At 34, Serena Williams is old for a tennis champion. The cartilage in her knees has started to wear away, so the bones rub against each other when she runs. In June, she lost the French Open final to a relative newcomer, 22-year-old Spaniard Garbiñe Muguruza, after struggling with a thigh injury. At this stage in a career, most professional players retire, at peace with the idea that they can't continue competing for Grand Slam titles.

But Williams, the top-ranked woman in the world, isn't thinking about retiring. Instead, when she steps onto the grass courts of Wimbledon for her first match of this year's tournament in late June, she will likely be thinking of a woman who hasn't played professional tennis for almost 17 years. On August 13, 1999, Steffi Graf ended her career at the age of 30, having won a record 22 Grand Slam titles, including that year's French Open. No woman has won as many Slams since professional players first went up against amateurs in 1968. Less than a month after Graf retired, 17-year-old Williams won the U.S. Open, the first of her 21 Slams. Two more and she'll be, on paper at least, the greatest women's player in history. Williams's body might be begging her to let go of that dream, but she isn't listening.

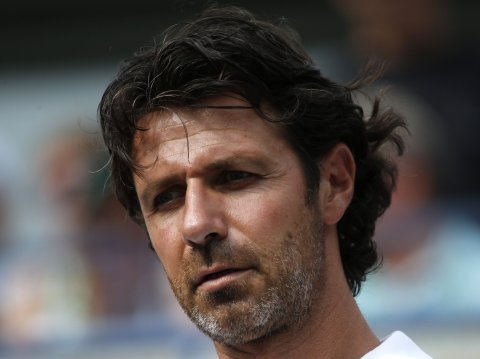

To overtake Graf, Williams will need something special. Or some one special. Williams's coach, Patrick Mouratoglou, believes he is that someone. Mouratoglou, a wealthy Frenchman who had not coached a big-name player before he took over from Williams's father, Richard, as her coach in 2012, tells Newsweek he can help Williams be the best in the world for several more years. But Mouratoglou is a controversial figure, and many in the game say his coaching record prior to Williams was average, and his current success is purely because she is an extremely talented and driven athlete. That criticism makes Mouratoglou more determined to help Williams get over the line. If she does win two more Grand Slams, Mouratoglou will go into the record books with her, perhaps finally quieting the naysayers who have plagued him his entire career.

Meeting Mouratoglou

The relationship between any professional tennis player and his or her coach is easily broken because players hire their coaches directly, paying their salary as they would for any other employee. The coach is cast in the role of mentor and taskmaster—but both parties know that the coach is really just the help. And many do not survive very long. Brad Gilbert, Andre Agassi's longtime coach, whom the former men's world No. 1 described as "the greatest coach of all time," stayed just 16 months with the current men's No. 2, Britain's Andy Murray. Failing to elevate a player's ranking can cost a coach his or her position. Ivan Lendl, a former No. 1 player turned coach, said of the dynamic that it helps to be "independent of needing the job." Lendl, of course, can afford to be fired.

Before Williams hired Mouratoglou, she'd had only two coaches—her mother and her father. The latter was the more involved, a disciplinarian who could stand up to his sometimes irascible daughter. (In 2009, the Grand Slam Committee, made up of the heads of the four Slams, put Williams on probation for two years after she threatened to shove a ball down a lineswoman's throat.) So when Williams decided she wanted a new coach, Mouratoglou knew he had a difficult job. "[Do you] think it's easy to deal with Serena?" he asks, sitting near the clay courts at his new tennis academy in Nice, France. "Do you think it's easy to find a way that Serena follows you?"

In 2012, Williams needed help finding her way; she was in a slump. She had won two Grand Slams in 2009 and two more the year after that. But in 2011, she missed half the season due to a foot injury and blood clots in her lungs. In the U.S. Open final that year, she again lost her temper, saying to the umpire, "You're a hater, and you're just unattractive inside." Williams ended the year without a Grand Slam title and slid down the women's tennis rankings from fourth in the world to 12th.

