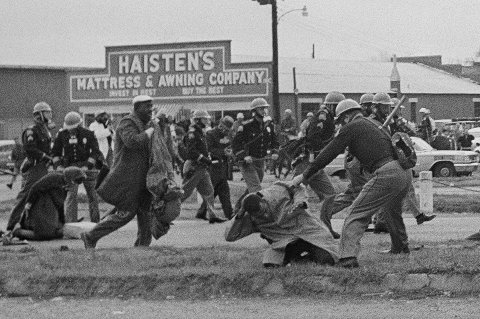

Robert F. Kennedy was killed 50 years ago on June 6—the third in a trio of high-profile assassinations during that decade, the bloody coda to an era of political violence. Today, in our divided, uncivil time, it's worth remembering that Americans survived the horrors of the 1960s and early '70s, which began with the murder of Robert's older brother, President John F. Kennedy, in 1963. But 1968 was something of a watershed: "The year that shattered America," as Smithsonian has called it, demolished the hippie fever dream of the '60s with an explosive cocktail of escalating war, racially charged riots, police brutality and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and then RFK.

There was no 24-hour news cycle back then. Social media was not spreading hate or forging divisive bubbles. The president wasn't fanning flames with regular tweets, covert Russian hackers weren't propagating fake news, and books proclaiming the end of democracy hadn't become a lucrative sideline for publishers—all of which exacerbates our current turmoil, which can feel intractable.

And yet, in 1968 we experienced far worse. "As strange and terrible as these times seem—and they are indeed strange and terrible—it's hard for younger people who are despairing over Trump to imagine what it felt like to my generation, coming of age in the late 1960s," David Talbot, author of Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years, tells Newsweek. "A hideous imperial war that kept grinding on and on, despite massive protests in the streets; long-repressed racial rage exploding every summer in our cities; a Washington power structure that seemed incapable of understanding these protests and eruptions, let alone do anything substantial about it."

Peter Goldman, who wrote for Newsweek at the time, remembers "a widespread sense that we were in big trouble. The foundations of the country we knew were crumbling. Our popular culture was changing." America, Goldman says, seemed to have "come loose from its moorings."

And Robert Kennedy was, for a moment, the man who could lead the nation out of darkness. RFK had been his older brother's attorney general and remained in that position for several months after Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as president. But he left to run for the U.S. Senate from New York in 1964 and won the seat, veering further and further left—well beyond JFK's more conservative ideology—championing the poor, civil rights and labor activism and speaking out against the Vietnam War.

RFK entered the 1968 presidential primary late, announcing on March 16. He would challenge Johnson and Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy, who was running on an anti-war platform. But unlike his rivals, the Ivy League–educated Kennedy had a remarkable ability to speak to both black and working-class voters, creating a coalition in a time of intense political antagonism. "What other reason do we have really for [our] existence as human beings unless we've made some other contribution to somebody else to improve their own lives?" he said in one of his speeches, typically peppered with erudition and an almost ecclesiastic, Catholic compassion.

In an interview with Kerry Kennedy for her book, Ripples of Hope, commemorating the anniversary of her father's assassination, Barack Obama (who turned 7 in 1968) says he took inspiration from RFK's ability to change his views, becoming more progressive on race and poverty. "By the time he was running for president, you had a sense of somebody who had really gone inward and examined himself," Obama said.

The rich and privileged Kennedy was also remarkably opposed to the interests of big business (a 1968 Fortune article called him the most unpopular candidate since FDR). The gross domestic product, he famously said in a post-announcement speech in Republican Kansas, "measures neither our wit, nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile."

LBJ quickly realized the implications of Kennedy's popularity; he pulled out of the race on March 31, leaving it wide open.

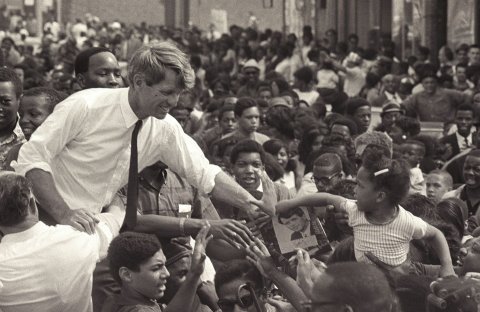

Footage in a new Netflix documentary series, Bobby Kennedy for President, shows his charisma. That, coupled with a nation still mourning his brother's death, led to profound public yearning. As he plunged into crowds, people would grab his hands, yelling, "God bless you!" In an introduction to her book, Kerry Kennedy writes that her father's hands were rubbed raw and his shirt cuffs torn at the end of each campaign day.

