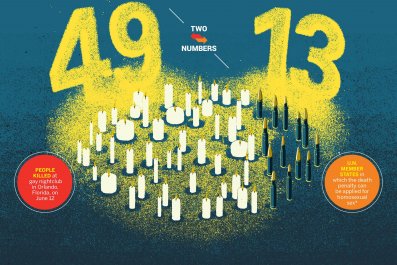

The cellphones of dead people were still ringing inside the Pulse nightclub on June 12 when Cathy Lanier, chief of the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C., got a message from her counterparts in Orlando, Florida. First reports were that a terrorist had carried out "the worst mass murder in American history" there.

A famously hands-on and nocturnal leader, Lanier started punching numbers on her cellphone. One call went to the Joint Terrorism Task Force, the FBI-led body that gathers intelligence on threats. Another went to the city's homeland security ops center. A text message came in from D.C.'s mayor, Muriel Bowser, asking for information. Lanier then set up a conference call with her senior commanders, who were already out in force because of the revelers in town for the city's annual gay pride weekend. Extra resources were deployed into the nightclub district and venues connected to the day's march, expected to draw over 250,000 people. As the sun lit up the Washington Monument, D.C.'s Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency, a 24/7 nerve ganglion of blinking phones, 911 operators, intelligence analysts, computers monitors with incident reports and banks of TV screens with camera views of the city's major avenues and bridges, was pulling in data from all over the region. Metro subway managers, struggling with repairs that shut down some lines, were on alert. Everyone from hospital emergency rooms to the power system and business association had been given notice that something bad was going down 850 miles south and could be coming their way.

"What you would expect," Lanier tells Newsweek of her long morning of putting her many pieces in place. Business as usual for the city's most high-profile, and perhaps popular, official, an instantly recognizable, 6-foot blonde who's often seen behind the wheel of her own cruiser in the city's poorest wards. If the history of terrorism since 9/11 has been a sad litany of "lessons learned," Lanier, who joined the force as a foot patrolwoman in 1990 and quickly rose through the ranks to head its homeland security and counterterrorism division before becoming chief in 2007, is determined to be ready for any eventuality.

Nightclub shooters, like Omar Mateen? Check. Bombers, as in Brussels last year? Check. Anthrax? Check. Nuclear, chemical or biological weapons? Check, check, check.

Unfortunately for Lanier, the recent attacks in Orlando, Brussels and Paris show that you can plan and train until your budget runs dry, and still you rarely stop a determined attacker. "Lone wolves" come out of nowhere. The urban guerrillas of the Islamic State group, or ISIS, use encrypted cellphones. Meanwhile, Lanier knows her city is not just a top-tier target but the greatest unclaimed prize for terrorists. It's the thriving capital of their arch-villain, home to the president who has vowed to destroy them, the Congress that funds the wars against them, the Pentagon that carries out the president's orders and the Supreme Court that helps keep their brethren in Guantánamo.

"Suffice it to say, the capital remains a target," Representative Michael McCaul, chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, tells Newsweek. "They like to return to targets they missed" the first time around, like the World Trade Center, whose garage was merely wobbled by a truck bomb in 1993. "We've stopped several plots against the Capitol," he adds. One case involved pipe bombs and AK-47s; another had drones with explosives. There have been other, more recent plots, he says, but "I'd rather not get into that."

"God willing," a fighter proclaimed in a typical ISIS video from November 2015, "as we struck France in the center of its abode in Paris, then we swear that we will strike…Washington."

One day, Lanier knows, they will come. And despite all her tireless training, surveillance and planning, she knows she can't stop them all.

Billion-Dollar Boondoggle

Washington was still jittery from the 9/11 attacks in the late spring of 2002 when an unidentified small aircraft showed up on radar heading straight for CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, a few miles up the Potomac River from downtown D.C. "I was on the seventh floor. It was late on a Friday morning," recalls Joseph Augustyn, then the CIA's deputy associate director for homeland security. "Somebody runs in and says, 'It's at stall speed. It'll be over headquarters in about eight minutes.'"

Six months after Al-Qaeda hijackers flew airliners into the World Trade Center and Pentagon, officials were on high alert for another such attack, especially since it was only the brave passengers of United Flight 93 who had prevented a hijacked plane from using the National Mall as a big green glide path to fly into the Capitol Building. Washington, D.C., they figured, was Al-Qaeda's unfinished business. The group had demonstrated its patience when it made sure it destroyed the World Trade Center the second time around, on 9/11. F-16s had been flying regular patrols over the city ever since.

