There was a brief moment in mid-November when education reformers were thrilled about President-elect Donald Trump's swamp-draining imperative and what it might mean for the nation's eternally beleaguered public schools. On November 16, Trump met at his Manhattan tower with Eva Moskowitz, whose Success Academy charter network has achieved impressive results with children of color across New York City. The following weekend, he entertained Michelle Rhee, the former head of Washington, D.C.'s public schools, at his golf club in New Jersey. Despite her uneven results, Rhee remains popular with those who think incompetent teachers and the unions that protect them are holding back America's kids.

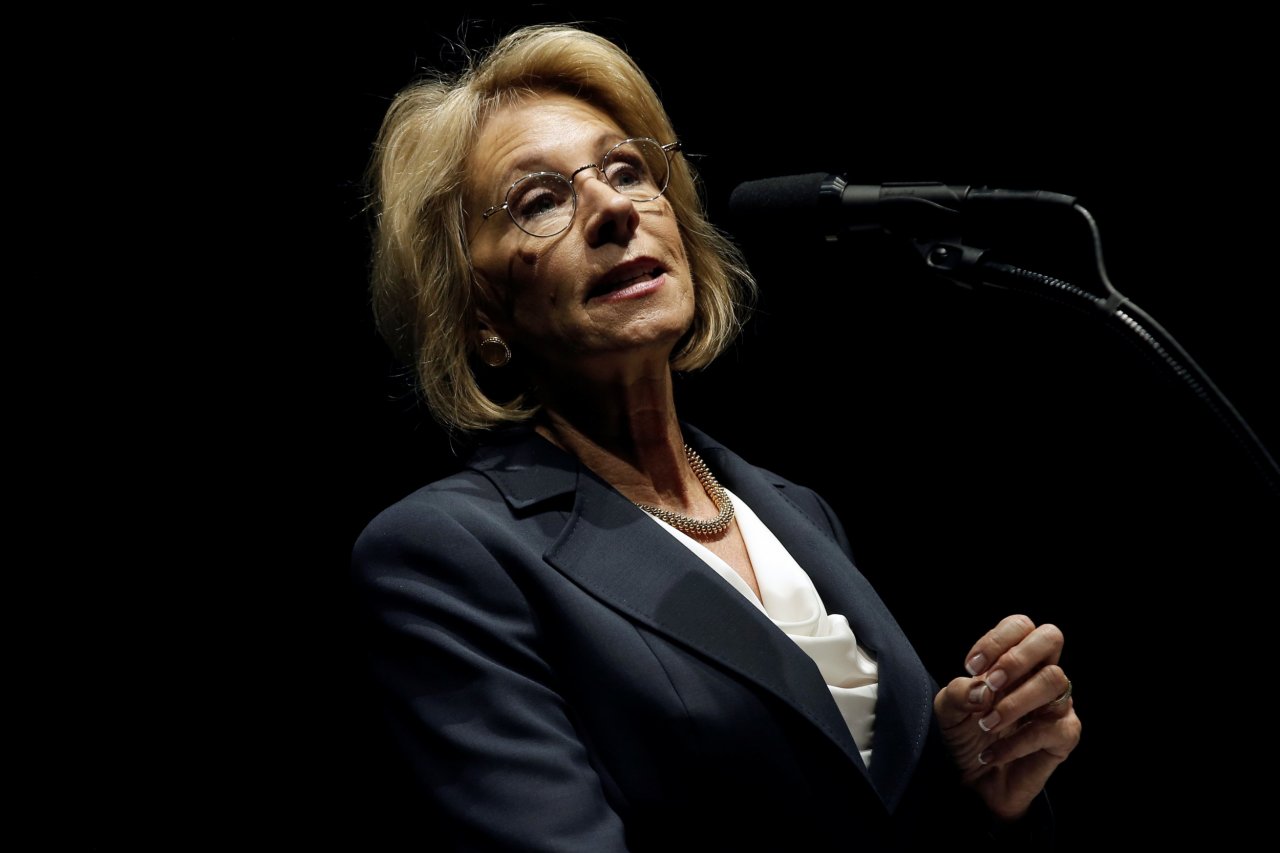

Instead, Trump chose Betsy DeVos to head the Education Department, a federal agency with oversight over all of the nation's educational institutions, from prekindergarten programs to graduate schools of business. The choice mystified all those who'd figured Trump was looking for a capable, forward-looking technocrat focused on student testing and teacher accountability. The choice horrified teachers unions, as DeVos is a billionaire Republican who has worked assiduously to weaken the public schools in Michigan.

