June marks the beginning of summer, but it hasn't been a vacation for Donald Trump. The presumptive Republican nominee has seen his negative poll numbers rise higher than one of his skyscrapers: Seventy percent of Americans have a dismal view of the mogul, according to the ABC News/Washington Post poll that appeared in mid-June. Trump needs to be generating enthusiasm among Republicans, especially the elected officials he'll have to lean on as surrogates and allies come autumn.

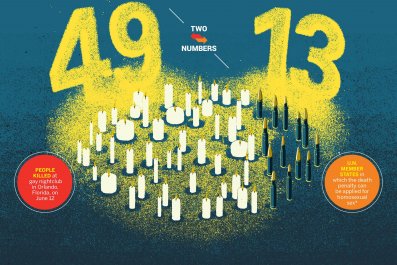

He's trying to right the ship. On June 20, the mogul parted ways with his campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski. The little-known New Hampshire operative, known internally for his temper and running afoul of other Trump officials, was probably best known to the public for his altercation with a young reporter that led to battery charges that were later dropped. After Lewandowski's departure was announced coldly—he was said to be "no longer working" for the campaign—a Trump adviser tweeted, "Ding dong the witch is dead." It's unlikely that Lewandowski's departure will end Trump's standoff with GOP leaders. After the Orlando, Florida, massacre, an exasperated Trump told Republican leaders to "be quiet" and that he could win "alone."

The senator who has stayed closest to Trump is Jeff Sessions, the first in the chamber to endorse him. He offered only a gentle rebuke for Trump's criticism of the Mexican-American judge overseeing one of the suits against Trump University. "Well, it would've been nice if it…had not been said, for sure," Sessions told NBC News. That was the extent of his criticism and that was the point: stay close to Trump and help stomp out the fire.

The Alabama lawyer and Manhattan mogul make for an odd couple. Sessions is as courtly as Trump is brash; as Southern as Trump is New York City. His full name couldn't be more Dixie: Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III. And he's as maritally stable—47 years to his wife, Mary—as Trump has been peripatetic. What brought the two men together is their views on immigration. Sessions has fought against any path to citizenship for those in the U.S. illegally, and he wants to curtail legal immigration, just like the wall-building Trump. Sessions knows that making the economic case against immigration is going to be a lot more helpful than conflating immigration issues with a judge's ethnicity.

Does this mean Sessions could be the reality-TV star's running mate? It's unlikely Trump, 70, would tap the silver-haired, 69-year-old Sessions. That would make for the oldest ticket in American history. Besides, Sessions is not a world-class orator and lacks the attack-dog instincts most nominees want in a veep. Sessions's value to Trump is that he is arguably the closest thing the fiercely irascible and independent developer has to a wise man.

The Working Man's Favorite Private Jet

Last August, the Trump campaign was just two months old, and the punditocracy was dismissing the New Yorker's presidential bid as the summer infatuation of disgruntled voters—one that would end in September, when Republicans snapped out of their dour mood and embraced a staid, established pol like Jeb Bush. But one event that month began to shake the consensus that Trump's campaign was a mere blip. It was a rally in Mobile, Alabama, where an estimated 30,000 supporters piled into Ladd-Peebles Stadium. Save for Mardi Gras, "it was one of the greatest events Mobile ever put on," the city's deputy mayor said. As the crowd waited for their candidate, loudspeakers directed the throngs to look up as Trump Force One did a circle over the stadium. The place erupted.

When Trump mounted the stage not long afterward, the crowd was surprised to see Sessions on the dais. They again cheered wildly. Sessions is popular in Alabama, having run unopposed in 2014 for his third term in the Senate. When Trump touched on anchor babies—the pejorative term for children delivered in the U.S. just to gain citizenship—the crowd howled. The spectacle showed that Trump had a base and a powerful bat to swing.

