The lazy river may seem like the most pleasant of diversions, but it is that rare feature of American life capable of eliciting bipartisan outrage. Those of us who do not enjoy lazy rivers condemn them, especially if their cost figures into the tuition we pay for our children to attend an institution of higher learning. No, the lazy river is not yet a staple of the American college campus. But there was a time when science laboratories on campus were rare, too.

What is a lazy river? Imagine the backwoods of Arkansas, midsummer, bank crowded with cottonwoods, willows bowing to the muddy water, fish are jumping, cotton is high. That is not, in fact, a lazy river. The lazy river is not especially concerned with ecologic detail. Imagine instead an ordinary swimming pool stretched into a sinuous strip. Give it a gentle current. Hand the kids inflatable tubes. You now have a lazy river. As do many—probably too many—American university campuses.

The lazy river has recently become emblematic of what ails higher education, with the requisite New York Times denunciation—"No College Kid Needs a Water Park to Study"—published in early January. It is a symbol of excessive cost and decreasing educational returns on investment. More broadly, the lazy river is a sign of American indolence, of our collective postindustrial lassitude, the nation that once tamed the Mississippi now slumbering poolside, scrolling through Instagram. Our rivers, along with our spirits, no longer surge.

Now comes the inevitable Then again. Complaints that American college students are pampered wasteoids were around long before an Orlando Sentinel columnist said the University of Central Florida's proposed $25 million athletic complex—including, of course, a lazy river—was "a sign of whacked-out times."

Suspicions about the American university are nearly as old as the institution itself, which began with the founding of Harvard in 1636. Benjamin Franklin, who never attended college, visited the campus in 1722. He wasn't impressed. In an editorial published that year, he mocked Harvard as "the Temple of Learning, where, for want of a suitable Genius," students "learn little more than how to carry themselves handsomely, and enter a Room genteely, (which might as well be acquir'd at a Dancing-School,) and from whence they return, after Abundance of Trouble and Charge, as great Blockheads as ever, only more proud and self-conceited." And that was long before the University of Virginia started offering a course about the HBO series Game of Thrones.

Eighteen years after Franklin's letter was published, he started his own institution of higher learning, the University of Pennsylvania, where students would "learn those Things that are likely to be most useful." This mission continued well into the 20th century. "Now it is very much a pretrade school," The Harvard Crimson said in 1956, "while the other Ivies uphold...education for education's own sake," adding rather cruelly that the "Penn undergraduate is not especially concerned with his courses." Ouch.

A decade after that assessment, a wealthy and cocksure scion of Queens, New York, transferred from Fordham University, in the Bronx, to Penn. The school indeed gave Donald Trump a practical advantage, though perhaps not quite in the way Ben Franklin had intended. When Trump ran for president, he frequently spoke of his two years at Wharton as confirmation of what he already knew about himself and needs so desperately to tell others. "I'm, like, a really smart person," he said in the summer of 2015, referencing his time there. He later said Marco Rubio, the Republican senator from Florida, would not have been admitted to Wharton. "Got to be very smart to get into that school, very smart."

But for Trump, intelligence has little to do with educational achievement. He is, like more and more Americans, contemptuous of experts and their expertise. "Professor," writes Michael Wolff in his new book, Fire and Fury, "was one of his bad words, and he was proud of never going to class, never buying a textbook, never taking a note."

That may explain why the educated have consistently been maligned in his administration—experts replaced by businessmen, professors supplanted by billionaires. Many of the men and women in Trump's White House share his dismay about what they see as the devolution of the college education into an extremely expensive series of acquired attitudes. In ways large and small, they are seeking to return that experience to what it was before anyone had heard of safe spaces or affirmative action.

They are abetted in this project by a growing number of Americans appalled by the cost of college and doubtful of its utility. Liberal concerns about college overlap just enough with those of Trump and his supporters to turn what might have been a partisan assault into a broader condemnation of what college has become. Daniel Drezner, a Tufts University scholar who has written about the conservative animus toward higher education, calls it a "war on college" in his Washington Post column. His outlook is pessimistic.