Comedian Rob Delaney tweeted, "Trump's pick of DeVos as Sec. of Education is more hateful than pouring a vat of shit out of a helicopter onto a group of 1st graders." Crude as that sentiment may be, it reflects the prevalent perception—unfair, perhaps—that DeVos is unsuited to her post, having never worked in a school or a school district. Her nomination is in keeping with Trump's apparent conviction that nothing fuels government work better than antipathy to the government.

DeVos would not be the first ideologue to head the Education Department: William Bennett, appointed by Ronald Reagan, was a conservative culture warrior of the first order. George H.W. Bush's appointments, Rod Paige and Margaret Spellings, were also no liberals. But ever since the first education secretary—Shirley Hufstedler, appointed by Jimmy Carter to the new post in 1979—nearly every person to hold that office has had direct experience in teaching or educational administration (two were governors who'd enacted large reform measures).

DeVos, by contrast, is a professional lobbyist. She may be qualified, but when it comes to the battlefields of public education, she is plainly inexperienced.

'Christ's Agent of Renewal'

Grand Rapids, Michigan, has largely defined the life of the woman born in 1958 as Elisabeth Prince. She grew up in nearby Holland, on the shores of Lake Michigan, where her father, Edgar Prince, ran an auto parts empire that he would eventually sell for $1.35 billion. The family belonged to the Reformed Church in America, which has its roots in a kind of Protestantism known as Calvinism, the predominant faith of the Dutch who settled western Michigan.

Some flee home for college; Betsy Prince traveled just 30 miles to Grand Rapids, where in 1975 she enrolled in Calvin College, from which her mother, Elsa, had graduated. Any attempt to forecast what DeVos might do as the nation's education secretary must begin here, at this college of 4,000 that bids its students to act as "Christ's agents of renewal in the world." The college is affiliated with the Christian Reformed Church and takes its religious mission seriously: Faculty members, for example, are required to send their own children to a Christian secondary school.

The college is named after John Calvin, the 16th-century French thinker from whom Calvinism gets its name. A branch of Protestantism that took root in Northern Europe, Calvinism hews to its founder's doctrine of predestination, which holds that God has predestined all sinners to Hell, and while he chooses to save some as an act of grace, that salvation cannot be earned. No amount of effort is sufficient to rescue the damned from damnation. It is also among the more intellectual of the various Protestant movements. "Calvinists are usually smart," says Julie Ingersoll, a scholar at the University of North Florida who has studied conservative Christianity. "The core of worship will be a sermon that is sophisticated and philosophically inclined."

Kenneth Pomykala attended Calvin College at the same time as Prince and remembers her "vaguely." Today the head of Calvin's religion department, Pomykala estimates that back then, perhaps 90 percent of the students belonged to the Christian Reformed tradition. "One of the things Calvinism is known for is that one's religious values should affect the way you live all of life," Pomykala says. "It doesn't make the separation between private religion and public life."

At Calvin College, Prince studied business economics and served on the student senate; she volunteered on Gerald Ford's losing presidential bid in 1976 and worked for other Republican campaigns. In 1980, she married Dick DeVos, a native of Grand Rapids and a student at nearby Northwood University who stood to become the heir to the Amway fortune, the massive marketing company co-founded by his father that some have called a pyramid scheme. His family, like hers, was conservative, pious and very rich.

The Voucher Queen

The DeVoses have four children, whom they raised in Ada, a wealthy suburb of Grand Rapids, where the annual median household income today is almost $122,000, more than double Michigan's average of about $49,000. The town, the seventh wealthiest in Michigan, has unsurprisingly good public schools, but the DeVos children apparently did not attend them. Two daughters were at least partly home-schooled, a fact that has been happily noted by home-schooling advocates, many of whom are religious conservatives elated to finally have a booster in Washington, D.C. Both sons attended the Grand Rapids Christian High School, which has a DeVos Center for Arts and Worship.

