Ronald Reagan came to North Carolina on October 8, 1984, a month before American voters would decide whether to give him another four years in the White House. In 1980, running against Jimmy Carter, he'd won the state by only 39,000 votes, but it was now morning in America again, and the president was in an appropriately sunny mood as his rally began, shortly after noon, in downtown Charlotte.

As is customary in politics, Reagan praised his audience, then himself. Soon, he turned to attacking the Democrats, whom he accused of keeping people "in bondage as wards of the state." They wanted dependents, not citizens. And instead of listening to Americans, liberals would tell Americans what to do.

To illustrate his point, Reagan alluded to a matter of fierce contention across the South: the court-ordered integration of public schools and the yellow buses that frequently made that integration happen, carrying white children to predominantly black schools and black children to white ones.

But there was no cheering, no applause, only the stony silence that accompanies an errant note. And when a reaction did come, it was in the form of a Charlotte Observer editorial titled, flatly, "You Were Wrong, Mr. President." The paper's editors chided Reagan, writing that Charlotte's "proudest achievement of the past 20 years is not the city's impressive new skyline or its strong, growing economy. Its proudest achievement is its fully integrated schools."

Back then, the claim was true. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (the district includes Charlotte's surrounding suburbs in Mecklenburg County) had achieved true racial parity in its schools, and had done so without the violence or rancor that accompanied similar efforts, not only in the Deep South but in Northern cities like Boston and Chicago. In Memphis, Tennessee, opponents of integration buried a school bus. In Charlotte, the buses came and went. Long known as the Queen City, Charlotte had an enviable new nickname: "The city that made desegregation work."

The nickname would not apply today. Charlotte, in 2018, looks like most other American cities, where schools are nearly as segregated as they were before the 1954 Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education, which declared separate but equal schools to be unconstitutional. Some cities, like New York, never really integrated their schools, hiding for decades under the guise of Northern liberalism. Many others complied with court orders, but did so unwillingly and incompletely, without ever convincing people that integration was a public good. Charlotte was the rare city that made its citizens believe in integration, and those citizens in turn made integration work. Their retreat from that experiment has been revealing—and complete.

Earlier this year, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, or CMS, published a report titled "Breaking the Link," which explored the relationship between poverty and education. A single sentence in the introduction grimly sums up the state of things: "If you are born poor in Charlotte, you are likely to stay that way." In a low-poverty school (i.e., a school where less than a quarter of students are eligible for a free lunch and breakfast program), 95.2 percent of students graduate; only 77.6 percent graduate in a high-poverty school, where more than half of students are eligible for free lunch. The latter have younger, less experienced teachers. There are more disciplinary problems at these schools, and test scores are lower.

The links between poverty and education also pertain to race. "For all grade spans, low-poverty schools were composed of mostly white students," the report's authors wrote, "whereas in high-poverty schools, the majority of students were black and Hispanic." This was the toxic nexus that Charlotte had once tried to dispel. And it did so with success, so that its schools made it onto the front page of The Wall Street Journal in 1991. Only a decade after that, the experiment ended, and now the gains of that time have been squandered.

James Ferguson is a civil rights lawyer who worked on the legal effort to desegregate Charlotte's schools. That was 50 years ago. He does not want to believe the work was futile, but a life of fighting discrimination cautions against shows of optimism. History is littered with disappointments, including his own. He was in junior high, at a segregated school in Asheville, North Carolina, when the Supreme Court delivered the Brown ruling. Like many, he thought things would change at once. But they didn't change at all because people in Birmingham, Alabama weren't going to take orders from Washington.

The nation delivered on the promise of Brown only because men and women like Ferguson forced it to, and to have the nation renege on that promise has been crushing. Ferguson is a civil leader in Charlotte, a power broker, and the sadness haunts him; he thought he'd won a battle, when it turns out he lost. "There is no core of people who are actively pushing for school desegregation," he laments. "We're almost back to where we started from."

