Uber's fight to operate in London starkly shows how artificial intelligence (AI) can quickly eviscerate the value of hard-earned human knowledge. The city's move to boot Uber is not much different from Donald Trump rejiggering environmental rules to help American coal miners keep their jobs. We are now asking a hard question of society: Do we want government to protect us from having our employment outlooks narrowed to working as overeducated TaskRabbit serfs putting together other people's Ikea tables?

Uber is in court appealing an order that would kick it out of London, where city officials ruled that Uber drivers are not safe enough and—even worse to the British—too rude to be allowed on London's streets. Uber's new CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, has apologized to Londoners for "messing up" and hopes to make amends.

But London's ruling is only tangentially about Uber's reputation as an asshole company. It's really to protect a generation of local taxi drivers who have invested enormous amounts of time and personal wealth in filling their heads with what is now nearly useless information.

Anyone who wants to get a license to drive one of London's black cabs has to master what's famously called the Knowledge, which is one of the most ridiculous mental challenges ever imposed on people who will wind up making about $60,000 a year. A prospective driver has to memorize every street, building, park, statue and trivial landmark in central London, and be able to perfectly recite the fastest route between any two spots in the city. The test is so difficult that brain scientists have studied the city's cab drivers and discovered that the memorization gives their brains an enlarged posterior hippocampus, which apparently is not painful.

The requirement for the Knowledge has been in place for more than 150 years. It long made sense in an agonizingly complex geography, where a wrong turn could leave a driver lost in a maze of medieval streets. Mastering the Knowledge means studying 40 hours a week for two, three or even four years. The only way, then, for London to have enough cab drivers—because who would want to go through this?—has been to guarantee they'd be paid decently. As a result, London has the highest taxi fares in the world.

Enter Uber, which navigates with GPS. When a driver picks you up, your destination is already on the driver's phone, which can dictate turn-by-turn directions. Without GPS, no car service could compete with the efficient routes of a Knowledge-able black cab driver. But with GPS, even immigrants new to London can navigate the city well enough. In the past couple of years, the AI-based app Waze has taken this capability to another level. Waze learns from the movement of all Waze users in a city, constantly finding better routes, understanding traffic patterns and knowing about jams and accidents in real time. Now a new driver can outshine a veteran driver by simply downloading an app. Getting started requires no huge sunk costs, no grueling hours of study. So these upstart drivers don't need the guarantee of high wages for life. That means they can underprice black cabs.

London's black cab drivers are watching technology sweep away their livelihoods. The loss they feel is growing familiar across other professions. "I'm upset because what I had to go through now comes on your phone," Mick Smith, a London cab driver for 28 years, told CNET. "It's not about competition—it's about going through the same process." It's an understandable reaction but also unrealistic. AI has made that process unnecessary. Even crueler, the knowledge Smith built up of London's streets isn't useful for much of anything else.

This is happening to more and more professions. Goldman Sachs and many of the biggest hedge funds are all switching on AI-driven systems that can foresee market trends and make trades better than humans. One Goldman Sachs trading office has been whittled from 600 people to two. AI can read X-rays better than radiologists. A great deal of the work done by lawyers is heading for the AI trash bin. Like the Knowledge, these are professions that require loading up your head with a lot of data and rules, and then mostly just executing. AI can do that now.

Of course, there's another side to this. AI is making all these services cheaper and easier to access. Uber brought cheaper rides to London. And hey, if we could all get a lawyer in an app, who but the lawyers would be crying? Those who invested in obtaining their knowledge get hurt, but many more people benefit. Is that bad? When are jobs for a few more important than economic or other upsides for many? Figuring that out is going to tie lawmakers in knots for a generation.

Then again, Uber in London shows how AI can open opportunities for those who partner with the technology rather than fight it. You want to be an Uber driver armed with Waze, not a traditional driver insisting your brain alone is better. You want to be a radiologist who can harness AI to make faster, more accurate diagnoses, or the lawyer who focuses on creative legal arguments while deploying AI to do all the grunt case research. As futurist Kevin Kelly puts it in his book The Inevitable, "Our most important thinking machines will not be machines that can think what we think faster, better, but those that think what we can't think. You'll be paid in the future based on how well you work with robots."