Though she has been reticent with the press since her nomination to the Trump Cabinet, DeVos was not shy about expressing her convictions previously. In 2013, she told Philanthropy magazine that her desire to improve education began with a visit to the Potter's House Christian School in Grand Rapids, a private religious academy. "At the time, we had children who were school-age themselves. Well, that touched home. Dick and I became increasingly committed to helping other parents—parents from low-income families in particular. If we could choose the right school for our kids, it only seemed fair that they could do the same for theirs."

The DeVoses began their prolonged assault on Michigan's public education system in earnest in 1990, when Dick DeVos won election to the state's school board. Three years later, the couple led a successful push for legislation that would welcome charter schools to Michigan (the first charter school in the nation had opened in 1992 in St. Paul, Minnesota). But while charter schools bloomed there, they didn't thrive. As early as 1997, the state auditor found the state has shown "limited effectiveness and efficiency in monitoring" charters. Two years later, the Michigan Department of Education worried there was "no defined system of quality control in regard to charter schools," despite there being 138 institutions that enrolled 30,000 students across the state.

The DeVoses persisted in advocating for more choice, disregarding calls for oversight. In 2000, they pushed for Michigan to adapt a voucher system, which proposed to give students about $3,300 to attend a private school of their choice, including a religious one. The Wall Street Journal wrote, "By focusing on the worst-of-the-worst schools, the campaign also has helped recast the image of vouchers from a middle-class pipe dream to a lifeline for inner-city kids. And in the long, heated, name-calling, lawsuit-filing history of school vouchers, that combination eventually may prove tough to beat."

The voucher measure failed to pass, but DeVos, who'd headed the Michigan Republican Party for the latter half of the 1990s, redoubled her efforts. She began to establish groups like the Great Lakes Education Project (GLEP), founded in 2001. The group's goal is "supporting quality choices in public education for all Michigan students," in part by shaming public education. For example, one ad campaign, called Got Literacy?, featured misspelled school signs: Welcome Back, Hope You Hade a Good Break; 15 best things about our pubic schools. The campaign didn't mention that the first sign was from Arizona, and a student joke besides, while the second was made for an Indiana school by an ad agency.

Supporters of DeVos argue that Michigan's schools were dismal and that her only mission has been to provide a life raft to those stuck on a sinking ship. Matt Frendewey, communications director at the American Federation for Children (AFC), another group DeVos founded, calls her a "relentless advocate for students," particularly poor children of color. School choice, he argues, is the first and necessary step to better educational outcomes.

In 2011, GLEP and its conservative allies won a major victory when the Michigan Legislature erased the charter school cap, creating what is effectively an unrestrained market for charter school operators. DeVos scored another victory last summer, when she and her husband spent $1.45 million to stymie a legislative effort to provide more oversight to Michigan's charter schools.

"If I wanted to start a school next year, all I'd need to do is get the money, draw up a plan and meet a few perfunctory requirements," wrote a dismayed Stephen Henderson, the editorial page editor of the Detroit Free Press. "I'd then be allowed to operate that school, at a profit if I liked, without, practically speaking, any accountability for results. As long as I met the minimal state code and inspection requirements, I could run an awful school, no better than the public alternatives, almost indefinitely."

It's unclear how closely DeVos looked at the achievements of the charter schools that sprouted in Michigan because of her efforts. Did she know that many of them were failing? And if she knew, why did she do nothing?

Detroit Flunks

The best argument against Betsy DeVos can be made with a single word: Detroit. On the National Assessment of Educational Progress, Michigan's biggest city has the worst math and reading scores of any large city in America. Its fourth-graders score a 36 on math, while their counterparts in Charlotte, North Carolina, score an 87. Its eighth-graders got a 44 on reading, lagging behind Miami by 33 points.

DeVos claimed that her emphasis on school choice was going to help poor, minority children escape from underperforming public schools. So how did that escape route become a quagmire?