We, in this case, could mean the entire United States. We came closest to integration in 1988, when nearly half of all African-American children attended majority white schools. Since then, districts have been casting off federal court orders like rusted shackles. The result, a Government Accountability Office report found in the spring of 2016, the number of African-American and Hispanic students attending segregated schools is rapidly growing.

Charlotte was never supposed to be among those districts, though. That was the promise of Charlotte. For many decades, it was a promise realized.

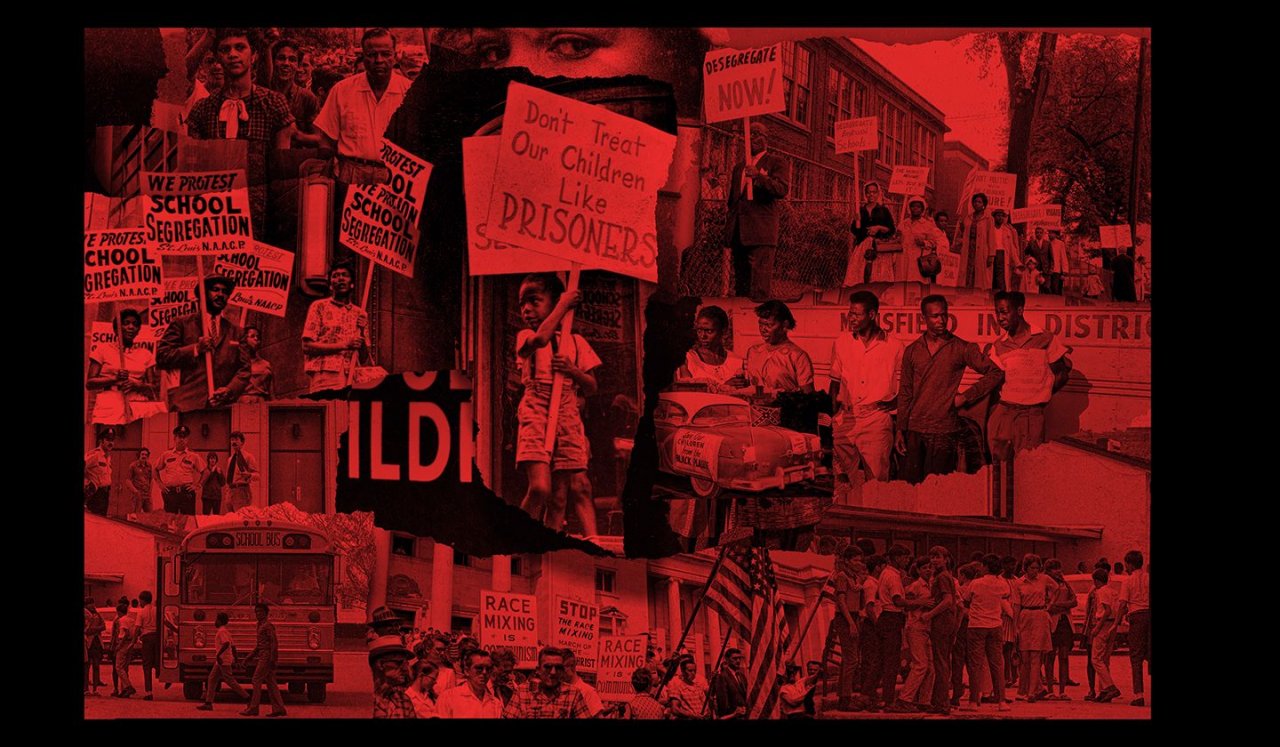

Frightened, White and Middle-Class

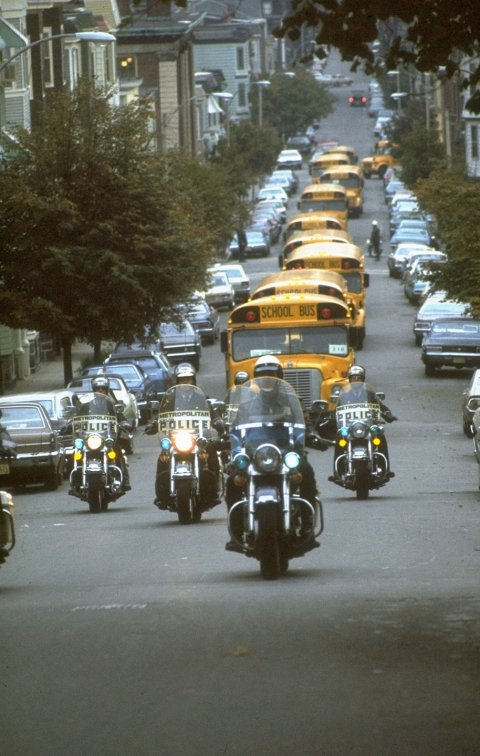

The bus may well be the most potent symbol of African-Americans' struggle for racial equality in the 20th century. In Montgomery, Alabama, a squat yellow-and-lime bus, numbered 2857, became the epicenter of the civil rights movement on December 1, 1955, when seamstress Rosa Parks refused to move toward the back, where blacks were forced to sit. About a decade later, as the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson took up the work of actually enforcing the Brown decision, it was the yellow school bus that became a vehicle of both social progress and deep-seated fears that made that progress so difficult.

Matthew Delmont, the author of Why Busing Failed, has concluded that the first protest by white parents against the use of busing to redress racial imbalances in public schools took place in New York City in 1957. New York was exempt from Brown because its schools were not segregated by law, like those in the Deep South. That made white residents all the more furious, because they felt they had done nothing to segregate schools and should therefore not be forced to integrate them.

Journalists were aware of these fears, and some played to them. A Wall Street Journal article warned that the city's Board of Education "proposes extensive use of city-financed buses to create racially balanced schools." Delmont believes this was the first time a national outlet deployed the specter of "busing" to frighten middle-class whites. (Buses had been transporting children for decades, and plenty of districts were already using racial criteria in zoning decisions to keep schools segregated.)

The fearmongering worked, and it encouraged newspapers and television stations to report with greater avidity on what came to be known as "forced busing." Opponents of busing predictably directed their anger at education bureaucrats, whom they accused of social engineering. As one letter to New York's central schools administration put it, "The Negro is emerging from ignorance, savagery, disease and total lack of any culture. Is it necessary to foist the Negro on the White Americans for fair play?"