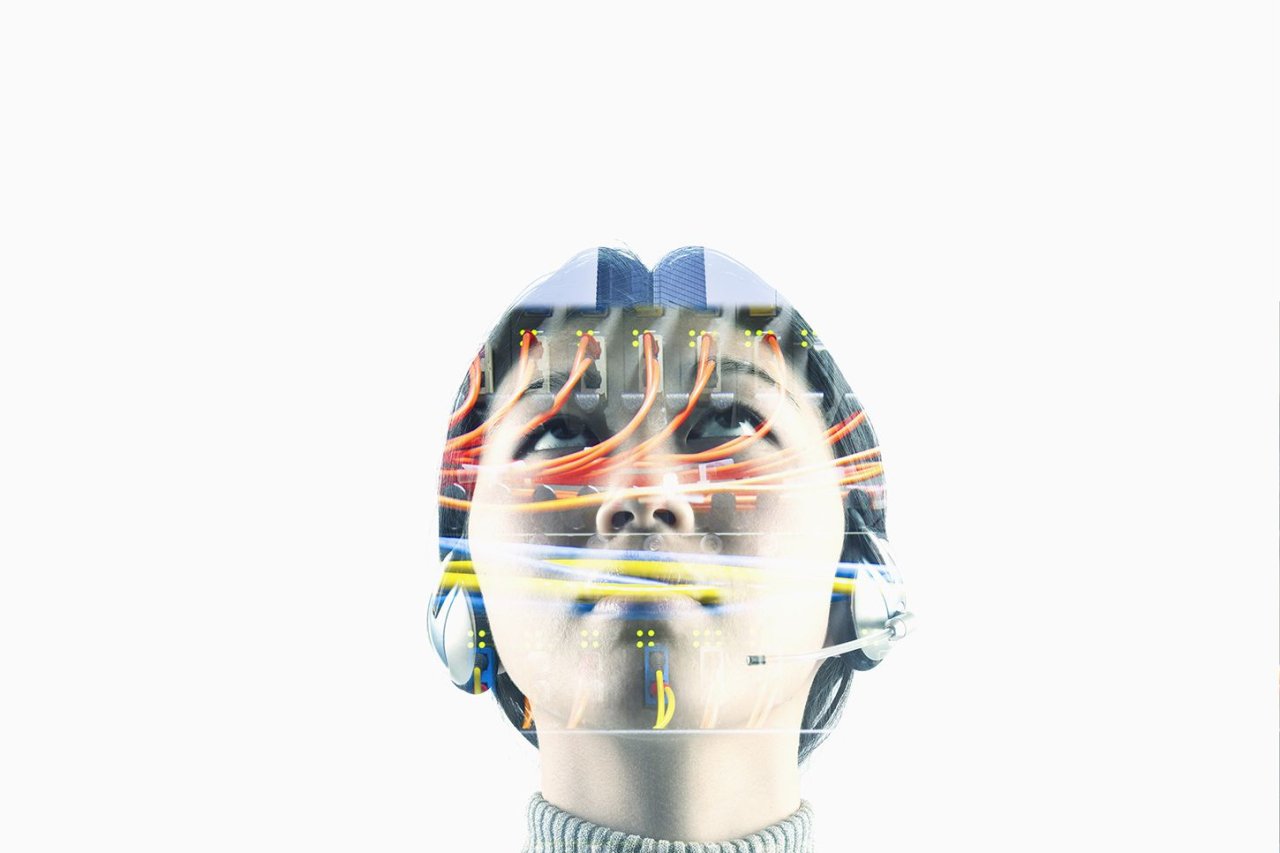

AI will keep getting better and more pervasive. Heck, Elon Musk started a company called Neuralink to make AI chips that we can just embed in our skulls. An Uber driver wouldn't have to use a phone and an app—just plug Waze into his or her brain. Success will go to those who see such advances as an opportunity. If it feels like a threat, you might want to start lobbying the government for protection. Or sign up for TaskRabbit.