"I would not say," he tells me, "that college is winning."

Instinct Over Intellect

Before the war on college, there was war by college, or at least by many college students. In 1964, Mario Savio, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, effectively launched the era of the college protest by urging students "to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels" of power's "odious" machinery. Bodies upon gears is a bloody enterprise. In 1969, a student was shot and killed at a Berkeley protest. The following year, four students were shot and killed by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State. Almost four months later, a bomb planted by radicals exploded at a University of Wisconsin research center that conducted work for the U.S. military. A researcher was killed.

In 1971, Lewis Powell Jr., then a lawyer in private practice, wrote a letter to an official at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in which he warned that "the assault on the enterprise system is broadly based and consistently pursued." The "Powell Memo" has become famous as both a statement of principle and a declaration of war, the machine's reply to Savio. Powell identified the college campus as "the single most dynamic source" of the growing opposition in America to free-market capitalism. The future Supreme Court justice argued that liberal colleges produced liberal intellectuals who "end up in regulatory agencies or governmental departments with large authority over the business system they do not believe in." The college was, he argued, both feeding corporate America and undermining it.

As Powell was writing those words, liberals sought refuge from the Vietnam War draft in the groves of academe. By the 1980s, they had bloomed into what the conservative writer Roger Kimball called "tenured radicals," safely preaching about the depredations of capitalism from an endowed professorship. At the same time, the Reagan presidency emboldened the rise of a campus conservative movement, its convictions articulated by The Dartmouth Review, founded on the New Hampshire campus in 1980. "A fresh conservative wind is beginning to blow through the campuses of the Ivy League and beyond," The New York Times noted in 1981.

One of the Review's early editors was Dinesh D'Souza, who had come to Dartmouth from India. After graduating, he went to work for President Ronald Reagan as a policy adviser, then joined the conservative American Enterprise Institute. In 1991, he published Illiberal Education, a systematic evisceration of what he saw as the most troubling campus plagues: affirmative action, identity politics, historical revisionism. His conclusion was that the right was losing the battle outlined by Powell in 1971.

Little of what has transpired in the past 25 years has made D'Souza optimistic.

"The university in general has become more one-sided intellectually, philosophically," the conservative pundit told me when we spoke earlier this winter.

Democrats outnumber Republicans among college faculty at a ratio of 11.5-to-1, according to a recent study in Econ Journal Watch, an online journal of economic research. On CNN and MSNBC, college professors from Austin and Palo Alto routinely denounce Trump, and the American Association of University Professors has a website, One Faculty, One Resistance, dedicated to combating the Trump administration and its Republican abettors. Targets include the Texas Legislature—which in 2016 permitted concealed weapons on public university campuses—as well as the administration's aversion to expertise, its favoring of instinct over intellect. The site points to "a campaign of harassment against researchers in politically charged fields such as climate change, and an administration in the White House that is determined to suppress research findings in these areas and to reduce government funding for research." The radicals aren't just tenured; they're now organized.

Trump's supporters aren't likely to have much sympathy for the harassed professoriate. Last summer, a poll by the Pew Research Center found that 58 percent of "Republicans say colleges and universities are having a negative effect on the way things are going in the country." College-educated voters used to identify with the GOP: Reagan won 61 percent of the college-educated electorate in 1984. Today, the educated vote for Democrats, while the rampant liberalism on campus provides Republicans with a perfect foil.

"Conservatives," D'Souza says, "are up in arms."

Charlie Kirk is probably D'Souza's most capable understudy in the campus wars. He is the founder of Turning Point USA, a conservative advocacy group that wants to "build the most organized, active and powerful conservative grassroots activist network on college campuses across the country." It already has branches on more than 350 campuses.

