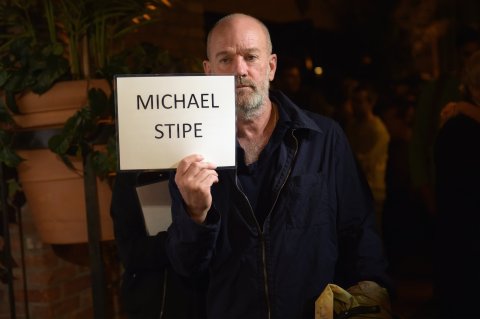

Michael Stipe is offering me anchovies.

"This is not what I expected," the retired rock star says, poking at the plate of thin fish he's just ordered at a seafood bar in New York City's East Village. "Do you eat anchovies?"

This is not what I expected either: being served seafood by the ex-frontman of R.E.M. I politely decline, citing vegetarianism.

"I'm vegan-default," Stipe says, laughing. "I like these little fishies." So...a pescetarian? "No, I eat anything. But most of the time, I'm vegan." He swore off meat as a teenager but "started eating everything again when I was 40."

Aging plays strange tricks. And aging is on both of our minds: Stipe is a 57-year-old man looking back at the reluctant 32-year-old superstar who made Automatic for the People, the 1992 release that's commonly cited as R.E.M.'s melancholy masterpiece. He's looking back, in part, because that album is being reissued in deluxe format this month to mark its 25th anniversary. "I'm kind of in awe of what we did as relatively young men," he says. "I mean, we started very young. It's intense."

It's fitting, then, that Automatic is overwhelmingly preoccupied with mortality. Among its most enduring tracks are the end-of-life meditation "Try Not to Breathe," the grief narrative "Sweetness Follows" and, of course, the popular anti-suicide plea "Everybody Hurts."

For Stipe, it's "super weird" to revisit this milestone now that R.E.M. is no more. "It makes me feel like Father Time," he jokes. Not that he looks the part (anymore): Stipe's long beard—the mountainous ZZ Top–worthy facial hair that became a fixture in 2016—is finally gone. Wearing white slacks and a white button-down shirt, the singer is in a chatty, jovial mood. Nothing is off-limits; every R.E.M. song I mention prompts a story or some unconsidered insight (on "Ignoreland," a 1992 rant blasting the GOP, for instance: "The production could have been a lot angrier"). It's a Tuesday afternoon in October, and Stipe has just finished a taped interview with Dan Rather, whom he identifies in an Instagram caption as "Hero."

The early 1990s were remarkably eventful for R.E.M. In 1991, Out of Time, the band's hugely popular seventh album, ushered in a brighter, more orchestral sound and shot to No. 1 on the strength of "Losing My Religion." The nerdy college-rock band from Georgia was now as famous as Madonna. "Suddenly, I was a celebrity," Stipe says, someone who got recognized on the street. "It went to a different level because of MTV." He lip-synced for the first time in the "Religion" video, ending a long-standing R.E.M. policy. The singer decided to give it a try after seeing Sinéad O'Connor's "Nothing Compares 2 U" video. "Prior to that, I had thought, This is incredibly stupid, and everybody's in on the joke, and you just look like a moron."

At that year's Grammys, R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck wore garish casino-themed pajamas as a gag because he didn't expect to win. The joke was on him: R.E.M. got three awards. "What [1991's success] brought to us as a band was this incredible confidence to jump off a cliff together," Stipe says.

Instead of touring behind Time, R.E.M. went into the studio with a string section and quickly made Automatic, a largely somber counterpoint to Time's pastoral pop. It's one of those indelible records that captures a great band at the peak of its powers. A quarter of a century later, it remains perhaps the most elegiac rock album to have sold 18 million copies.

Related: Reflecting on R.E.M.'s most misunderstood album with Michael Stipe

Considering all that glitzy success, what explains the album's downbeat tone? "We had just come through the 1980s," he says. "Reagan and Bush and AIDS. It was fucking dark times. And this record is a dark record."