In Alabama, Sessions's Trump-esque stand on immigration is popular with rank-and-file voters, although businesses dependent on unskilled labor (such as agriculture) or more highly educated immigrants (the aerospace industry around NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville) have been disappointed by him. But Sessions has made it clear he won't budge on immigration. Good at bringing home money to Alabama, he's able to take the hit on this issue. That can partly be explained by the fact that while his immigration stance isn't very different from Trump's, his pitch isn't as belligerent, not nearly as off-putting. Sessions is less inclined to portray immigrants as a cultural threat than he is to stress economics. A surplus of immigrant labor is "sapping the wages" of Americans, he says, be they white, black or Hispanic.

It's an argument he was making long before Trump called for that free wall. In 2013, Sessions was the most outspoken Senate opponent to the bipartisan immigration bill favored by the likes of Florida Senator Marco Rubio and cheered by the Obama administration. It would have given those in the country illegally a path to legal status, and Sessions, the ranking member on the subcommittee with jurisdiction over the issue, dug in against what he said were elites who favored cheap labor. "We were not elected to clamor for the affections of Washington pundits and trendy CEOs," he told his fellow Republicans. The immigration bill passed the Senate but died in the House.

The debate helped strengthen ties between the glitzy Trump and the generally quiet and genial Alabaman. The two met in 2005 after Trump was quoted lambasting the high cost of refurbishing the United Nations headquarters in New York. (Naturally, Trump said he could do it cheaper.) The two kept in touch, and when Trump began his presidential bid a year ago, they began to speak often. In February, six months after that big rally in Mobile (which helped Trump going into the slew of Southern primaries), Sessions became the first senator to back him and one of the few who haven't hemmed and hawed in recent months.

Sessions's support isn't just perfunctory: His allies are advising the campaign, and one of his top staffers, Stephen Miller, is a top policy adviser for Trump who also serves as a warmup act at some Trump rallies, putting the crowd into the properly angry mood by reciting bleak statistics on the manufacturing situation in their local community. "I have tremendous respect for Senator Sessions. He is a terrific person, a great leader, and I am so grateful for his support," Trump told Newsweek via email.

The Fight for the Noncollege White

No one looking at Sessions's up-from-rural-Alabama life story probably would have guessed that he'd end up the pol closest to the Manhattan tycoon. "In another life, he wouldn't care about Donald Trump, but he is enjoying it this time because he and Trump agree so strongly" about immigration, says an old friend of Sessions's, who thought the senator would object to his talking to reporters. He also noted that the soft-spoken lawyer's backstory is very different from Trump's. Sessions grew up the son of a shopkeeper in rural Alabama, attended a small Methodist college and was settled into a career as a federal prosecutor when Ronald Reagan tapped him to be the U.S. attorney for southern Alabama in 1981. Five years later, the Gipper nominated Sessions to be a federal District Court judge, but controversies—from alleged racial slights to his subordinates to his prosecution of civil rights workers on charges of voter fraud—turned a routine judicial appointment into an alley fight. Led by Joe Biden, then the ranking Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee, the panel voted against Sessions's confirmation. Two Republican senators joined the Democrats in voting against him, although one of them, Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, later said he regretted that vote.

Ironically, Sessions went on to become a colleague of some of the folks who blocked his judicial appointment. He won election as Alabama's attorney general and in 1996, a decade after his nomination was poleaxed, he won the U.S. Senate seat vacated by retiring Democrat Howell Heflin, who fought his becoming a judge.

Now, increasingly nervous Republicans on Capitol Hill hope Sessions will help Trump right his campaign, although they know Trump has no Rasputin and values the opinions of a precious few, his daughter Ivanka among them. That latest ABC News/ Washington Post poll had some ominous news about Trump's support among white working-class voters, the backbone of his support in the Republican primaries and an essential bloc if hopes to be competitive this fall. The survey found that Trump's favorable rating among noncollege whites has gone from a plus-14 in May to negative minus-7.

Still, that's a group Sessions knows how to reach. It might horrify liberals that Sessions, rated the fifth most conservative member in the Senate, could help dig Trump out of this hole by helping to hone his jeremiad on immigration. But it's hard to find anybody else willing or able to do what's needed to make Trump if not great then at least viable again.