Kirk never graduated college. In high school, he'd wanted to attend West Point, but that didn't work out: He has said that he believes his slot at the prestigious military academy was given to a less-qualified minority applicant. Having enjoyed a summer volunteering on a senatorial campaign, he decided to skip college and work full time in politics. Turning Point USA, the group he founded, enlists students to challenge the very institutions they attend. "We're just fighting for the ideas of free speech," Kirk tells me. A couple of weeks after the 2016 presidential election, Turning Point USA began to publish Professor Watchlist, a website whose mission is to "expose and document college professors who discriminate against conservative students and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom." The reviews from the mainstream media were unkind: "grotesque" (Slate); "a sign of the right's new McCarthyism" (Salon).

Conservatives like Kirk believe the McCarthyism is being practiced by the left. He wants to promote a "culture of true intellectual diversity," in which unpopular speech is countered by more speech, not by protesters shouting down guest speakers. He is convinced most members of his generation are not radicals, but that the radicals have been allowed to run college campuses as their own fiefdoms, where undocumented immigrants are protected and everyone composts. "There's this growing base of conservative-minded students," he says. They intend, with the help of the current administration, to force the American college to retreat from the liberalism of the last half-century.

Social Justice Warriors With Hunting Licenses

It was late February 2016, and Trump had just won the Republican presidential primary caucus in Nevada. Now, he was at a victory rally, rapturously discussing the exit polls, rattling off the various demographics he'd won. "I love the poorly educated," he declared. Though he also praised his supporters for their intelligence, only his fondness for "the poorly educated" became a YouTube sensation. That's because it confirmed what many plainly saw in the numbers, which was that Trump's support came in good part from working-class voters. Because they were aggrieved, some said. Easily duped, others claimed.

Analyzing voting patterns in the presidential election, pollster Nate Silver published an article on his site, FiveThirtyEight, titled "Education, Not Income, Predicted Who Would Vote for Trump." Trump loved the poorly educated, and the poorly educated loved him right back. The well-educated, on the other hand, loathed him. Dartmouth, that onetime conservative redoubt, had a student body where support for Trump just days before the election stood at 4.8 percent. About 90 percent of the campaign contributions by Harvard faculty members went to Hillary Clinton.

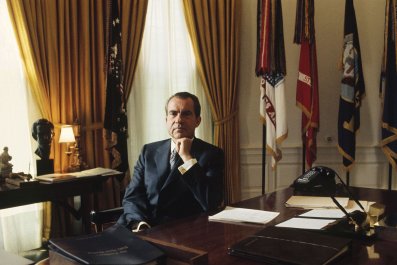

In the Oval Office, directly above Trump's left shoulder, hangs a portrait of President Andrew Jackson, who "confronted and defied an arrogant elite," as Trump said adoringly last spring. Born to poor Irish immigrants, Jackson had only a grade school education. He is one of nine presidents who did not attend college. The composition of Trump's Cabinet suggests that his disdain for intellectuals was more than just campaign-trail bluster. It is stocked with billionaire executives and decorated generals, men (for the most part) who rose through the ranks of enormous organizations by following orders and capably executing them.

Whether they are following orders or personal ideology, his Cabinet members seem to have eagerly joined the battle against academe. However, toppling higher education—or reforming it, if you like—is difficult for this administration because there isn't a single, all-encompassing entity to confront. The nation's 4,724 degree-granting institutions are attended by 20.2 million students. The Department of Education has nominal oversight, though little actual power. Trump's advance on higher education has consequently been piecemeal, more guerilla warfare than frontal assault.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions has decided to wage the ideological battle articulated by activists like D'Souza and Kirk. Last summer, his Department of Justice announced it would begin "investigations and possible litigation related to intentional race-based discrimination in college and university admissions," likely related to a suit by Asian-Americans who allege that they were not admitted to Harvard because affirmative action favored African-American and Latino students.