Now a plane was heading straight for the CIA, another symbol of American might. F-16s scrambled to look for it, Augustyn tells Newsweek, but they flew too fast and high to see it. The plane kept coming. "It went right over the agency," he says of the previously unreported incident. Secret Service agents raced to small landing strips in Virginia, hoping to find the plane and its owner, but neither could be found. And to this day, Augustyn says, "nobody knows where it landed." (The Federal Aviation Administration tells Newsweek it couldn't find a record of the incident without a firmer date. The Secret Service did not respond by press time.)

The "lesson learned," Augustyn says, is that "you can't send F-16s—you gotta send helicopters." Fourteen years later, choppers of all kinds—from the police, National Park Service, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Customs, Drug Enforcement Administration, FBI and more—constantly flit across the city's skies. In 2013, residents of leafy far northwest Washington got annoyed by loud, unmarked "black helicopters" swirling low and slow over their neighborhoods at night. After much hemming and hawing, officials finally admitted they had been dispatched by the obscure National Nuclear Security Administration to take air samples to help them detect the presence of a future "dirty bomb," an evil marriage of conventional explosives and radioactive material.

"It's not likely, but you can't take that for granted," says Lanier. "I have to be prepared if the most remote kind of attack does occur, so we can continue our operations here."

The city has built up air defenses Saddam Hussein would have envied. From the city-side window of an airliner descending into Washington's National Airport, a discerning passenger can spot some of the Stinger anti-aircraft missile batteries and 50-caliber machine guns potted on the roofs of government buildings around town, including the White House, all of which are backed up by Sentinel phased array warning radar. Air Force F-16s also sit "cocked and locked" at nearby Andrews Air Force Base, deployable at an instant's notice to intercept intruders into D.C.'s Flight Restricted Zone, which extends 15 miles out from downtown.

Yet even with all this high-tech barbed wire, an unhinged postal worker managed to pilot a gyrocopter through the no-fly zone last year, circle the Washington Monument, soar over the National Mall and land on the West Lawn of the Capitol, where millions will gather in January for a presidential swearing-in. His payload? A bag full of petitions for Congress to clean up campaign corruption. Homeland security officials shudder at what else he might have carried. It was yet another "lesson learned." "We fixed that," a city security official assures Newsweek.

How, then, to explain the incident just a month ago, when a Virginia man parked his pickup truck next to the Reflecting Pool, again on the Capitol's West Lawn, and told police he was carrying a bucket of anthrax material that had infected him? Hazmat specialists hosed him down, ran tests and found he was just delusional. But what are police to do on the tourist-choked Mall, security experts ask—stop traffic for random checks?

The U.S. Park Police, responsible for the Mall, "is not staffed or equipped to effectively respond to critical incidents…or protect" such icons as the Lincoln, Jefferson and Washington monuments, its union says. Representative Betty McCollum of Minnesota, the top Democrat on the House appropriations panel with jurisdiction over the Park Police, tells Newsweek the force "has not received the resources it needs, and that concerns me greatly...[g]iven the potential threats to Washington."

The specter of a biological or chemical attack, in not just Washington but many other big cities across the country, has haunted security officials since 1995, when the Japanese Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult uncorked a sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway that killed 10 people and injured 5,000. (The cult was also experimenting with weaponized botulinum and anthrax.) General Charles Krulak, the Marine Corps commandant, surveyed U.S. defenses and was alarmed to discover that not a single federal agency had a chemical and biological incident response unit, so he ordered the corps to set up its own. His fears were realized in October 2001, when anthrax-laced letters were sent to House and Senate office buildings and several media organizations. Capitol offices were evacuated, and Washingtonians, still terrorized by the 9/11 attacks, were frazzled once again.

If the federal government is good at anything, however, it's throwing money at threats. Since 2003, taxpayers have contributed $1.3 billion to the feds' BioWatch program, a network of pathogen detectors deployed in D.C. and 33 other cities (plus at so-called national security events like the Super Bowl), despite persistent questions about its need and reliability. In 2013, Republican Representative Tim Murphy of Pennsylvania, chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee's Oversight and Investigations subcommittee, called it a "boondoggle." Jeh Johnson, who took over the reins of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in late 2013, evidently agreed. One of his first acts was to cancel a planned third generation of the program, but the rest of it is still running.