Despite a halting effort at integration that began in 1957, little changed in Charlotte during the 1960s. Busing came to the city only after a 1969 federal district court ruling in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Board of Education, a suit brought by an African-American preacher who didn't understand why his son had to attend effectively segregated schools. The judge in the case was a white Southerner without especially strong liberal convictions. But he also understood that there was no legal standing for those who resisted integration. "When racial segregation was required by law, nobody evoked the neighborhood school theory to permit black children to attend white schools closer to where they lived," he wrote. "There is no reason except emotion…why school buses can not be used…to desegregate the schools."

And so busing began in Charlotte on September 9, 1970, with 525 buses serving as the army of integration. White parents protested, and Charlotte, which claimed to be a city of the "New South," anxiously waited to discover whether its claim was anything more than a clever marketing pitch.

Goodbye, White Flight

Integration turned out to look a lot like war. Mobs welcomed buses carrying black children into white neighborhoods. Whites threw rocks and hurled racial taunts. White children stayed away from schools. On the television sets that now graced nearly every home in the nation, Americans watched and wondered if racial reconciliation would ever be possible.

The year was 1974, and the city was Boston, not Charlotte. There, a court order mandated that Irish-Americans in South Boston enter into a busing arrangement with black Roxbury. Feeling that they were being bullied into integration by judges and politicians, aggrieved residents of Southie reacted with shows of violence and rage more associated with the Deep South than this city of patricians and academics.

Meanwhile, 840 miles to the south, things were going just fine in Charlotte, now in its fourth year of integrated schooling. Watching the reports from Boston with confusion and dismay, students at West Charlotte High School, which had quickly become the centerpiece of Charlotte's success, decided to do something novel: They invited students from Boston to come down South, to see that integration could be done peacefully, to the benefit of all students. Five high schools students traveled to Charlotte that November. "I think every KKK member in the South wrote me a personal letter calling me a nigger-lover and threatening me," recalled West Charlotte Principal Sam Haywood to historian Pamela Grundy many years later. He added, "You know, if adults had got out of the way, kids could solve most of the problems."