Trump's education secretary, Betsy DeVos, has sought to dismantle what the Obama administration did to make college more affordable and welcoming. A conservative Christian from Michigan, DeVos has taken to this task with quiet efficiency. In 2011, President Barack Obama's Department of Education directed all universities receiving federal funds to comply with Title IX—which covers sex discrimination—or face investigation. Three hundred and forty-four investigations were launched in the six years that followed. Conservatives complained that the directive unleashed witch hunts, with due process forsaken. But some outside the right also found the Title IX investigations excessive. The writer Laura Kipnis, for example, denounced this new campus feminism that "prefers to imagine women as helpless children."

DeVos appointed Candice Jackson to head the Office of Civil Rights. Jackson is a Christian conservative who, as an undergraduate, wrote for The Stanford Review, a younger sibling of The Dartmouth Review founded by future billionaire Peter Thiel. In September, when the Department of Education canceled the 2011 directive on Title IX, this was a victory for conservatives: "Marginally educated social justice warriors were given a hunting license to pursue male students and harry them from campus on the flimsiest of evidence," one blogger wrote.

At the same time, the administration's general affinity for deregulation—evident across all aspects of the federal government—has done little to help those "forgotten Americans" largely responsible for Trump being president. DeVos appointed Robert Eitel, for example, as her senior counsel. Eitel worked for the for-profit education company Bridgepoint Education, which the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found "deceived its students into taking out loans that cost more than advertised." Several months after Eitel's appointment, the Associated Press reported that DeVos was "considering only partially forgiving federal loans for students defrauded by for-profit-colleges."

For-profit colleges had been a particular target of the previous administration, which saw them as mercenary outfits. Under Obama, for-profit colleges had to show they were helping students attain "gainful employment." The gainful employment rule has been scrapped, along with the one regarding loan forgiveness.

DeVos's nominee for the department's general counsel, Carlos Muñiz, consulted as a private lawyer in Florida for Career Education Corp., a for-profit outfit. "DeVos Embrace of Predatory For-Profit Colleges Is Breathtaking," said a HuffPost article, citing appointments like Muñiz and the rollback of Obama-era regulatory measures.

During the Democratic presidential primary, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders frequently discussed the notion of tuition-free public universities. It was an idea enthusiastically supported by the left. DeVos was pithily skeptical when Sanders asked her about that proposal during her nomination hearing.

"There's nothing in life that's truly free," said the billionaire heiress.

Killing Piggy

Students across the nation protested on the day of Trump's inauguration. Kumars Salehi, a Palestinian activist who is a doctoral student in the German department at Berkeley, tweeted out a photo of empty student desks, adding, "Every classroom should look like this today."

What the protesters didn't seem to grasp was that they were confirming, with devastating precision, the conservative critique of higher education. One letter-writer to a newspaper in upstate New York called college students "little prima donnas," comparing them unfavorably with members of the military. "They didn't get their way in the last election. Their only known reaction is acting out (you know, being a little brat)."

Less than two weeks after Trump was inaugurated, the University of California, Berkeley, prepared to receive the right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos on campus. His "Dangerous Faggot" national speaking tour, little more than orchestrated provocation, might have been ignored during the Obama years, but now the man Yiannopoulos called "daddy" was president. The night of the inauguration, a protester was shot before a Yiannopoulos talk at the University of Washington. Yiannopoulos reveled in this chaos; the chaos was by far the most compelling aspect of his tour.

By this measure, the Berkeley visit was his pièce de résistance. Black-clad protesters descended on Sproul Plaza, the central square on campus where the Free Speech Movement began in 1964. They taunted cops, set off flares and set a light tower on fire. Windows were broken. The talk was canceled, but the crowd stayed, high on victory. After being expelled from Sproul, they marched through downtown Berkeley, destroying bank outlets and trashing a Starbucks.

The following morning, the world woke up to a tweet from Trump: "If U.C. Berkeley does not allow free speech and practices violence on innocent people with a different point of view - NO FEDERAL FUNDS?" Yiannopoulos, chased off campus, vowed to return, explaining, "That is the price you pay for being a libertarian or a conservative on American college campuses."