"The BioWatch program was a mistake from the start," a former top federal emergency medicine official tells Newsweek on condition of anonymity, saying he fears retaliation from the government for speaking out. The well-known problems with the detectors, he says, are both highly technical and practical. "Any sort of thing can blow into its filter papers, and then you are wrapping yourself around an axle," trying to figure out if it's real. Of the 149 suspected pathogen samples collected by BioWatch detectors nationwide, he reports, "none were a threat to public health." A 2003 tularemia alarm in Texas was traced to a dead rabbit.

Michael Sheehan, a former top Pentagon, State Department and New York Police Department counterterrorism official, echoes such assessments. "The technology didn't work, and I had no confidence that it ever would," he tells Newsweek. The immense amounts of time and money devoted to it, he adds, could've been better spent "protecting dangerous pathogens stored in city hospitals from falling into the wrong hands." When he sought to explore that angle at the NYPD, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention "initially would not tell us where they were until I sent two detectives to Atlanta to find out," he says. "And they did, and we helped the hospitals with their security—and they were happy for the assistance."

Even if BioWatch performed as touted, Sheehan and others say, a virus would be virtually out of control and sending scores of people to emergency rooms by the time air samples were gathered, analyzed and the horrific results distributed to first responders. BioWatch, Sheehan suggests, is a billion-dollar hammer looking for a nail, since "weaponizing biological agents is incredibly hard to do," and even ISIS, which theoretically has the scientific assets to pursue such weapons, has shown little sustained interest in them. Plus, extremists of all denominations have demonstrated over the decades that they like things that go boom (or tat-tat-tat, the sound of an assault rifle). So the $1.1 billion spent on BioWatch is way out of proportion to the risk, critics argue. What's really driving programs like BioWatch, Sheehan says—beside fears of leaving any potential threat uncovered, no matter how small—is the opportunity it gives members of Congress to lard out pork to research universities and contractors back home.

When contacted by Newsweek, DHS spokesman Scott McConnell issued a statement calling BioWatch "a critical part of our nation's defense against biological threats." But only on condition of anonymity would a department official claim that BioWatch, "operational 24 hours a day, 365 days a year...has a robust quality assurance program, which includes evaluating and auditing all operational processes from sample collection through final data analysis and results reporting."

The former federal medical emergency official has a succinct reaction to that claim: "What baloney."

Ponder the Unthinkable

The prospect of a terrorist gang heading for Washington with a nuclear weapon—a dirty bomb or the Hiroshima-like device—has kept many a U.S. official awake and staring at the ceiling since the early 1990s, when reports surfaced that Al-Qaeda was trying to obtain uranium with the help of Sudan. More recently, evidence emerged that ISIS operatives in Belgium were casing a nuclear plant; in 2012, two employees of a nuclear plant in the country left for Syria and joined up with ISIS, according to news reports. Such events have prompted U.S. presidents from Bill Clinton onward to funnel untold billions of dollars into systems to head off such an attack, from uranium sniffers around downtown Washington and its Metro system to seagoing drones prowling the Chesapeake Bay and other major waterways and ports for radiological contraband.

With alarming regularity, reports surfaced that the first generation of technology deployed by DHS to inspect cargo from container ships was a bust. The harshest criticism landed on the radiation screeners DHS deployed to ports. Officials had decided to inspect only "high-risk [containers]...actually only 6% of all incoming cargo, leaving the great majority of containers and imports unchecked," the Nuclear Threat Initiative reported in 2007. False positives, from such naturally radiating material as kitty litter, bananas and ceramics, drove operators crazy, "reduc[ing] the sense of urgency among those who respond to them," the NTI said. "Between May 2001 and March 2005, there were reportedly 10,000 false alarms." Despite serious questions about whether DHS was fudging its statistics, Congress allowed it to steer $1.15 billion worth of new business to contractors "to enhance the detection of radiological and nuclear materials." Seven years later, the Government Accountability Office, Congress's investigative arm, found that the new technology was pretty much a bust too. It "did not meet key requirements to detect radiation and identify its source," the GAO said.

Holes like that mean police, fire and health officials must ponder the unthinkable. Jerome Hauer, who ran the Public Health Emergency Preparedness office within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services from 2002 to 2004, says he's not worried about terrorists getting their hands on a ready-made Nagasaki-style plutonium device; he's more worried about them obtaining highly enriched uranium from sympathizers in places like Pakistan, India and Iran—or anywhere there's a nuclear power plant—and fashioning what he calls "an improvised nuclear device," or IND.

