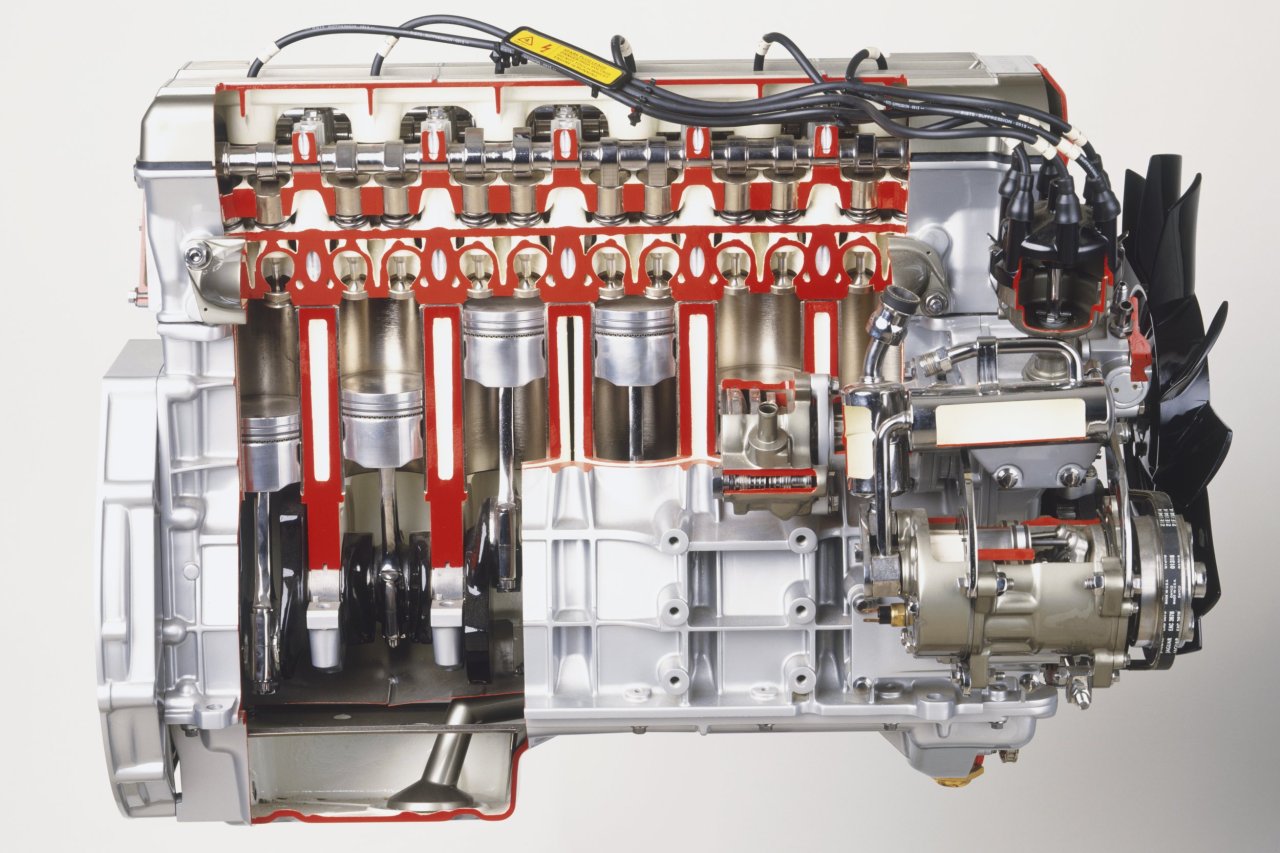

The massive 6.2-liter V-8 engine in the white 2010 GMC Yukon Denali does exactly what you'd expect when you step on the gas: It moves, lumbering up the steep, seaside road on the Pacific side of San Francisco. It does the same when you turn around and go down the hill, or when you level out the speed and cruise by miles of beach at 50 miles per hour. All this would be unremarkable if it weren't for the complicated dance under the hood, where software is selectively firing each of those eight cylinders.

Fuel efficiency isn't the most exciting thing about driving a car, but in this case, that's the point. A Silicon Valley company named Tula modified the truck so that its engine can now choose which of its cylinders fire and when, conserving energy with no noticeable loss of power—a technology the company calls "dynamic skip-fire."

The Denali uses every bit of its 403-horsepower engine to get up to 60 mph, but once it's there, the vehicle needs a lot less to keep moving—something closer to 30 horsepower. Imagine making an omelet, says James Zizelman, a managing director at Delphi, a company that recently acquired a stake in Tula and helped outfit the Denali. You probably don't need more than three eggs, right? But, says Zizelman, "in most cars, you're pouring out parts of eight different eggs to make a three-egg omelet." In other words, there's a lot going to waste. "This technology lets the car use just what it needs," he says.

Systems that deactivate cylinders to conserve energy while a car is on the move aren't new; they were first tried by Cadillac after the oil shocks of the late 1970s. But engines like that on the market now act in only a few configurations, usually switching some cylinders off when the car needs less power. Tula's dynamic skip-fire, on the other hand, constantly changes which cylinders are firing. In the test truck, a panel of flashing green lights shows the software picking what to fire when, turning all green when I push down the gas and turning into a blur of white flashes showing dormant cylinders when I coast.

The result, Tula says, is a 15 to 20 percent fuel gain without any major changes to the engine. While that doesn't sound like much, it has huge implications for an industry facing daunting new regulations. In August 2012, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Transportation mandated that the average consumer vehicle get 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025, roughly matching Europe and China's guidelines. Right now, most new cars and trucks in the U.S. average just 24.3 miles per gallon according to the EPA, leaving manufacturers just nine years to nearly double what your car can get on a tank of gas. While electric cars can help that average, the combustion engine isn't going away any time in the next decade, and even hybrid cars use combustion engines to charge the electric motor and take over when the battery power dwindles.

Car companies will probably get to 54.5 by making a lot of tweaks to their fleets, like adding more turbochargers (which increase efficiency by forcing extra air into the engine) and designing engines that stop at red lights. A software solution, like Tula's, would be enormously attractive because it's relatively cheap—estimated to be just $350 for the improvement to that white Yukon Denali. It also means car companies could continue to use their current engine designs on future car models.

Tula is testing its technology on a smaller car, a Volkswagen Jetta, to see what improvements it'll make there. Delphi and Tula say they are in discussions with several major auto companies in the hopes that dynamic skip-fire will be in a production car by 2020.