But it wasn't just Berkeley. In the months after the February 1 violence, campuses exploded. Working-class whites yearned for America the way it was; the increasingly nonwhite college students imagined America as it had never been.

The difference was not just ideologic but demographic. Trump's base—older, whiter and more male than the general population—was becoming the obverse of the collective student body of the American college campus, which is now majority female (55 percent, according to 2014 estimates), increasingly nonwhite (whites composed 86 percent of all college students in 1976; by 2014, they had only 58 percent of the share) and often from other countries (international students were 1.7 percent of the college population in 1970 but 4.8 percent in 2015, for a total of 945,000 students). The former represents the America that was; the latter, the America that will be.

Just like Trump supporters, college students expressed their dissatisfaction with large, mediagenic rallies. Like those raucous Trump rallies during his campaign, they were a place to loudly express grievances to those who already shared them—but also to the journalists recording the event. It may be uncomfortable to admit, but #MakeAmericaGreatAgain and #BlackLivesMatter were about what America had promised, and how America had come up short.

The Berkeley riots in February ushered in a year of protests:

- About two weeks later, students at Cornell University in upstate New York protested a planned talk by Michael Johns, a former speechwriter for George H.W. Bush, calling the event a "safe space for white supremacy."

- On March 2, students at Middlebury College, in Vermont, disrupted a talk by conservative thinker Charles Murray. As he was leaving the lecture, Murray and school officials were "physically and violently confronted by a group of protesters," a Middlebury spokesperson told the Addison County Independent, a local newspaper. A professor was injured in the scuffle. She later called the assault "the saddest day of my life" in a Facebook post.

- A month later, pro-police advocate Heather MacDonald of the Manhattan Institute was slated to speak at Claremont McKenna College, outside of Los Angeles. Protesting students "accused her of 'neglecting the state-sponsored genocide committed against black people' and said she represented 'white supremacist and fascist ideologies,'" according to The Washington Post. MacDonald's talk was canceled.

- A petition by a student at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, sought the cancellation of an honorary degree for PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi. It began with a description of a Pepsi advertisement that seemed to tie Pepsi to the Black Lives Matter movement. The petition also said Nooyi was "complicit in the current administration's racist, xenophobic, misogynistic, and anti-environment agenda" because she sat on one of Trump's corporate councils. Nooyi received her honorary degree.

- Last fall, students at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, protested "white supremacy" on campus. The target of their outrage was a humanities professor who had shown his class an old Saturday Night Live sketch in which comedian Steve Martin had played an Egyptian pharaoh. The racial and cultural implications of the skit had subsequently been discussed, but protesters nevertheless felt that showing the skit in class was racist.

Maybe the coverage of all this was exaggerated, inflated by conservative scolds like Tucker Carlson of Fox News, his mouth tightening as he played his latest "College Craziness" clip. At the same time, the evidence was clear and couldn't be dismissed as fake news. Even liberals started to worry.

Especially troubling to many was the demonization of a liberal professor at the exceedingly liberal Evergreen State College in Washington state. The professor, Bret Weinstein, had objected to students of color calling for a day without whites on campus. This temporary purge was deemed necessary, Weinstein later wrote, because those students were "feeling as if they are unwelcome on campus, following the 2016 election." For his refusal to comply, Weinstein was accosted by students who called him a racist and white supremacist. He resigned from the college, which paid him a $500,000 settlement. But the incident, which made national headlines, suggested to some that the quest for social justice had lapsed into a Lord of the Flies nightmare.

"Let's face it," says Tufts University's Drezner. "We're a ripe target."

New School for Fools

Adam Carolla, a comedian and conservative activist, thinks college is a felonious waste of time. A native of Los Angeles, he attended a local community college, where, he says proudly, he learned little to nothing. He found working as a carpenter far more instructive. "Everything you need to know in life is in building a house," he tells me.