There were personal losses too. "My grandparents were at the end of their lives. I had a sick dog. Conflating a sick dog with the AIDS crisis is obviously dangerous territory, but this was what I was dealing with on a day-to-day basis. And the '80s were just fucked up. So many people dropped off and disappeared and died. I don't know. I hit 30. I guess you think about things differently."

'I'm Not Normal'

John Michael Stipe was born into a military family at the dawn of the 1960s. Despite being yanked from state to state by his father's military career—Texas, Illinois, an army base in Germany—the singer has said he had an "unbelievably happy" childhood. Stipe rarely discusses his early life in interviews, so I'm surprised when he starts talking about his father. "He was an astonishing man. But he was weird. He had this darkness, and he had this oddness."

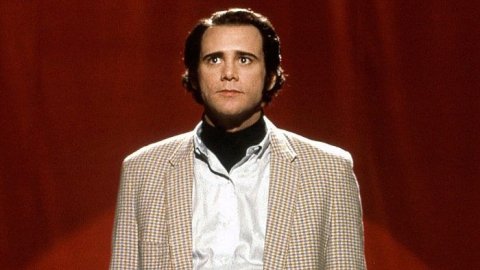

When Stipe was 15, he saw Andy Kaufman on television and felt a flash of recognition. It was 1975. The comic was deep in character as "Foreign Man" during the first season of Saturday Night Live. Stipe was struck by the incomprehensibly weird irreverence of the bit. "I was like, 'This is insanely fucked up. This is really not right,'" he remembers thinking. "[Kaufman] was addressing for me, as a teenager, what CBGB and punk rock and Patti Smith and Tom Verlaine [would represent]. This was my island of broken toys."

Stipe was living in East St. Louis at the time, and now he felt seen. "Andy Kaufman and punk rock: Suddenly, I found my tribe. These people are like me. This is what I'm going to do." Stipe was also discovering his sexuality (he came out as queer in 1994) and "realizing that I was really different from anybody else. But I'm not normal anyway. I'm a little bit odd."

After high school, Stipe lived with a punk band in Illinois, subsisting on spaghetti and butter because they couldn't afford real food. He soon moved to Athens, Georgia, to attend the University of Georgia, where he met future bandmate Buck at the record store where the guitarist worked. They decided to form a band with fellow UGA students Mike Mills (bass) and Bill Berry (drums). The rest is college-rock history. Murmur, the band's inscrutable debut, arrived in 1983, Reckoning in 1984 and so on.

Stipe's lyrics were famously cryptic, his delivery confounding. "Murmur is a complete mystery to me," the singer says. "I went into the studio with no idea what to do except what I did in a small club from the stage. That was to sing nonsense words strung together that had a lot of emotive power." He grew tired of people asking what the songs were about, "because I didn't know. They were just feelings."

As the band found mainstream success, Stipe's hazy lyrics swam into focus. Years later, the singer's obsession with Kaufman resulted in the beloved R.E.M. song "Man on the Moon." An affectionate send-off to the comedian, who had died (or so we think) in 1984, "Moon" is Stipe's favorite song on Automatic: "I always like songs that people like to sing along to." Curiously, it is also one of two songs written about tragic celebrity figures of ambiguous sexual orientation: "Monty Got a Raw Deal" addresses the life and death of actor Montgomery Clift. When I mention the track, Stipe launches into a story about meeting Clift's onetime co-star Elizabeth Taylor at Elton John's birthday party. He told the elderly actress about the song. She grabbed his hand—Stipe grabs mine sharply in imitation—and said, "The love that we had was more powerful than any love I've ever known. There was no name for it then, and there's no name for it now."

In 1992, Stipe, like Clift long before him, was coping with the perils of newfound fame and the prospect of publicly acknowledging his queerness. Rumors (false) swirled that he had contracted AIDS. "That was dismaying, because I didn't feel like it came from a place of true concern," he says. "I felt like it was more petty rumormongering."

