Every March, aspiring doctors around the country open their match envelopes to discover where they'll spend the next few years of their lives. Soon afterward, they officially earn their MDs as they graduate from medical school and head off to continue their training as interns and residents.

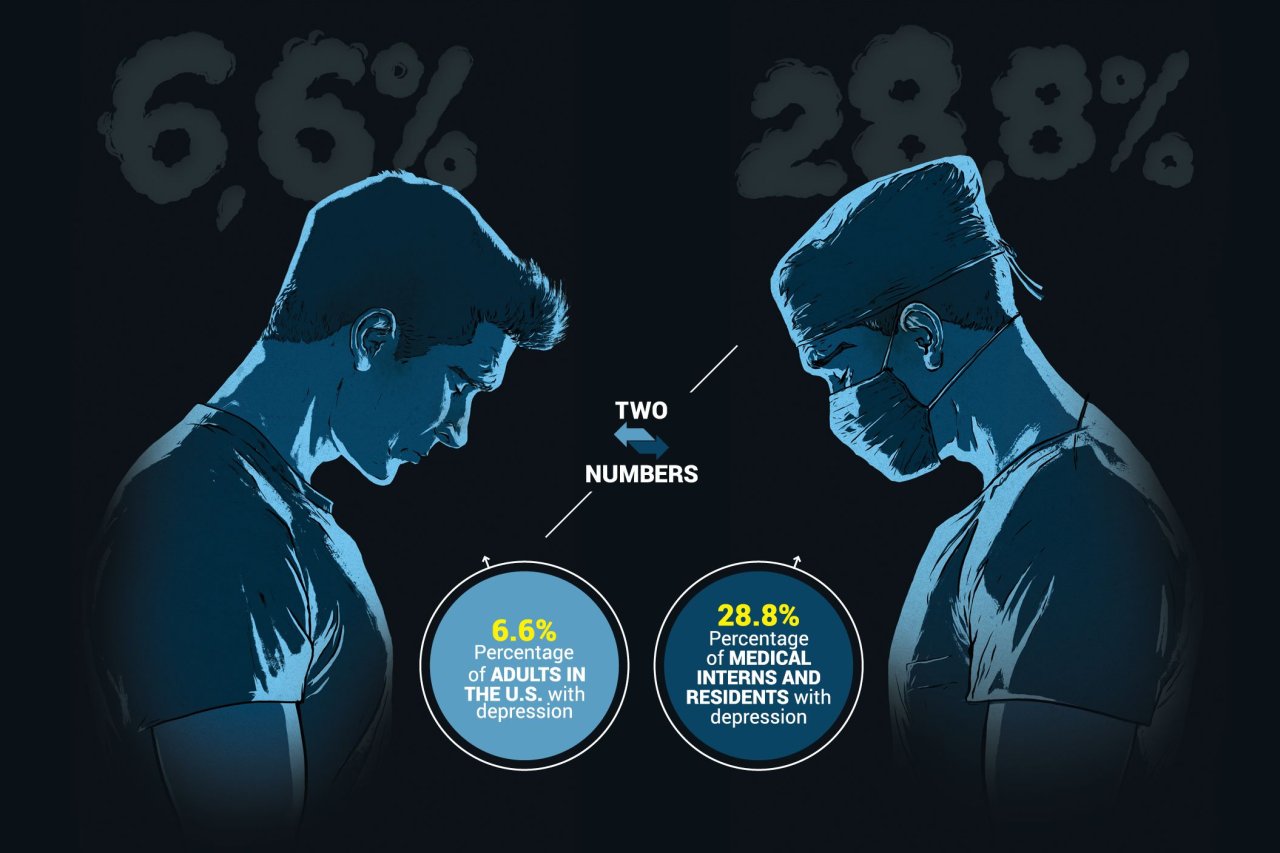

During this grueling next phase of the process, more than a quarter of them may become depressed or show depressive symptoms, according to a paper published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association. In "Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms Among Resident Physicians," researchers looked at dozens of relevant studies published between January 1963 and September 2015 to try to pin down the rate of depression among residents and interns (a title used for new doctors during their first year of residency).

