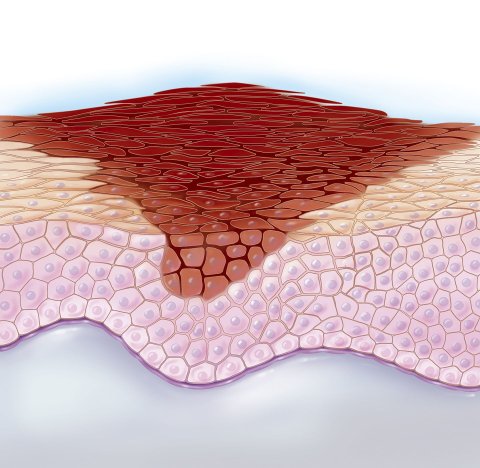

Wear sunscreen, always. Not just at the beach but at all times, even in winter. When it comes to skin care, that Michael Pollan–esque adage is one that we can all agree on: Regular use slows signs of aging and prevents exposure to the harmful ultraviolet A and ultraviolet B rays that cause skin cancer.

But for many Americans, sunscreen remains a fraught subject. Products that use zinc oxide, the most effective barrier between the skin and cancer-triggering UV light, usually leave the skin with that chalky white cast sometimes called "lifeguard face." And products that avoid zinc oxide by using alcohol-based chemicals that the skin more readily absorbs have prompted health concerns that deter many Americans from using them.

Sunbathers elsewhere—in France, Japan and Korea—have a lot more options, with access to sunscreens that absorb better, aren't greasy and don't leave the face tinted white. Although most American sunscreens offer sufficient protection against sunburn-causing UVB rays, European and Asian formulations come equipped with the chemicals Tinosorb S, Tinosorb M, Mexoryl SX and Mexoryl XL—filtering agents that also stave off signs of aging and subtler damage caused by UVA rays.

Since 1978, sunscreen in America has been regulated as an over-the-counter nonprescription drug, unlike in the European Union, where it's considered a cosmetic. To qualify as a sunscreen in the U.S., a product must contain no more than three of the 21 filtering agents that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The filters range from chemical blockers like para-aminobenzoic acid, which absorb ultraviolet radiation and convert it into heat energy, to physical blockers such as zinc oxide, which reflect and scatter the sun's harmful rays before they can penetrate the skin. And because the FDA considers them drugs, any newly invented chemicals for repelling the sun's dangerous rays go through years of testing and evaluation before they can hit the market.

Applications for the review of newer sunscreen ingredients often flounder for years—sometimes as long as a decade—in backlogged purgatory at the FDA; the last time a new ingredient was allowed into American sunscreens was 1999. In 2002, the agency established the Time and Extent Applications process to fast-track the review process on new ingredients that were already available and in widespread use overseas, but it resulted in no decisions, frustrating both skin cancer groups and dermatologists. "Even though they're used by tens of millions of people all over the world," says Dr. Darrell Rigel, a clinical professor of dermatology at New York University's Langone Medical Center, "they're still not available here."

In 2014, after aggressive lobbying from sunscreen advocates, cancer awareness groups, dermatologists and manufacturers, the Sunscreen Innovation Act made its way through the House and the Senate and was signed by President Barack Obama. The legislation required the agency to clear its decades-long backlog of chemicals under review and report regularly to Congress. It also imposed a 180-day deadline for a decision.

The results were not quite what the act's backers had wanted. By January 2015, the FDA had issued rejections for six of the eight pending applications, and by February, it had denied the remaining two. Its defense was that the act demanded the agency issue only a decision, not an approval. The FDA further claimed that it didn't have enough scientific information on the effects of the pending molecules when absorbed into the skin to officially recognize them as safe and effective. The agency also insisted on more data from the manufacturers, effectively engineering a stalemate that remains unresolved three years later. In an emailed statement, FDA spokeswoman Sandy Walsh notes that as of last month, no additional data for these eight ingredients, nor any additional ingredient requests, had been submitted.

Some rigor is warranted. The Skin Cancer Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) both recommend generous use of sunscreen as a skin cancer prevention aid, advising frequent reapplication every two hours and not just at the beach. Walsh's email went on to say that sunscreen today is used more frequently and in greater quantities than it was in the 1970s, when sun protection was conscribed to fair-skinned people needing to prevent sunburns during the summer. Back then, the ability of UV-filtering agents to penetrate the skin was not widely recognized. The change in how we use sunscreen, Walsh says, led to questions at the agency about the safety and effectiveness of chemicals that block UV rays. But the FDA refuses to commit to a timeline for ruling on any of the eight pending compounds, and because additional data has yet to be submitted, the agency cannot proceed with its review.

That delay may be interfering with our health. According to the most recent data provided by the CDC, 76,665 people were diagnosed with melanomas of the skin in 2014, and the American Cancer Society estimates that about 91,270 new melanomas—the deadliest form of skin cancer—will be diagnosed in 2018. In a country where skin cancer was declared a public health crisis by the surgeon general, access to advanced sun safety should be widespread. Instead, the sunscreen industry remains frozen in time.