, urging Los Angeles to charge drivers for using certain routes during rush hour and parking in desirable areas during business hours. Sorensen, one of the authors, says tolls from congestion pricing could go to improving public transit, thus offering more options for those who can't pay the new driving "tax."

London is the biggest city in the world to try congestion pricing, instituting the practice in 2003. It did seem to lessen traffic for a few years, but gains stagnated in 2007 , and London remains one of the most congested cities in Europe. Mayor Bloomberg sought to institute congestion pricing in Manhattan, but he was foiled by the outer boroughs, many of whose working-class residents rely on cars. As the Rand study acknowledges, making people pay to drive may just mean that the poor will drive less.

"No plan to institute congestion pricing within city limits," Los Angeles Department of Transportation spokesman Bruce Gillman tells me, though he points out that Los Angeles has a "congestion parking" system downtown. Caltrans, the state authority that controls the city's freeways, has dynamic tolling on the Harbor Freeway, but the Los Angeles Times reported that "so many drivers now steer into the Harbor Freeway's northbound toll lanes to escape morning traffic jams that the paid route is slowing down too." As for strict congestion pricing on county freeways, Caltrans spokesman Micole Alfaro says his agency "has no plans."

"You can't do congestion pricing across the entire Southland," says Anderton, the KCRW host, using the place-name for the Greater Los Angeles region. " I'd imagine congestion pricing can only work when drivers have alternative modes of transit. Most here don't."

"I cannot find it in me to complain about the freeways of Los Angeles; they work uncommonly well."

—Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies , 1971

Things on the freeways are only getting worse. A report by the federal Department of Transportation has predicted that soon "transit systems will be so backed up" around the nation "that riders will wonder not just when they will get to work, but if they will get there at all." If that comes to pass, Los Angeles may long for the days when it was being favorably compared to Jakarta.

The traffic in Los Angeles has become so bad, it's like the Eiffel Tower that writer Guy de Maupassant deemed "an unavoidable and horrible nightmare," one that eventually drove him out of Paris. But while the tower looms vertically, the freeway pervades L.A. horizontally, an anxiety that snakes through every part of the city. "People think about it all the time," Sidewalking author Ulin says.

Last April, a mountain lion became the newest celebrity in Los Angeles. He did so by crossing the 101 freeway in search of a new home, having been pushed out of his birthplace in the Santa Monica Mountains. The National Park Service named him P-32, and as he crossed highways, pushing north and east, he became a folk hero, a symbol of nature's trace in a city that is often regarded as unreal and hostile to all living things, including humans.

P-32 crossed the 23, the 118, the 126. But then he got to the 5, near Castaic Lake. It was August 10, early in the morning. Trying to get across the highway, P-32 was hit and killed. He was 21 months old. Hundreds of people die on the freeways of Los Angeles each year, but the death of a mountain lion touched a new and painful nerve. And though no one will stop driving because of P-32's demise, the accident did remind people that driving has costs that we should not have to pay. There have been renewed efforts to build a wildlife overpass for the 101, which would have made a crossing like P-32's less perilous. Animals, it turns out, have as hard a time getting around Los Angeles as humans do.