But adults had helped solve the problem in Charlotte. Specifically, well-off white adults who seemingly had the least to gain from integration. Some of the city's leading families decided they would send their children to West Charlotte High School, a sign that they were invested in the integration experiment. Maybe there was something selfish in this, too—a desire to separate Charlotte from symbols of racial strife like Birmingham and Montgomery. Even so, they put their own children on school buses instead of merely watching as middle- and working-class whites did.

Everyone was uneasy about the experiment. As one African-American student recalled years later, "[People] thought it was going to be racial tension every day. 'Here we go again. Six o'clock news. A riot at West Charlotte again.' Never happened." Whites and blacks made the requisite effort. It wasn't a seamless union, but the rivets held.

Eventually, integration became a normal part of life in Charlotte, which made the city exceptional in the eyes of the nation. During his eight years in the White House, Reagan had appointed 364 judges to the federal bench, many of whom could be expected to execute his conservative, anti-government agenda, which included opposition to busing; his successor, George H.W. Bush, ran a racially divisive campaign predicated on raw fears about black criminality. In March 1991, the video of white police officers beating a black resident of Los Angeles named Rodney King confirmed a new mood of racial hostility—or, even worse, that racial hostility had never gone away.

Two months after Americans learned of King's plight, The Wall Street Journal reported on the goings-on at West Charlotte. In a front-page article, the paper praised the school as a "warm picture of integrated young America," a hazy but hopeful vision of the type of society we have been trying to realize for half a century. "Particularly in a city with a history of racial confrontation," the article said, "it does seem extraordinary. In many urban centers, white flight has left school districts overwhelmingly black…. Not Charlotte. Its school board has steadfastly rejected any proposals to end its forced busing program."

But by the time that article was published, some were already trying to undo the experiment.

'Race Is Not The Issue'

In the early morning of January 17, 1994, a massive earthquake shook Los Angeles. After that, Bill Capacchione remembers, his wife said it was time to leave. She was a native of Southern California, and the quake had rattled her. "If this is not the big one, I don't want to be around for it," Capacchione recalls her saying. He offered Phoenix as a relatively close alternative. Too hot, she countered. Capacchione had gone to college in North Carolina, at Campbell University, so he suggested a city 130 miles due west of that school: Charlotte.

Around that time, a lot of people were thinking of moving to Charlotte; it had recently become the third-biggest banking center in the nation, after New York and San Francisco. The same year that Capacchione arrived, The New York Times wrote of Charlotte's "relentlessly upbeat, look-at-me corporate culture." The city's "downtown, which goes by the appropriately cheery appellation of Uptown, is a vital business center, and its green geography and relaxed, friendly style make it an inviting place," the article said.

The new arrivals may have worked in downtown, but they didn't live there. For the most part, they moved to suburbs to the north and south of the city, where subdivisions seemed to rise overnight. One recent study of land use in the county found that while only 12.5 percent of land in Mecklenburg County had been developed in 1976, 40 years later, that number had nearly quintupled, to 57.6 percent. Even as Charlotte thrived, it was Mecklenburg that grew.

The newcomers, like the Capacchiones, came from the West and Northeast, where schools were severely segregated, but few blamed racism; the segregation of a city like New York seemed to many like nothing more than a historical accident. There was, in fact, nothing even remotely accidental about the forces that turned Brownsville, Brooklyn, or the South Side of Chicago, into ghettos. But because police there hadn't disbanded protesters with water cannons, that segregation was easier to ignore.

Charlotte had confronted its segregationist past, and that confrontation resulted in a remarkably successful school system. But to those who hadn't lived through the early, uncertain years of integration in the 1970s, the busing plan was confounding and not especially welcome. In the suburbs, especially, resistance grew. As early as 1988, a parent complained that Charlotte was "a model for shifting children from one end of the county to the other and not a model for educational excellence by any means."