The nation, meanwhile, was drowning in death. The Tet Offensive that started in January of that year led to the war's bloodiest period for U.S. troops, with 1968 its deadliest year: 16,592 American soldiers killed. The year would also see a peak of more than half a million men fighting the war.

And then, on April 4, just weeks after RFK entered the race, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at a motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Anger and despair erupted in black communities across the nation, with riots in cities like Chicago, Baltimore and New York. Kennedy was campaigning in Indianapolis that night, and local police urged him to cancel his rally, held in a mostly black neighborhood. Kennedy wouldn't hear of it, speaking extemporaneously with a few jotted notes. He quoted Aeschylus, calling him "my favorite poet": "Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God."

Sad-eyed but with a dazzling smile, Kennedy stumped across the nation through April and May. His chance of winning the Democratic nomination wasn't certain, but the likelihood was strong. Millions—progressives and others—saw in Kennedy the light and love that could, as King had preached, drive out darkness and hate.

But on June 5, the night of the California primary—then the last one in the Democratic primary season—any hope of salvation was destroyed. Kennedy was shot to death in the kitchen area of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles at what was supposed to have been his victory party. In the hours before his murder, as success became clear, supporters were ecstatic. "It was like everything you could ever hope and wish for was going to happen," recalled labor organizer Dolores Huerta.

Sirhan Sirhan, a Palestinian incensed over Kennedy's support of Israel, was convicted of killing Kennedy and remains in prison; the incident is considered by some to be the first act of violence on American soil stemming from the Arab-Israeli conflict. A few months later, benumbed Democrats nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey at a Chicago convention scarred by protests and police violence. Richard Nixon was elected president in November. Two years later, National Guardsmen killed four students at Kent State University in Ohio. By 1974, Nixon was facing impeachment and resigned.

Author Talbot was 16 and a passionate supporter of Bobby Kennedy when he heard the news of the assassination on his car radio. "That burst of gunfire not only mortally wounded RFK, it deeply damaged the dreams for a better America that had been embraced by millions of people like me," he says. "For many in my generation, these wounds haven't healed; we still have trouble believing in our country's future."

Young Americans, energized by the enormous promise of JFK, RFK and MLK, were left reeling. Journalist Jack Newfield, present at Bobby's murder, eloquently summed up the feeling in his 1969 memoir, RFK: "Now I realized what makes our generation unique, what defines us apart from those who came before the hopeful winter of 1961, and those who came after the murderous spring of 1968. We are the first generation that learned from experience…that things were not really getting better, that we shall not overcome. We felt, by the time we reached thirty, that we had already glimpsed the most compassionate leaders our nation could produce, and they had all been assassinated. And from this time forward, things would get worse: our best political leaders were part of memory now, not hope. The stone was at the bottom of the hill and we were all alone."

That sense of despair, however, was not shared by all. Representative John Lewis, the longtime congressman from Georgia and a civil rights leader, tells Newsweek that he and other progressives fought to maintain faith in the future. "During the '60s, in spite of [those three] assassinations, we never became bitter," he says. "We never became hostile. We never hated. We kept holding on—we kept dreaming. Although something died in all of us, we kept the faith. We kept dreaming for a better day."

And better days did come. Fifty years on, the U.S. poverty rate is dramatically lower, and tolerance and equality are dramatically higher: Gay marriage is legal, and there is increased awareness of discrimination against women and minorities. Obviously, there is still much to be done, yet if we have learned anything, it is that Americans can turn again toward hope.

Kennedy adviser and labor leader Paul Schrade was at the Ambassador Hotel and was shot in the head during the attack. His spiritual recuperation took much longer than his long physical recovery. He left his job as an organizer and went back to work in an aerospace factory for several years, "because I wanted a quiet place," he tells Newsweek. But Schrade joined peace marches in the early 1970s—which he credits with leading to the end of the Vietnam War. And while he doesn't think the country has ever really come back from the era of assassinations, at 93 he still has unwavering faith in the power of progressive movements. "I am as appalled at Trump as many people, but we are, I think, turning a corner with Black Lives Matter, the #MeToo movement, and with the students against guns."

Obama maintains his belief in the country that elected him as its first black president, finding lessons, even inspiration, in America's worst moments, as RFK did. "If we're going to talk about our history, then we should do it in a way that heals, not in a way that wounds, not in a way that divides," he said at a rally last October. "That's how we rise up. We don't rise up by repeating the past. We rise up by learning from the past and listening to each other."

"In spite of what is happening today," says Lewis, "we shall, and will, overcome."