When Stipe finally addressed his sexuality in 1994, he was promoting the louder and flashier R.E.M. album Monster. Grief—and the darker side of celebrity—still absorbed his songwriting. "Let Me In," that album's centerpiece, finds Stipe wailing about the then-recent suicide of his close friend, Kurt Cobain. It's like the harrowing "Everybody Hurts" complement nobody wanted and everyone needed. "I've had more than my fair share of suicides," Stipe tells me. "I'd like to have no more."

That Orange Clown

In 2015, Donald Trump, then a long-shot presidential candidate, used R.E.M.'s 1987 hit "It's the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine)" as entrance music at a GOP rally. Bad idea. Stipe's denunciation came hard and swift: "Go fuck yourselves," the singer told Trump's campaign in a statement. "Do not use our music or my voice for your moronic charade of a campaign." (Mills joined in the disgust, calling Trump an "orange clown" on Twitter.)

It was classic Stipe: strident, liberal, anti-establishment. It was also a show of artistic and political unity by the members of R.E.M., four years after the band amicably broke up.

Stipe was never shy about sharing his political views, especially during the Automatic era: This is the rock star who wore a "White House—Stop AIDS" hat to the 1992 Grammys. Post-R.E.M., his political advocacy has only intensified. He has spoken out against the "unjustifiable" treatment of U.S. military secrets leaker Chelsea Manning and joined with Elton John to support transgender inmates in Georgia. In 2016, he became a vocal supporter of Bernie Sanders, often introducing the senator at rallies. Stipe and Sanders were once pictured eating hot dogs together at Coney Island.

Are they friends? "No, not friends! We don't exchange text messages or anything." But Sanders was the outsider candidate, "so of course I ended up with him. You're talking to the guy who wrote 'Everybody Hurts,' but I consider myself an outsider."

Stipe despises Trump and feels "personally insulted" by the country's sharp political swing to the right. "I'm a hippie," he says. "My generation was going to solve the problems of energy efficiency and the environment. And look where we find ourselves. We're at the brink of absolute collapse. My generation has done the exact opposite of what I thought it would do."

The singer takes solace in artistic ventures: sculpture, photography, video portraits, music. He recently produced a forthcoming album by the electronica duo Fischerspooner. He has an autobiographical book of photographs coming out in 2018. "I don't even like talking about it, because when I read about it, it seems like, You pretentious twat! Just go fucking write a song again. I imagine other people reading that and going, Shut up!"

Musical appearances have become less rare for the rocker: In 2016, he took part in a pair of David Bowie tribute concerts. In November, he plans to take the stage at Carnegie Hall alongside friend Patti Smith as part of a benefit concert for climate action.

And then there's the R.E.M. reissue project. Out of Time got the 25th birthday deluxe treatment in 2016. Monster is due for a reissue in 2019. And Stipe's favorite R.E.M. album, the sprawling New Adventures in Hi-Fi, should follow two years later.

The Automatic reissue package comes with a 60-page book of photographs, but for hardcore fans, the real treasure is the bonus disc of unheard demos and lost tracks. I bring up "Devil Rides Backwards," a mythical outtake—raw and unfinished—that's been unearthed, and Stipe flinches: "Did you see that little stroke that just happened in my right eye?" He still can't bring himself to listen to the demos. Just thinking about it gets him a bit agitated. "I listened to like four of them and was like, this is excruciating. I felt like I was being flayed alive."

He enjoys reintroducing the band's music to the world—just not in the form of a reunion tour. (I had to ask, though it might have sounded more like a plea than a question.) "That'll never happen," Stipe says plainly: no wavering, hemming or hawing. "I can't think of a single thing that could make us come together to do anything publicly."

Why so certain? "Because we did what we did. To try to put the band back together for any reason would just be sad and wrong."

Would he ever make a solo record? "I don't even know what a solo record is these days. So the answer is no. But I want to use my voice again. I really like it."