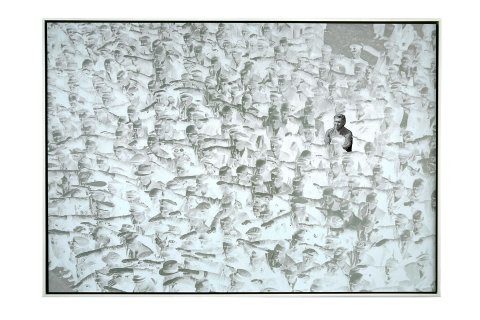

Hank Willis Thomas came across the photo in 2014. The artist, whose work deals with identity, history and popular culture, often employs vintage images in his art. This one, taken in 1936, is of a crowd of Germans in a Homberg shipyard. Adolf Hitler has arrived to christen a ship, and as thousands "Seig Heil" the führer, one man stands, arms folded, a solitary figure of defiance in a sea of complicity.

Willis learned the man's name, August Landmesser, and that he was married to a Jewish woman. Somehow, Landmesser survived the war, and his gesture, captured nearly 80 years ago, was a spark for "What We Ask Is Simple," Thomas's latest show. "What I think about when I look at the photo is that if I had been standing in that place, would I have that courage?" the artist says. "When everyone around me is doing the same thing, would I stand up for what I believe in? That is what this whole body of work is about."

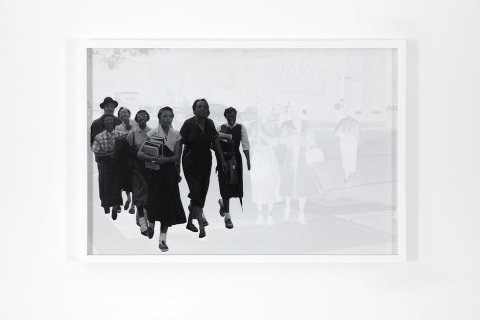

The show, divided between Jack Shainman's two Chelsea galleries in New York and running through May 12, features 46 works based on photographs of 20th century protest movements around the world. ("What We Ask Is Simple" is a phrase from an American Civil Rights protest sign.) Images include the 1913 funeral procession of militant suffragette Emily Davison; a black 15-year-old who carried the American flag 54 miles through Alabama, from Selma to Montgomery, in 1965; members of the American Indian Movement seizing Wounded Knee in 1973; and South Africa's 1976 Soweto uprising. In that last devastating work, a black student holds up his arms in supplication as snarling police dogs strain at their leashes.

Thomas became familiar with many of these images when he was a child. His mother, Deborah Willis—a photographer, photo historian and MacArthur "Genius" Grant recipient—worked as a curator at New York's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Thomas spent hours in the archives, as entranced by 20th-century photography as other children are by Legos. When he grew up, he trained as a photographer, and his conceptual work often entails years of patient research. "As my mother's son, I'm very interested in looking at the past through the lens of the present."

For his 2010 show at the Brooklyn Museum, "Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America, 1968–2008," Thomas appropriated ads from the year of Martin Luther King's assassination through the election of Barack Obama, stripping away text, logos and any branding to showcase how advertising has commodified the African-American male body. He repeated the idea in 2015, this time focusing on white women. That advertising is racist and sexist wasn't surprising; the revelation was how insidious and political that messaging can be, and how much of it we miss or take for granted.

"All my work is about framing and perspective, history and context," Thomas says. "And I thought, How do I shine a light on history in a different way, making the moments feel current and allowing a new relationship to them? And then I was looking at this material called retroflective—even the name implies looking back."

The material is the coating commonly used to increase the nighttime visibility of traffic signs and clothing. For the new show, Thomas employed a process of silvering, half-tone screen printing and 3-D image capture ("I still barely understand how it works," says Thomas with a laugh) that allows each work to be viewed in multiple ways. When dimly lit, only selected elements or figures, like Landmesser, are visible, surrounded by a ghostly field of white; as the light brightens, or if you take a flash photograph with your phone, the entirety of the original image—its context—is revealed. The retroflective, while dramatically highlighting moments of extreme courage, also, to some extent, allows the viewer to step into the role of image-maker.

It isn't lost on Thomas that the result recalls the dying art of film processing, which began disappearing with digital photography. "For me, it's partly about making these images fleeting and precious in a way that I used to feel emotionally when I was printing," he says. "It's almost like the revelation of the darkroom experience, where the images come out of nowhere."

Thomas's work often emphasizes the perennial fight for equality, and how perception can trump reality when it comes to change. "What We Ask Is Simple" is certainly timely as intolerance and extremism surface yet again. And, yes, asking yourself if you have courage is simple enough. It's the answer that's hard. You can't know "until you're tested," says Thomas. "It's often people in the weakest positions who choose to put themselves on the line. And they are so easily erased—some might say whitewashed—and written over."