Over the first five months of 2012, her dip in form continued. At the Australian Open in January, she lost in the fourth round to Ekaterina Makarova, then the women's No. 56 and the lowest-ranked player of the 16 athletes remaining in the tournament. In May, Williams crashed out of the French Open in the first round, losing to Virginie Razzano, ranked 111th in the world.

After that tournament, Williams went to Mouratoglou's academy in Paris, the precursor to his school in Nice. At the time, Mouratoglou was relatively unknown, serving as coach to Grigor Dimitrov, then ranked No. 37 for men. He says Williams was in Paris, needed somewhere to practice and vaguely knew of him. On her first day at the academy, Mouratoglou says, he watched Williams practice for 45 minutes and then gave her his assessment. "You lack balance. Every time you hit, you're off balance, which makes you miss a lot," he says he told her. "Also, you lose power because [your] body weight doesn't go through [the shots], and you're not moving up, so your game is slow. Usually, you play fast."

Mouratoglou says Williams said, "Incredible, my father says exactly the same. Let's work on it."

Mouratoglou and Williams trained for the rest of the week before she returned to the U.S. Then, the week before Wimbledon, she called Mouratoglou and asked to try him out as a coach during the tournament. She hadn't won a Grand Slam in two years, she said, and, convinced that her career would soon be over, she wanted to win just one more.

Mouratoglou agreed, and Williams has been nearly unbeatable since. That year, aged 30, she won Wimbledon, an Olympic gold medal and the U.S. Open. In February 2013, she regained the No. 1 ranking, becoming the oldest woman to hold the top spot, and that year she won the French Open and the U.S. Open. In 2014, she was still No. 1 and again won the U.S. Open. In 2015, she won the Australian Open, the French Open and Wimbledon.

Mouratoglou isn't shy about taking credit for Williams's fight back and says his strictness with her was pivotal. In his 2015 autobiography, Le Coach, he recounts once slapping Williams's hat with his hand when she was ignoring him, telling her that if she wanted him to coach her, she would have to show him respect. "I think it's important to be firm and to have personality," he says. "[Players] want someone strong next to them, because you give [them] confidence like this."

Part of Mouratoglou's willingness to stand up to Williams may stem, like Lendl, from not needing the job. His father, Pâris Mouratoglou, is the former chairman of EDF Énergies Nouvelles, and in 2011 he sold his 25 percent stake in the company. Despite hoping that his son would follow him into the business, he gave the 26-year-old the money to set up his own academy in 1996. Mouratoglou was able to hire veteran tennis coach Bob Brett to head the school and give it legitimacy. It was Brett who taught Mouratoglou how to coach.

The academy now hosts more than 2,000 players a year, enticing many with its star, Williams. She is the only person Mouratoglou coaches, and their association is believed to extend beyond the courts. It is rumored that they have been romantically involved, something that Williams's former rival Maria Sharapova publicly hinted at in 2013. Following a Rolling Stone article in which Williams seemed to take a dig at Sharapova and her then-boyfriend, Grigor Dimitrov, the Russian player, who was recently banned for two years after failing a drug test, commented, "If she wants to talk about something personal, maybe she should talk about her relationship and her boyfriend that was married and is getting a divorce and has kids."

Photographs of Williams in 2012 with her hand in the back pocket of the then-married Mouratoglou's jeans had already prompted rumors about their relationship. Mouratoglou claims he has not seen the photos, although he does not deny he and Williams were, or are, a couple. "Maybe she didn't know where to put her hand," he says. A representative for Williams declined to comment.

Middling record, criticisms

Whatever the nature of Williams and Mouratoglou's personal relationship, it has run parallel with the most successful period of her career. And that has made Mouratoglou famous. The coach now likes to compare himself to Manchester United's new manager, José Mourinho, one of the most successful soccer coaches of his generation. But Mouratoglou's critics—and there are many—say coaching Williams is hardly difficult.

"Coaches who have taken players from 25th in the world to the top five—that's coaching," says someone involved in the industry, who asked not to be named for fear of jeopardizing his professional relationships. "Credit to whoever taught [Williams] how to serve, but that's it." (Commentators consider Williams's serve, which her parents helped her develop, her greatest shot. Graf said of it, "I think that's the biggest weapon there has ever been in the sport.")