School officials in Charlotte had sensed a growing resentment toward their integration plan. To fight off the criticisms of whites in the suburbs, they created a number of magnet schools throughout the 1990s, which would draw students from all over the county. (Magnet schools are an attractive solution, promising both academic excellence and integration. But the solution doesn't scale especially well.)

One of the popular new magnet programs in Charlotte was Olde Providence Elementary School, to the southeast of the city's center, which had undergone an expansion in 1992. This was where Capacchione tried to enroll his 6-year-old daughter, Cristina. She was denied admission. Capacchione tried again. But she still didn't get a spot. On September 5, 1997, Capacchione filed a suit against Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, alleging that his white daughter was discriminated against on the basis of her race and, as he explained from the stand, "felt she wasn't smart enough to get into Olde Providence."

Five other families joined the suit. They argued that Charlotte had spent 30 years integrating its schools. The work had been so well done, they claimed, it didn't need to continue any longer. Larry Gauvreau, another recent transplant to Charlotte who joined the suit, judged the school system "fully desegregated" and any suggestion to the contrary "absurd."

On September 9, 1999—29 years to the day since busing began—federal Judge Robert Potter issued his ruling in the Capacchione case. As a private citizen, Potter had opposed the initial 1970 desegregation plan. And he was an ally of Jesse Helms, the state's segregationist U.S. senator. Appointed to the federal bench by Reagan, Potter earned the nickname "Maximum Bob" for his tough sentences. He agreed with Capacchione, writing that, "the Court is convinced that CMS, to the extent reasonably practicable, has complied with the thirty-year-old desegregation order in good faith; that racial imbalances existing in schools today are no longer vestiges of the dual system; and that it is unlikely that the school board will return to an intentionally-segregative system."

With that, Charlotte's experiment with integration had ended, and the city was ordered to wind down its busing program. "The decision," observed The New York Times, "which affects about 28,000 students who now ride buses past their neighborhood schools in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School District, has enormous symbolic significance for the lingering institution of court-ordered busing."

Kids were now much more likely to go to their neighborhood schools. And since the neighborhoods themselves remained segregated, that means they were much more likely to go school with kids who looked like them. This was to some a problem and to others, who cheered the Potter decision, the whole point.

Capacchione was not in Charlotte to celebrate the Potter decision. His wife missed her family, and the Capacchiones had moved back to Southern California. They live there still, down the coast from Los Angeles, in a city called Torrance. Capacchione says his daughter, Cristina, "went to neighborhood schools," to which she was always able to walk. "To me, race is not the issue," Capacchione says dispassionately, decisively. "I didn't think any child should have his or her opportunities limited by race or by where they live."

On the first point, few Americans would disagree, at least in principle. The second assertion is more complex. The entire point of busing was to avoid relegating poor black children to inner-city schools. That couldn't happen unless parents like Capacchione were willing to give up their own access to superior suburban schools. But they had come to expect their own schools—"neighborhood schools," a phrase rich with Rockwellian intimations—as a kind of constitutional right. There is no such right, however, any more than there is an inherent right to traffic lights instead of stop signs.

Capacchione seemed confused about why anyone would want to talk about the court's decision. To him, it was old news. "I probably would do it again," he says of his lawsuit. This isn't bravado. You can hear it in his voice: He has no regrets.

The Cost of Segregation

Keith Lamont Scott sat in his truck, waiting for his son to arrive on a school bus. The truck was parked in a lot at an apartment complex northeast of downtown Charlotte, in an area that's largely poor and the schools are mostly black and Latino. It was September 20, 2016, just a little before 4 p.m. Within moments, Scott would be dead.

Members of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department were in the complex looking for someone else. They said they saw Scott in his vehicle, with a gun. His family insists he was reading. His wife, Rakeyia Scott, took video of what followed. You can see her approaching the several officers who have drawn their guns and surrounded her husband. "Don't shoot him," she says.