Kids may suffer from a lack of choice, but they can also suffer from an excess of competition. Reporting on the state of charter schools in Detroit last summer, education reporter Kate Zernike of The New York Times described a system that was as at least as chaotic and unproductive as what it supplanted. "While the idea was to foster academic competition, the unchecked growth of charters has created a glut of schools competing for some of the nation's poorest students," Zernike wrote, "enticing them to enroll with cash bonuses, laptops, raffle tickets for iPads and bicycles. Leaders of charter and traditional schools alike say they are being cannibalized, fighting so hard over students and the limited public dollars that follow them that no one thrives."

Douglas Harris, a professor of economics at Tulane University, considers himself a proponent of sensible reform, yet the kind of reform enacted by DeVos in Michigan, he has concluded, is a disaster. In a widely circulated op-ed for The New York Times, Harris wrote that DeVos "devised Detroit's system to run like the Wild West. It's hardly a surprise that the system, which has almost no oversight, has failed. Schools there can do poorly and still continue to enroll students."

Harris contrasted Detroit with New Orleans, where the school system is saturated with charters. Those charters are successful because they're expected to meet the same high standards that educators demand from students. Lax oversight of a school district is unlikely to produce much better results than lax oversight of a classroom.

"The DeVos nomination," Harris wrote, "is a triumph of ideology over evidence."

Much of the fault for the panoply of bad choices in Detroit can be placed on for-profit charters, according to Samuel Abrams, a scholar of privatization in education at Teachers College at Columbia University in New York and the author of Education and the Commercial Mindset. Whereas about 10 percent of charters nationwide are for-profit, about 80 percent of charters in Michigan mix profit-making with teaching. "The fundamental problem with for-profit school management is that we don't have sufficient transparency for proper contract enforcement because the immediate consumer is a child," Abrams tells me. "He or she is not sufficiently informed to know if a class is being properly taught.

"There is room for cutting corners in the name of profits," Abrams says. "You don't have that in public school."

'Advancing God's Kingdom'

A lot of the worries about DeVos come from association—and insinuation. Some are concerned about her stance on gay rights. She and her husband "have spent heavily in opposition to same-sex-marriage laws in several states," according to Jane Mayer of The New Yorker. Elsa Prince, Betsy's mother, has frequently given to right-wing groups like Focus on the Family and the Family Research Council.

At the same time, it's worth noting that, as the head of the Michigan GOP, she forcefully defended a gay Republican politician who'd been harassed for his stance on a gay marriage amendment. In 2014, she lambasted Dave Agema, a Republican, for making denigrating comments about gays and Muslims. "I couldn't stand by and hold my tongue," she said. And despite her appointment by Trump, she was among those Republicans who bore no love for the candidate, calling him an "interloper" from whom she predicted Republicans would defect. (The DeVoses supported former Florida Governor Jeb Bush and, after he dropped out, Florida Senator Marco Rubio.)

"If you look at Betsy's full record, you won't be able to fit her in a box that some of those who oppose her nomination are trying to put her into," says the AFC's Frendewey. The Windquest Group, an investment group run by the DeVoses, supports clean energy, technological innovation and a well-regarded aviation high school, as well as an arts prize. They were also funders of an arts management institute at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. (The institute has since moved to the University of Maryland.)

Despite all that, detractors have plenty of evidence for their fears. They point, for example, to a recording, obtained by Politico, in which DeVos talks about "advancing God's kingdom" through public education. That only stokes fears that DeVos is a Christian soldier disguised as a public servant.

Ingersoll, the University of North Florida scholar, says that "it's a long-standing goal of the religious right to dismantle public education" and that religious conservatives like DeVos "don't see public schools as religiously neutral." If an education is not Christian, then it is anti-Christian. This is a view, she suggests, DeVos shares with Mike Pence, the religiously conservative vice president-elect, who is expected by some to have Dick Cheney-level influence in the Trump administration.

When I conveyed these concerns to Frendewey, he laughed. "In no way is this some sort of religion-based agenda," he says. Betsy DeVos, he assured me, wants successful students, not "disciples."

