Updated | They get lonely. They miss their friends and family. So, despite the danger of exposing themselves to retribution, Russian defectors hiding abroad make phone calls or send emails to relatives in the motherland. And when they do, the Kremlin is listening. "It's easy to find us," one defector in the U.S. tells Newsweek, "if they are really determined."

While phone calls and emails open channels for Russian eavesdroppers to locate defectors, relatives visiting from back home make it even easier. Agents can track them to a defector's doorstep.

Some American security sources say there has been an uptick in Russian activity in the U.S. in recent years; suspected agents have been spotted cruising the neighborhoods of some defectors protected by CIA security teams. The FBI and CIA have been "bringing people out of retirement, people who worked against the Russians in the 1990s" to cope with the challenge, the defector says, speaking anonymously out of fear for his personal safety. (The CIA declined to comment. The FBI did not respond to questions about Russian activity in America.)

Over the past month, U.S. counterintelligence agencies have been especially on edge. A leading factor: the March 4 nerve agent attack on Sergei Skripal, a former mole for British intelligence, in a shopping mall in Salisbury, England. London and Washington blamed Moscow, which denied any role in the attack.

"Everyone's been on high alert since the Skripal poisoning," says Michelle Van Cleave, head of national counterintelligence under President George W. Bush. On March 29, another former Russian double agent in the U.K., Boris Karpichkov, reported that he'd been warned that Kremlin agents were coming for him too. "Be careful, look around, something is probably going to happen," an old comrade told him in mid-February, according to NBC News. "It's very serious, and you are not alone."

Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, who was visiting him from Russia, were assaulted with Novichok, a lethal chemical agent invented by Soviet-era biowarfare engineers in the 1980s. The former mole was slow to recover; a month after the attack, Skripal and his daughter were said to be out of danger.

A similar assault in the United States is not unthinkable, say CIA veterans with long histories with Moscow. The Russians "largely got out of this business in the mid-1970s," says former CIA analyst and Russia specialist Mark Stout, but with the rise of Vladimir Putin in the 1990s, they got back into "tracking down and hunting defectors."

Two former CIA station chiefs in Moscow don't rule out such audacious attacks in the U.S. "Putin has demonstrated there are no limits to the methods he would use to target Russia's 'main enemy' and our allies," says Daniel Hoffman, a 30-year agency veteran. "The attack on Skripal should be ringing alarm bells for all NATO member countries, including the United States, that something like that could happen here." But while Moscow has "always sought to locate Russian defectors in the U.S. and Britain," fellow agency Russia hand John Sipher says, it also "attempts to lure them back to Russia" with the message that "all is forgiven."

That worked pretty well in the waning days of the Cold War, when as many as 40 percent of Russian defectors, like the infamous Vitaly Yurchenko, took the bait and returned home, two agency veterans say. "Often it was because they were homesick, lonely and having great difficulty adjusting to life in the West," says one, speaking on terms of anonymity because such matters remain highly sensitive. "A simple thing like choosing a tube of toothpaste was difficult—too many choices." Because they were unable to speak with family and friends behind the Iron Curtain in those pre-internet days, "daily existence became overwhelming."

No longer. The recent string of events suggests Moscow may have abandoned the lure for the hammer. In 2016, an official British inquiry implicated Putin in the 2006 radiation-poison murder of Alexander Litvinenko, a former Russian intelligence officer living in exile in England, but the uproar faded without diplomatic consequences. The Skripal hit, says former FBI intelligence analyst Aaron Arnold, "could be...a litmus test to see how far people would let them go."

Not far, judging by the furious response of many European leaders, led by British Prime Minister Theresa May, who expelled scores of suspected Russian spies working under official diplomatic cover. President Donald Trump declined to join the Europeans in their harsh criticism of the Kremlin, but the administration booted 60 Russian diplomats from the U.S. and shuttered the Russian consulate in Seattle. Moscow responded in kind, expelling 60 U.S. diplomats—plus 59 from 23 other countries—and closed the American consulate in St. Petersburg. On April 6, the U.S. added new sanctions against 38 Russian oligarchs, their companies and senior Kremlin officials for "malign activity," including attempts "to subvert Western democracies."