For the last year, Carolla has been working with right-wing radio host Dennis Prager on No Safe Spaces, a documentary that promises to serve up "trigger warnings, real social justice warriors, and maybe even some tailgating," as well as an exposé of "very bad ideas [that] have ruined college for young people and now threaten to ruin the country by creating a nation of precious snowflakes who melt when they encounter an idea that they disagree with." Carolla and Prager have raised more than $638,500 through crowdfunding, easily exceeding their original goal.

When I spoke to Carolla, however, he was less concerned about safe spaces than a more basic question: What is college good for? Like many on the left, Carolla recognizes that colleges—even fairly average ones, let alone the bastions of prestige—have become obscenely expensive, with tuition at private colleges having risen from $9,500 in 1980 to $34,740 at the beginning of this year. Public universities have seen a similar increase. At the same time, a PayScale study on recent college graduates reached a dispiriting conclusion: "Millennials are not adequately prepared for the workforce." They are paying more than ever, but getting little in return. The recent protests on campus only underscore, for some, the frivolity of a college education: Does it really make sense to pay $50,000 a year to debate whether The Sopranos engaged in cultural appropriation?

Carolla argues that digital innovation could democratize college, allowing students to learn what they'd like without leaving their laptops (or augmented reality sets, as the case may soon be). "I don't believe that education is something that needs to take place on a designated plot of land called 'college,'" he says.

Critiques like Carolla's have also been voiced on the left. There was, for example, The End of College: Creating the Future of Learning and the University of Everywhere, by Kevin Carey, the New America Foundation's education policy scholar. For evidence of higher education's skewed imperatives, he points to George Washington University, where a concerted campaign called the Absolut Rolex Plan turned this former commuter school in Foggy Bottom into "a magnet for the children of new money who didn't quite have the SATs or family connections required for admission to Stanford or Yale." The school climbed in college rankings, but that was a triumph of marketing, not education.

Elsewhere, Carey writes that online coursework will effectively replace the kind of college we've been attending since the founding of Cambridge 800 years ago. "The next generation of students will not waste their teenage years jostling for spots in a tiny number of elitist schools," Carey writes. Note the use of elitist instead of elite. As the prestige of attending college has increased, the utility of having graduated from college has diminished. This is a paradox, a rather ugly one.

Thiel, co-founder of The Stanford Review, went on to help start a somewhat more profitable enterprise: PayPal. That made him a billionaire, as did his prescient investment in Facebook. Two decades in Silicon Valley have also convinced him that college is an increasingly moribund rite of passage. "A lot of graduates can't get good jobs; they're saddled with debt and moving back home with their parents. People are starting to see that something has gone wrong," he says. Thiel now offers a $100,000 fellowship to any intrepid student willing to drop out of college and "build new things instead of sitting in a classroom." In his own way, Thiel is also looking for a few good carpenters.

Liberalism and Lassitude

Public universities have it even harder than private ones, since their fortunes are dependent on elected officials. The same election that elevated Trump also saw Republicans score victories in gubernatorial races and state legislatures, as they had been doing since the 2010 election fueled by the Tea Party movement. The GOP now has 26 "trifecta" states, with Republicans there controlling both legislative chambers and the governor's mansion. Democrats have just seven trifecta states.

"Defunding public education has been a huge project of the right," says William Deresiewicz, who was exceptionally critical of higher education in his 2015 book, Excellent Sheep. He believes that may be partly out of conservative dogma about "fiscal prudence," but it's also a "long-standing antipathy to educated elites," especially ones whose tenure comes at taxpayers' expense.