Poor Choice for the Poor

Nobody accused Trump's presidential campaign of a wonkish occupation with policy details. Nevertheless, he has been clear about his primary mission in education, which is to inject $20 billion into school choice programs. "As your president, I will be the nation's biggest cheerleader for school choice," he said during the campaign.

As with many other aspects of the Trump platform, there are few details to debate. Abrams, the Teachers College scholar, called the education plan "mystifying," echoing the confusion I encountered whenever I asked, while reporting this story, how Trump and DeVos planned to make school choice a bigger priority.

Tulane University's Harris says that a Capitol Hill controlled by Republicans could pass a tax credit program that incentivizes private education, including religious and virtual schools. But this would probably benefit middle- and upper-middle class families already disposed (and able) to pay for a private education.

The same goes for vouchers. While $20 billion for school choice programs sounds like a large number, there are 15 million children living in poverty in the United States, and the average private school tuition is $9,500. Giving them all a meaningful voucher would require about $142.5 billion, or seven times the amount proposed by Trump for his school choice plan.

Consider, also, that some states that have vouchers, like Ohio and North Carolina, allocate less than $5,000 per student, meaning that families would still have to pay several thousand dollars to send a child to private school if this were in fact part of the Trump reform package. That shortfall notwithstanding, even a $5,000 voucher for every child living in poverty nationwide would cost $75 billion. Much like the border wall with Mexico, the golden-ticket voucher might be an empty campaign promise.

Yet almost certainly, Trump will use federal dollars to reward states for enacting his preferred reforms. That was what President Barack Obama did with Race to the Top, which incentivized data collection, student assessment and better teaching.

Harris says school choice is first on DeVos's agenda. "It's really her only issue."

An Existential Threat

Teachers unions and their liberal allies are alarmed by the DeVos pick. Most charters and parochials aren't unionized, meaning that school choice enervates public sector unions, another favorite Republican goal. "She is an existential threat to public education," says Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers.

When I relayed that quote to Frendewey, he dismissed the worry by noting the many times Weingarten had used tough language about centrist Obama appointees. "They weren't happy with Duncan, they weren't happy with King," Frendewey says, alluding to Arne Duncan and John King, both Democratic education secretaries who met with resistance from teachers unions on matters of student and teacher evaluation. Frendewey and other DeVos associates acknowledge that Detroit schools are a disaster, but it's a fair question whether the failure of that experiment should disqualify her from a federal position.

Yet for conservatives, DeVos's antipathy to traditional public schools is in keeping with a broader desire to lessen what they deem bureaucratic bloat. In an op-ed for The Washington Post, former Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney, whose father George was the governor of Michigan, branded DeVos an iconoclast of the sort demanded by our moribund schools. "The decades of applying the same old bromides must come to an end," he wrote. "The education establishment and its defenders will understandably squeal, but the interests of our children must finally prevail." Romney's voice on this issue matters because he was a frequent critic of Trump throughout the presidential campaign. Moreover, as he notes, the state he once governed, Massachusetts, has the nation's best schools.

The vast gap between the vaunted Massachusetts "education miracle" and the state of Detroit's schools suggests, at least to skeptics, that Romney's confidence in DeVos may be grievously misplaced. And while it is true that Weingarten—my onetime union leader in New York City—has frequently been tough on Democrats deemed insufficiently loyal to teachers unions, her mood when we spoke in early December seemed to me closer to visceral fear than intellectual disagreement. Calling DeVos an "ideological zealot for private education," Weingarten says local unions will fight her by asserting their power, though how they will do that is unclear. A senior aide to a top congressional Democrat told me that DeVos should be ready for a tough confirmation hearing, but he didn't say anything to suggest there'd be a concerted attempt to oppose her.

Weingarten told me about a letter she got from a teacher in New York's Suffolk County, on Long Island. That teacher had apparently voted for Trump and was now suffering from buyer's remorse. "I made a terrible mistake," the letter said, according to Weingarten. "Please, please fight against this."

The battle is doubtlessly coming to the American classroom, where the nation's culture wars are frequently fought. Of course, DeVos will be ready for the counterattack. She has spent decades fighting for children, for Michigan and for God.