"The rate of depression in this population of training physicians is remarkably high and higher than the general population," says senior author Dr. Srijan Sen, an associate professor in the University of Michigan's psychiatry department. Depression can obviously have a negative impact on the doctors-in-training themselves, says Sen, but it can also affect the patients in their care, since mental health issues are linked to medical errors. Medical errors, in turn, can make residents more likely to become depressed.

Sen is also the principal investigator on the Intern Health Study, which tracks stress and depression in new doctors over time, beginning prior to the intern year. While conducting that primary research, he and his colleagues came across several studies that examined depression during internship and residency reporting vastly different depression rates.

He worked with first author Dr. Douglas Mata, a resident at Brigham and Women's Hospital and clinical fellow at Harvard Medical School, and other colleagues to analyze and combine data from 31 cross-sectional and 23 longitudinal peer-reviewed studies.

They found that the overall rate of depression and depressive symptoms among interns and residents was 28.8 percent, with a small but significant yearly increase over the five decades they examined (roughly 0.5 percent increase per year). Of the 54 studies included in the meta-analysis, only three used clinical interviews to assess depression, while the rest relied on various methods of self-reporting. When the researchers grouped studies by the type of screening and the threshold used to deem participants depressed or not, the prevalence ranged from 20.9 to 43.2 percent.

In contrast, roughly 6.7 percent of adults in the U.S. experience a major depressive episode in a given year, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, while Sen says the lifetime prevalence for depression is about 20 percent in women and 12 to 14 percent in men.

"Nailing down a number and where exactly the depression rate is [during residency] is useful," says Sen, who was inspired to start the Intern Health Study after his own internship experience. He describes the stark contrast between meeting a well-adjusted group before the year began to watching colleagues struggle with depression a few months later.

The meta-analysis published Tuesday "raises a lot of questions," he says, and it demonstrates that depression during residency is "really a problem and one of big proportions."

In a secondary analysis of seven longitudinal studies, the researchers also found that the risk of depression increased 15.8 percent when recent MDs entered residency.

Sen's Intern Health Study, which has reached a sample size of more than 10,000, has shown a similar striking change; the depression rate increased from roughly 3 percent before the beginning of internship to 26 percent during the first year. The rates later went down to 10 to 15 percent and have stayed there as far out as the study has tracked to date.

In other words, Sen says, there's something specific about the intern experience that's increasing depression rates. He points to long hours as one of several factors. Despite national regulations that in 2003 set a weekly limit of 80 hours and in 2011 reduced the number of hours interns can work in a row (from 30 to 16), a 2013 paper out of the Intern Health Study published in JAMA showed that while average duty hours decreased slightly, sleep and depression rates did not improve, and medical errors increased. It's possible that's because the workload has not decreased with hours, he says.

But hours are not the only problem, says Dr. Thomas Schwenk, a professor of family medicine and the dean at the University of Nevada School of Medicine, Reno, whose editorial "Resident Depression: The Tip of a Graduate Medical Education Iceberg," was also published Tuesday in conjunction with the Mata and Sen's study.

The work-hour rules essentially decrease exposure to a toxic environment, Schwenk tells Newsweek, without necessarily addressing the underlying qualitative issues. During residency, new doctors face huge stresses, burdens and demands, he says, and deal with ethical dilemmas, technological decisions and patient expectations.

"There's a tremendous amount here that we're not helping them internalize," Schwenk says. "These are very traumatic experiences that they have, and we're not really there for them as used to be the case." Schwenk cites fast pace and requirements of today's clinical system as factors that prevent interns and residents from getting the kind of mentorship and support he feels his own generation received.

At the same time, Schwenk and Sen agree, many doctors do not get help when they suffer from depressive symptoms because of time constraints, stigma and fear of consequences to their professional futures.

"The solutions to this endemic can be classified into three categories," wrote Schwenk in his editorial, "provide more and better mental health care to depressed physicians and those in training, limit the trainees' exposure to the training environment and system that are thought to contribute at least in part to poorer mental health and wellness, and consider the possibility that the medical training system needs more fundamental change."

Residency training programs as they're currently structured, Schenk says, are grafted onto clinical systems that happen to teach new doctors. Perhaps what's needed is the reverse, he suggests: a program in which doctors-in-training happen to see patients "even at loss at clinical productivity and revenue."

"There has been little willingness or energy to change the system," Schwenk wrote, but "the study by Mata et al. suggests there may be no choice."