But they do. No book was ever found. A gun was. The officer who shot and killed him—Brentley Vinson, a young, black man—was cleared of all charges. Black Lives Matter and other activist groups launched protests that consumed the city for days, as officers in riot gear took to Charlotte's streets like an invading army. The gleaming jewel of the New South suddenly seemed like its sullied Old South counterparts.

The part of Charlotte where Scott was killed makes up what is locally known as a "crescent" of poverty that circles downtown. Several blocks from where Scott was shot is Newell Elementary School, which is 90 percent black or Hispanic; 99.6 of its students are on free or reduced lunch, meaning they live in poverty. Down the road is the Zebulon B. Vance High School, which is 90.7 percent black or Hispanic; 99.8 percent of its population qualifies for free or reduced lunch. The gap in the crescent is to the southeast of Charlotte, where "the wedge" — a cluster of affluent suburbs — grows wider the further into Mecklenburg County it pushes, away from the inner city, into the verdant suburbs where poverty and violence are only the stuff of news reports Scott was killed by two bullets; he was condemned by history and demography, impersonal forces that converged on him on a Friday afternoon.

Those same forces also did their work on Anthony Foxx, only they did so to far more auspicious effect than in Scott's case. Foxx is 46 today, which means he's a few years older than Scott when he was killed. He grew up in Charlotte, attending integrated schools there, including West Charlotte High. He went on to Davidson College, one of the best liberal arts schools in the South, and then to New York University for law school. In 2009, he was elected mayor of Charlotte, the youngest person to ever hold that office, and only the second African-American to do so. Four years later, President Barack Obama selected him to serve as head of the federal Transportation Department.

"I think many of the white kids who went to West Charlotte got as much of a taste of the black experience as any white person was likely to get at that time," he says. "Black kids like me, we saw whites as our counterparts. It was as equal a position as I've been in at any time of my life, even since."

Foxx warns against mythologizing Charlotte's integrated past. He remembers, for instance, that there were few African-American students in advanced classes. Still, the impact of the integrated experience has stayed with him. "I think that whites and blacks and others whom I went to school with in those years are certainly more well rounded and understand American culture in a more true light than most of us do," he says. "Because they saw, even for a brief period of time, the tapestry that the country has."

By the time Foxx became mayor, the Capacchione v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools decision had largely resegregated schools in Charlotte. "Neighborhoods became more segregated following the declaration of unitary status," says Amy Hawn Nelson, a University of Pennsylvania education researcher who has closely studied Charlotte's demographics (a school district has reached "unitary status" when it is no longer deemed segregated). The result, Nelson says, was that real estate brokers could lure buyers by promising that their children would be guaranteed a spot in some well-regarded suburban school, since the fear of those children being bussed elsewhere was pretty much gone. And what typically burnishes a school's reputation? Racial composition, not academic achievement. "Even when you look at school quality metrics, Nelson told me, "white families are more likely to pick a white school rather than a high performing school."

There have been efforts by school Charlotte-Mecklenburg superintendents—who are independent of the mayor—to skirt the ruling by creating more magnet schools and implementing "student reassignment" plans that modestly push for reintegration. Only the countervailing push is stronger. The internet allows for subatomic analysis of each school's demographics and academics. If they can get a child into Providence, one of the best high schools in Charlotte, they will. Who wouldn't? And thanks to Capacchione, they can do so without resorting to a federal lawsuit.

Most of these people are liberals: Mecklenburg County voted for Obama twice, while Hillary Clinton nearly doubled Donald Trump's vote total in 2016. Yet it is one thing to vote in a school gymnasium for a politician you have never seen, quite another to watch your own child ascend the steps of a yellow bus. It used to be that voting and public education were seen as part of the same set of behaviors collectively called civic participation. No longer so, not when a scholarship to Stanford hangs in the balance. As the education writer Nikole Hannah-Jones has put it: "We began moving away from the 'public' in public education a long time ago. In fact, treating public schools like a business these days is largely a matter of fact in many places." Once citizens, we are now customers.

Foxx has watched the city's resegregation with dismay. What he experienced at West Charlotte should have been the start of something hopeful; instead, it was an ending. "It's been interesting to watch my friends at that time more or less revert back to the areas of town they grew up in," he says.