Some spy veterans raised doubts about the Kremlin's role in the Skripal affair. And the Russian defector who spoke with Newsweek called the hit "very unprofessional" because it not only failed to kill its target but inevitably pointed to the Kremlin. The U.K.'s top military lab also said it could not identify "the precise source" of the highly engineered weapon.

And why Skripal? the defector asked. The former officer with the GRU, Russia's military intelligence agency, had been unmasked as a British mole years earlier and wrung dry under interrogation before being released in a trade for 10 Russian spies arrested in the U.S. in 2010. "He had no more secrets with him," the defector says. "He was no threat to Russia." More likely, he says, some former GRU comrades whom Skripal betrayed to British intelligence were taking revenge, using "idiots" in the Russian mob to carry out the "amateuristic" hit. He also pointed to a documentary on state-controlled Russian media saying stocks of Novichok had gone missing.

Those are Moscow's lines too, as it turns out. Russia's ambassador to the U.S., Anatoly Antonov, said Skripal "spent five years in Russian jail. So it was enough time for us to know everything that he knew. "Why," he asked NBC News, "we should make revenge?"

That's easy, Hoffman says. "Putin wanted to whip up his electorate with anti-Western rhetoric" before the March 18 presidential election. And he was assured of "an intense reaction" over Skripal from May, who was home secretary in 2006 when Litvinenko was fatally poisoned by plutonium. The expulsions, Hoffman says, allowed Putin to "portray Russia as a besieged fortress, which only he could defend."

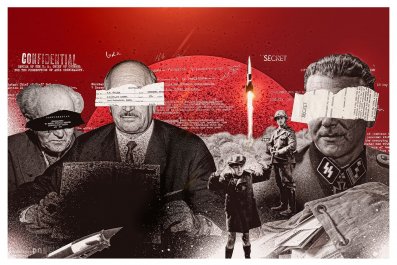

The Kremlin, its critics point out, has a long history of none-too-subtle assassinations. A Russian agent murdered former revolutionary Leon Trotsky with an ice ax to the head in Mexico in August 1940. Six months later, an outspoken Russian defector, Walter Krivitsky, was found in a pool of blood in his room in a Washington, D.C., hotel. Unaware he was on a Soviet hit list, investigators concluded he had committed suicide.

Last year, in Washington, D.C., police officially concluded that Putin's former media chief, Mikhail Lesin, died from multiple falls in his hotel room during a drinking binge. But "everyone thinks he was whacked and that Putin or the Kremlin were behind it," an FBI agent recently told BuzzFeed. In February, the news site also surfaced evidence implicating Russia in 14 suspicious deaths on British soil that the U.K. government had largely ignored.

In January, Democrats on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee issued a report warning that the long arm of Russian intelligence might well reach into the United States and take somebody out. "The trail of mysterious deaths, all of which happened to people who possessed information that the Kremlin did not want made public, should not be ignored by Western countries on the assumption that they are safe from these extreme measures," it read.

Putin said as much after the FBI rounded up Anna Chapman and nine other deep-cover Russian "illegals" in the United States in 2010. Whoever betrayed them would suffer. "It always ends badly for traitors," he said. "As a rule, their end comes from drink or drugs, lying in the gutter. And for what?"

Meanwhile, the defector is fatalistic about his chances of living peacefully into old age here. "I know it's going to happen to me sooner or later," he says. "All I can do is renew my life insurance. If they send a professional, I'm done."

Correction: A previous version of the story said Leon Trotsky was murdered by an ice pick to the head. He was killed with an ice axe. This story has also been updated to include a version that appears in the April 20, 2018 version of Newsweek magazine