Such criticisms clearly irritate Mouratoglou. "I think to work with her or Novak [Djokovic] or Roger [Federer]—I think there are three guys in the world who can do that," he says.

Mouratoglou's critics see his unwavering self-belief as arrogance. "He thinks he's the god of tennis," the source says. "Coaches [who] think they're the stars—there's only one star, and that's the player. But you do the math: Look at his coaching record before Serena."

Before he met Williams, Mouratoglou's most successful partnerships were with the mid-ranking players Marcos Baghdatis, Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova, Yanina Wickmayer, Aravane Rezaï, Jérémy Chardy and Grigor Dimitrov. Only Pavlyuchenkova lasted with him beyond a year, and, apart from Wickmayer and Rezaï, all achieved higher rankings once they left Mouratoglou.

Mouratoglou says he fired the players, with the exception of Dimitrov, who left when Mouratoglou began coaching Williams. "Most of the time, they were not prepared to do the extra effort to go to the next level, which is something I'm not judging. I'm fine with that," he says. "I just told them, 'Do what you want to do,' but my goal, I want to be at the top of the game as a coach, so I'm not going to wait. I'm going to do something else."

Most of Mouratoglou's former players did not respond to Newsweek's requests for comment or declined to respond. Rezaï, however, tells Newsweek that her relationship with Mouratoglou ended when the pair fought over his coaching style, which she found too demanding. "He gave me a diet to lose, I don't know, 6 or 8 kilos [of weight] when I was playing tournaments," she says. "The way that he was training me or other players, it was too extreme, too hard. Players never really worked with him for more than a year because the way that he worked. It's not compatible in the long term. He broke the players."

Mouratoglou doesn't dispute that his methods can be harsh. "Aiming for the top of the game is really tough," he says. "That is the reason why only a few can make it. Serena is willing to do it, and that is one of the things that make her different."

Rezaï disputes this, saying that Mouratoglou is not as severe with his star player because he's afraid of getting fired. But Williams still follows a fairly punishing training regimen. She and Mouratoglou train for about two hours a day on the court, with another four hours devoted to her overall fitness, physiotherapy, yoga and stretching. Days off, Mouratoglou says, are rare.

When Williams is not training, she likes to watch videos of the top male players and asks Mouratoglou to help her emulate their techniques. "She wants to improve," he says. "How can she improve looking at women? She's the best in the world."

But that kind of focus and ambition can't overcome the physical decline that comes with age. Williams failed to win the last Grand Slam tournament of 2015, the U.S. Open, when she lost in the semifinals. In November, Mouratoglou made headlines when he said of Williams, "The [knee] cartilage is [almost] gone, not all of it but a big part. She has bone bruises, and if you keep on playing with this for too long, the next step is a stress fracture."

Mouratoglou now walks back that assessment. "There is no problem [with the knee], and if she wants to play for five years, she will play for five years," he says. But in January, Williams was forced to pull out of the Hopman Cup, a relatively minor tournament, after suffering from knee inflammation. Soon afterward, she lost in the final of the Australian Open. Although Mouratoglou says Williams and her team have found medical solutions to deal with her lack of cartilage—which he says Williams doesn't want made public—he eventually acknowledges that the bones in her knees "are knocking together. Doing sports every day for so many years, you know, your body gets old. Simple."

Williams's defeat in the final of the French Open, her third consecutive Grand Slam loss, may be a sign that her career is finally on the decline. After the match, Billie Jean King, a former women's world No. 1, said Williams didn't seem happy on the court. "She doesn't have the same vim and vigor. I don't know if it's physical, but something's not quite right," King said.

Mouratoglou thinks that pressure to equal Graf's record caused Williams to lose the match. "There is big pressure, and if we say there's no pressure, it's a lie," he says. "To be able to fight against it, you need to have confidence." After Williams's defeat in Paris, Mouratoglou reassured her that she did have the physical strength to win Wimbledon; she just needed to believe in her own capabilities. "I feel that we've found this," he says. "She's realized that there is nothing stopping her from winning the next Grand Slam."