Interesting, yes, and in the case of Scott, tragic. School resegregation did not kill him, of course, but it contributed to the creation of a dual society. After the Scott killing, the sociologist Clint Smith wrote in The New Yorker that we "cannot disentangle the state-sanctioned school resegregation that poor black students in Charlotte experience from the police killing of a black man waiting for his son to get off the bus from elementary school."

We have known as much for a long time. After the civil unrest of the summer of 1967, President Johnson set up a National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, better known as the Kerner Commission. Written as the smoke was still clearing from riots in Newark and Detroit, the Kerner report found many reasons for the unrest, public schools among them. "The hostility of Negro parents and students toward the school system is generating increasing conflict and causing disruption within many city school districts," warned the report. It can just as readily serve as context for the rage of Black Lives Matter activists who protested in Charlotte as Scott was being laid to rest.

Our thinking is much more data-driven today, yet as far as school integration is concerned, the conclusions of scholars are not at all different from those of the Kerner Commission. Rucker Johnson, a labor economist at the University of California, Berkeley, has studied the effects of resegregation. In a forthcoming paper, he compared the life outcomes of students who'd gone to integrated schools and those who went to schools were courts had lifted integrated orders. Johnson found that resegregation "caused significant increases in the likelihood of being arrested, of being convicted of a crime, and being incarcerated in adulthood for African-Americans." They were also likely to earn less.

As for whites, who experienced no deleterious effects from integration, Johnson found that resegregation would lead them to "have no racial diversity among their friends in adulthood, to live in neighborhoods in adulthood without racial diversity, to express significantly stronger preferences for same-race partners, and were significantly less likely to have ever been in an interracial relationship."

Johnson calls resegregation a "market failure" because it leads to outcomes that are not only unfavorable but also expensive. It is, after all, much cheaper to educate a child than to incarcerate an adult.

'The Miseducation of Our Kids'

Today, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools are led by Clayton Wilcox, who came to North Carolina from suburban Maryland. Wilcox admits that the kind of muscular integration once conducted in Charlotte is no longer possible. "I don't think there's any appetite except for a very few folks," Wilcox tells me after I asked about the possibility of bringing busing back. "The methods of yesterday," he says, no longer apply. "You have to create great schools everywhere," in reference to providing adequate funding to inner-city schools. Research by Johnson of Berkeley confirms that increased spending can ameliorate some, if not all, the effects of resegregation. Then again, spending is as anathema as busing to some.

Wilcox was not yet in Charlotte during the Scott shooting or the protests that followed. He references the killing as evidence of something amiss in the city, as well as its schools. "We are all in this together," he says. "Many of the things we fear are the result of the miseducation of our kids."

But some don't share that sense of togetherness. Last year, Charlotte-Mecklenburg passed a $922 million bond measure that angered people in the northern reaches of Mecklenburg County, an area that is rapidly growing. No schools will be built there. A local county official named Jim Puckett who opposed the bond measure, believes the shortage of schools in the county's north (where not everyone is white) was intended to force residents of the suburbs to send their children to schools closer to central Charlotte, integrating them without quite having to say so.

"You've got this angst in the suburbs," says Puckett. "They're not getting the capital resources." Some of the northern suburbs have even threatened to secede from Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, thus creating their own school districts. School secession has become a popular way to avoid integration, especially in states controlled by Republican legislatures that have made it easier for municipalities to cleave from larger school districts. A report published last year by the nonprofit EdBuild found that 71 districts around the nation have tried secession since 2000. More than half have been successful; invariably, these splinter districts are whiter and wealthier than the district they are leaving.

"Parents tend to be rather self-serving," says Puckett, the Mecklenburg County official. "They come to the table with certain beliefs." And the prevailing belief in Charlotte, he says, is that the public schools are not working. Whites flee for the suburbs; African-American parents, meanwhile, are choosing charter schools, which have become symbols of voluntary resegregation.

"I don't think the city of Charlotte would ever abandon at-risk kids," he says. "That's just not gonna happen."