Nobody is ready for that. D.C.'s Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency, or HSEMA, concedes as much. Its response plan says: "Emergency responders and hospitals may have limited capability to isolate and treat casualties contaminated with chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and/or explosive (CBRNE) material."

Despite years of thinking about such dire threats, however, the city's mass evacuation plan is still a work in progress, a capital-region emergency planner says. "What they had was only a basic tactical transportation plan. What it showed was all the evacuation routes and basically the stuff they might do in a crisis, such as the police directing traffic," the source confides on condition of anonymity to discuss such a sensitive issue. "But it didn't have an overarching authority, like, when everything hits the fan, what their roles and responsibilities are—that this agency does this, this agency does that, how transport will be mobilized..."

A major lapse was discovered in January 2015, when D.C. Metro passengers were trapped in a smoke-filled tunnel, and first responders couldn't communicate by radio with subway emergency officials. Riders waited for 35 minutes to be rescued. One died, and more than 80 more were injured. "Firefighters resorted to cellphones and a chain of runners to relay information during the Jan. 12 incident," The Washington Post reported, calling it "the latest example of the Washington region's continuing struggles with emergency response, despite spending nearly $1 billion in federal homeland security grants since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks in order to be nimble in a crisis."

Chris Geldart, who took over the HSEMA in 2012, has privately grumbled about the state of D.C.'s preparedness for a major emergency, insiders say, but publicly, he claims he's ready. "We have a mass evacuation plan," he says. "In the past, we had a couple of different plans. Over the last two and a half to three years, we've been making sure that we have a holistic plan. For special events," like the massive annual Fourth of July gathering on the Mall, "we have a walk-out plan. The surface evacuation plan," he adds, "has been in place for a while. But how to move people out of their homes to a shelter or a place outside the city, we're doing a lot of work on that now."

Metropolitan Police Chief Lanier also insists the city is ready. "The surface transportation evacuation plan...has probably been revised five times in the last 10 years," she says. Police will man intersections, synchronize traffic lights and open up "the primary 19 major routes" out of the city.

On June 13, 2008, when Lanier says she had a plan, the combination of a power substation failure that shut off traffic lights and a fire in a Metro station created a massive downtown gridlock that froze D.C. police and emergency crews in the streets. Three years later, when Lanier says the evacuation plan was going through one of its routine revisions, a 5.8-magnitude earthquake rattled the region, casting more doubt on D.C.'s preparations. "Gridlock and confusion" gripped the city, The Huffington Post reported, mostly because the public got mixed messages from federal and local authorities. Longtime D.C. city Councilman Phil Mendelson complained that emergency officials still hadn't gotten the memo from 9/11. Their inability to handle even a snowstorm, he said, was "a blueprint for anybody who wants to commit terrorism in this city." Eight years later, "there's a lot more work that needs to be done, and it's way overdue," says the emergency planner. "There's still no comprehensive plan to move people out of the city en masse."

Another "lesson learned" or, as is usually the case, only partially learned? HSEMA's Geldart says his agency is tight with counterparts in Northern Virginia and Maryland. Yet some D.C. officials seem unsure who's in charge of what during a major emergency. Mayor Bowser is nominally in charge, and she has a deputy mayor for public safety and justice, Kevin Donahue. "The mayor is in charge," his spokesperson says. "Chris Geldart would be coordinating." In reality, as Geldart and Lanier both know, whatever agency responds to the scene of a disaster first—depending on the incident, the D.C. police or the city's Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department—is in charge until local and federal authorities figure out who should take the lead. In the case of a clear act of terrorism, that would be the FBI.

If a dirty bomb were detonated without warning near the White House, there would be "a lot of panic, a lot of chaos," one of Geldart's predecessors, Darrell Darnell, told me in a 2008 interview. But "the conventional explosive itself would be more harmful to individuals than the radioactive material," says the NTI. "Making prompt, accurate information available to the public may prevent the panic sought by terrorists." But as has been demonstrated again and again during D.C.'s confusion over lesser emergencies, downtown intersections, the major avenues to Maryland and the bridges to Virginia would almost certainly be gridlocked as panicked commuters raced for home. Police, not to mention ambulance crews, would be stuck in the streets, unable to get to the radioactive disaster area, much less ferry the sick and wounded to area hospitals. Depending on the size of the bomb and type of radiological material wrapped to it, parts of the federal district could be uninhabitable for years.