Despite the Ivy League's outsized place in the popular imagination, only 16 percent of American university students attend a private institution of any kind. The eight Ivies represent .04 percent of the nation's collective undergraduate body. The vast majority attend a public institution funded in large part by the states. Some, like Berkeley, can also depend on lavish federal or private grants, the donations of wealthy alumni and out-of-state (and out-of-country) tuition. But smaller colleges cannot. And even the largest, most prestigious state systems—those of California, Wisconsin and North Carolina—could suffer at the hands of Republican lawmakers. Some already have.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison is emblematic of the complex mixture of admiration and resentment a flagship public university engenders. In the early 20th century, the University of Wisconsin became associated with the state's progressive leaders, who declared that the purpose of an education was not to do well but to do good. In 1905, University of Wisconsin President Charles Van Hise articulated what would come to be known as the Wisconsin Idea: "I shall never be content until the beneficent influence of the University reaches every family of the state."

Some saw this as overreach that aligned far too neatly with progressive political aims. "Many graduates are leaving with ideas that are un-American," complained Emanuel Philipp, a conservative running for governor.

In 2010, Wisconsin elected Scott Walker as its governor. A student of the libertarian Koch Brothers and, to critics, an all-too-eager product of their Americans for Prosperity political machine, Walker sought to undo the New Deal safety net that had, for decades, been the target of billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch. He began with the public university, that nexus of liberalism and indolence.

Some of the changes were cosmetic but significant, as when he sought to remove from the university system's mission statement two sentences—the crux of the Wisconsin Idea. They said the University of Wisconsin was "designed to educate people and improve the human condition. Basic to every purpose of the system is the search for truth." There were more substantive moves too. Walker cut the school's budget by $250 million, which led to hundreds of job cuts and scaled-back programs. After he moved to reduce tenure protections for professors, one of them compared Walker to Hitler.

Wisconsin is only the most egregious example of this trend, in which Republican governors cut spending on higher education in the name of fiscal prudence. Louisiana has reduced its spending on state colleges by $700 million over the past decade; Kansas, which became a kind of Dr. Frankenstein laboratory for Koch-style libertarianism under Governor Sam Brownback, clawed back $30 million from that state's public universities in 2016.

Overall, the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities found, spending on higher education dropped by $9 billion from 2008 to 2017. "As states have slashed higher education funding, the price of attending public colleges has risen significantly faster than what families can afford," that report found.

"I don't think this has anything to do with fiscal prudence whatsoever," says Tufts's Drezner, pointing to college sports as proof. In many of the states where public education spending has been drastically scaled back, college athletics continue to benefit from politicians' largesse. In 39 states, including many led by supposedly spendthrift Republicans, the best-paid public employee is a college-level football or men's basketball coach. Nick Saban, the University of Alabama football coach, makes $11 million a year in salary. The average professor at the same university earns about 1/100th of that.

Fat, Drunk and Stupid

Like the steel factory and the prim suburb, the college campus occupies a dear place in the American imagination. Because of the postwar baby boom, that image is largely informed by midcentury tropes. Yes, there are now more women and minorities, as well as engineering students from Albania. Despite that, the college of collective fantasy is Animal House: a bunch of guys who are fundamentally good but are, for the time being, up to no good.

But as the film's primary antagonist, the joyless Dean Wormer, warns the fun-loving outcasts, fat, drunk and stupid is no way to be. And the American college has come to embrace that toxic triumvirate, plagued by administrative bloat, divorced from the intellectual demands it once espoused. We have all become Bluto Blutarsky—the film's titular animal—swigging bourbon straight from the bottle, then heading out for a nap on the lazy river.

Trump intuitively grasps that something is amiss with college education, but he has delegated the hard corrective work to Cabinet members—Sessions, DeVos—without articulating a vision for the American university. They may dismantle Obama's legacy on higher education, but it isn't clear if they intend to erect a framework of their own.

"It's not a new project, to try to cut the university down to size," says Christopher Newfield, a scholar of higher education at the University of California, Santa Barbara, speaking in particular of conservatives' long-standing intentions. At the same time, never have criticisms of higher education found so much traction among so many.

"Every part of it," Newfield tells me in what amounts to a confession, "is not working the way it's supposed to."