It is more likely that kids will abandon Charlotte's schools.

'We Sold Our Soul'

There is a famous photograph that shows Dorothy Counts on the first day of school. It was taken on September 4, 1957, as she walked to Harding High School to start the ninth grade. Counts wears a plaid dress with a long white bow; to her left is her father, in a white shirt and slacks, looking grimly ahead. The two are surrounded by jeering whites. In one of the famous photographs from that morning, white hands make devil horns from behind Counts. She looks off into the distance, mouth askew. She is willfully ignorant of the bigots enveloping her like a thick cloud of mosquitoes.

Counts only wanted to be a student. But because of her race, she was, above all, an agent of integration. She did not last long in Charlotte's integrated schools. The abuse of local whites had its intended effect, and after several weeks she was shipped off to live with family in Philadelphia. She completed her schooling there. It would be more than a decade until Charlotte seriously started integrating its schools.

Today, Counts (now Dot Counts-Scoggins) lives in Charlotte again. She worked for years in early childhood education but is now retired. Once maligned, she is now celebrated. The library at Harding has been named after her. Charlotte magazine deemed her one of the city's essential citizens. "In some ways, we need her now as much as ever," the magazine said in November, lest Charlotte forget in this age of renewed animosities what it did to her all those years ago.

Counts-Scoggins has not forgotten. "Well, it's very disappointing to me when I look at what has happened in Charlotte," she says of the un-integration of the city's schools. "I tell people, 'This didn't happen in Charlotte overnight. This was something that was happening, and people just sort of ignored it."

Integration is difficult work, the work of generations. It may not be especially gratifying to those who must undertake it. Segregation, on the other hand, feels natural enough. Difficult to expel, it is always eager to return. Integration may show its benefits in 50 years, but who wants to wait that long? We are an impatient species, increasingly skeptical of things unseen.

And yet segregation takes a toll. Justin Perry was at West Charlotte High when he heard about Judge Potter's decision in 1999. He remembers leaving school and going downtown, to the courthouse, to protest.

Perry understood that the judge had exploited racial fears to destroy one of the few places where those fears were addressed, by blacks and whites alike. "In our space, we actually talked about these differences," says Perry, who is African-American. He is too young to have lived through segregation. Nevertheless, he grasps that "busing" has never been about the use of vehicles to transport children to school. "This is not about busing," he says. "It's about what the end of the ride leads to."

For Perry, who still remembers the day integration ended in West Charlotte, we are all worse off for it. After graduating from high school, he went on to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, from which he received both undergraduate and graduate degrees, the latter in social work and counseling. Today, he works with young people in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. Some of them come from the wealthy white suburbs to which parents fled in the 1990s so that their children would not have to attend integrated schools. Instead, these students now attend what Perry calls "real-estate orchestrated" schools, where the pressures of achievement can lead to stress, anxiety and other psychological maladies.

"You can't have a high-quality education without diversity," says Perry. The rollback of integration efforts, Perry believes, signals a deeper social breakdown, an atomization of American society. "We sold our soul," he says, "and now we're gonna have to deal with it."

The process will likely be painful, just as it was the last time around. Last year, students from Ardrey Kell High School shouted racial slurs at a football game against William A. Hough. "Black boy, you better watch your back! Black boy, you better keep your head on a swivel!" they screamed, apparently drunk, as middle school students sat nearby.

The principal of Ardrey Kell apologized, but few were satisfied; many saw the dutiful workings of damage control. Such an incident would have been unthinkable when Perry went to West Charlotte, when it felt like a suture was about to close. Now, it is open again, and the wound is festering. Only the pain is unequally distributed. Ardrey Kell is a majority white school; only 21 percent of the student body is either black or Hispanic. It is widely regarded as one of the best schools around. Hough is mostly white, too.

West Charlotte, meanwhile, is 99 percent minority and well below state averages on both English and mathematics standardized tests. Once the pride of Charlotte, this high school is now in need of fixing. And Charlotte itself, once the beacon of something hopeful and new, has gone back to its old ways.