D.C.'s first responders and hospitals are better equipped to handle a radiological explosion than they were in 2004, when a startling BBC-HBO docudrama, Dirty War, showed London police and fire crews rushing to the site of big explosion and soon collapsing from radiation poisoning. D.C.'s emergency units are now equipped with hazmat suits and decontamination equipment. D.C.-area hospitals, according to Dr. Bruno Petinaux, co-director of George Washington University's Emergency Management Program, conduct regular drills to stay sharp, including one in May mimicking a mass casualty incident. "We have a designated space to decontaminate patients" by hosing them down, he tells Newsweek. "Other hospitals are doing same." Doctors and nurses are also better prepared to handle chemical and biological attacks from their experience with anthrax, swine flu and Ebola, he says. "I think the medical community as a whole is so much more attuned to picking up these epidemiological" threats. "The D.C. Department of Health," he adds, "established a watch officer position who's available 24/7 and allows us, at 3 a.m. on a Saturday morning, to notify them of an unusual case."

'Your Front-Door Guy Is Bleeding Out'

A little perspective goes a long way in planning, says Sheehan, the NYPD's deputy commissioner for counterterrorism from 2003 to 2008. Pulling off a chemical, biological or nuclear attack is "hard to do," he notes. "Any plots outside the family tend to get rolled up. Plus, fortunately, most of these terrorists are stupid and incompetent—or very limited in scope." He snarks about "terrorism hypers" who have spent the years since 9/11 predicting another big attack in the U.S., something on the scale of the four-day rampage in Mumbai that left 164 dead and over 300 wounded in 2008. But neither Al-Qaeda, nor its mid-2000s offshoot Al-Qaeda in Iraq, nor ISIS, he notes, "has been able to organize a complex, multi-pronged attack inside the U.S. since 9-11." They've been relegated to inspiring "lone wolf" ISIS agents and aspirants to carry out flashy attacks with bombs, grenades and automatic weapons—a far cry from the complex and sophisticated multiple-airliner hijacking operations of 9/11. "None of this is easy, which is why they haven't been able to replicate [Mumbai]," he says. "Guys willing and able to pull off something like that are rare."

Still, New York and other big-city police departments studied Mumbai closely, using table-top exercises and field drills to game out how they might better handle similar scenarios. Paris was also a "game changer" for Lanier's police department, because that city's tapestry of "soft target areas and…a lot of dignitaries" is so similar to D.C.'s. It "caused us to change some of our operations," she says, "some of the tactics of our SWAT team and our first responders." The lessons were applied at the Metropolitan police's new $6 million training facility, which features lifelike streetscapes and buildings for practice.

"You look at every attack, no matter how small or far away, and as quickly as you can," says Lanier, who has a prominent role in the regional Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF, one of 104 around the country), giving her real-time access to the best intelligence the feds have. "We're trying to get those dynamics as they are unfolding, because we don't know if there's not multiple attacks planned for other places. We want to know about the explosives, who are the people involved and their connections, so we can start making immediate protective actions."

The consensus has been that you can't prepare much for "lone wolves" like Omar Mateen, a misfit who claimed loyalty to a variety of militant Islamic groups before unleashing terror with his automatic rifle at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando. Sheehan and other experts say, such attackers are "very difficult to stop once they are ready to launch."

Lanier and her federal partners were thinking about nightclub attacks months ago. In April, they convened a meeting of nightclub owners and restaurateurs in a banquet room around the corner from the White House. "The message was both dire and obvious, once unthinkable and now unavoidable," The Washington Post reported. "You know those terrorists who want to attack Washington? Forget the Capitol. Next time, they might come for your happy hour."

Be ready, the attendees were told by a bevy of police, intelligence and homeland security officials. "As in, who will be in charge if your front-door guy is bleeding out on the sidewalk," according to the Post.

"They can pick their target," Sheehan says of the lone wolves, "and very little can be done about it." But aggressive intelligence operations can break up most plots, he argued in a 2008 book, Crush the Cell: How to Defeat Terrorism Without Terrorizing Ourselves. "Spies are the key!" he says. The FBI, responsible for counterterrorism nationwide, should work more closely with "local police forces that can follow up in the neighborhoods of [suspects] to head off a potential attack," he argues, "before they can be launched."

And the feds should stop spending "obscene" amounts of money "on activities that have a very marginal impact on our safety." The annual intelligence budget has doubled since the end of the Cold War, Sheehan told an interviewer in 2008, from $25 billion, "when we defeated a true strategic threat that had hundreds of nuclear weapons pointed at our cities and control of all of Eastern Europe," to $50 billion, much of that increase spurred by a preoccupation with a few hundred dedicated terrorists.

Lanier is spending on intelligence too, she says. "I have a dedicated field intelligence group. They're out in the field every day." She also gets feeds from the FBI and CIA through the JTTF. "But intelligence comes a lot of forms," she says. "It doesn't just come from an intelligence officer." It can come from cops on the beat or inside the schools, uniformed officers who engage with people. Other experts see only limited value in that, but they say Lanier is constrained from developing more muscular undercover counterterrorism intelligence operations under the nose of FBI headquarters. "The FBI would go ballistic," says one counterterrorism veteran.

Lanier is overstating the number of patrol officers who are actually out on the street at any one time, a recently retired Metropolitan police captain tells Newsweek. "It would scare you if you knew how few police were on the street at any given time," says Robert Atcheson, a 20-year veteran of the force and a former unit commander in the special operations division. "At midnight, there are probably no more than 250 to 300 police officers on the street" out of a total force of 3,600 (not 3,800, he explains; that's an unfilled, authorized ceiling).

Do the math, he says: "Forty percent of the police force is not in uniform or assigned to patrol, which is the only people who respond to a 911 calls or calls for service. The SWAT guys wear a uniform, but they only do SWAT; they don't respond to calls. The crime scene techs wear uniforms, but they don't patrol or respond to 911 calls." The same goes for K-9 officers, detectives and uniforms assigned to homeland security or federal task forces. Subtract another 5 to 10 percent for injuries, sick leave or vacation, plus the 200 unfilled slots, and "your 3,800 starts to look really thin." In fact, it's down to about 1,650. Only 28 percent of that number, he says, work the midnight shift, presumably a good time to throw grenades into a nightclub or drive a truck bomb onto the Mall. That works out to about 450 cops on the street.

When asked about this estimate (without being told the source), Lanier laughs, calls such numbers "insane" and cracks, "You must be talking to a disgruntled union member." (He's not, but she did discipline him and a fellow officer in 2011 for giving Charlie Sheen a high-speed ride from Dulles Airport to a downtown concert date.) "We have about 900 [on the street], but it can be as many on a single shift as 1,200 or 1,300," she counters, "depending on the day of the week and what's going on."

But Atcheson stands by his numbers: "You can't speak truth to power with her," he says. In August 2015, the police union conducted a no-confidence vote on the chief. It passed with 97 percent.

But Lanier has big fans in the higher precincts of the FBI and CIA, where she was a "frequent visitor" after 9/11, Augustyn says.

"Chief Lanier has a no greater fan than me," says Michael Rolince, a former high-ranking FBI counterterrorism official. "She probably has one of the hardest, if not the hardest, chief of police jobs in the country," he tells Newsweek, "just because of what the city is, what it represents, who's here and who travels here, and how the world views Washington, D.C. It is markedly difficult and markedly different than most other major American cities," he says. Pointing to Lanier's years running the Metropolitan police's special operations unit, he adds, "She gets it; she always has."

No matter her talent, however, she'll never be able to protect D.C. to the degree that NYPD Commissioner William Bratton can shield New York, he and others say. "There are just too many moving parts" in D.C., as Augustyn puts it, too many federal and local government agencies and jurisdictions with their own homeland security agendas.

Augustyn, who joined the Jefferson Waterman international security firm after retiring from the CIA, says he was astonished by the radio failures during the fire in the Metro tunnel last year. He thought D.C. officials fixed that problem long ago, taking their lesson from the 9/11 radio failures at the World Trade Center. "I thought, for all the training…you have to wonder where the money's been spent."

Lanier had no role in that disaster, but she suggests her agency wouldn't fall down the way the fire department and Metro officials did. "Maybe I'm a little biased, but when you talk about [police in] the top-tier cities—New York, L.A., Washington—I think we are the most advanced in a lot of ways, but the most advanced in terms of preparation and response as any law enforcement agency in the country." She stops and then adds, "We have to be."

On that, at least, everybody can agree. Yet despite the bulked-up Metropolitan police presence on pride weekend, a vandal managed to spray-paint anti-gay graffiti on a sidewalk in Dupont Circle, the 24/7 action center for the city's LGBT community. Thousands of revelers had gathered in the neighborhood that night.

It could have been far, far worse.

This story was updated to include a paragraph on the U.S. Park Police and the security situation at the Washington Mall.