There's a low buzz at House of Memories, a popular restaurant in Yangon, where two 20-somethings in T-shirts are listening impatiently to a visitor's questions about Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of Myanmar. Some 600 miles away from the main city, the military allegedly has been ethnically cleansing Rohingya Muslims in the western state of Rakhine, and the visitor wants to know if they think Suu Kyi has condoned these actions.

The two munch on seafood salad and batter-fried vegetables, point out the Japanese tourists dining at the next table and murmur asides to each other before one finally declares, "I love her," his tone at once plaintive and defiant. "And anyway," he says of the Rohingyas, "those are not Burmese."

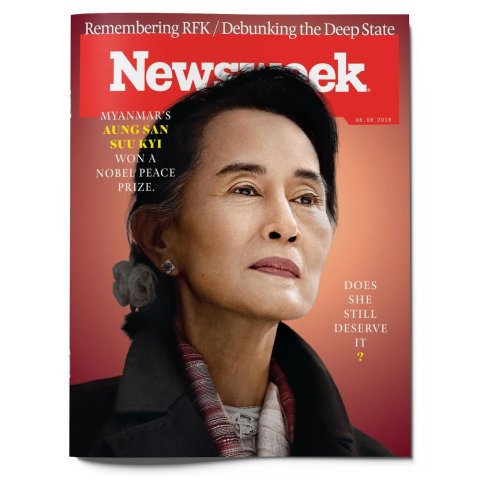

That's a common refrain among Myanmar's Buddhist Burmans, the country's ethnic majority. They see Suu Kyi, 72, as one of their own. She's the adored youngest daughter of Major General Aung San, who led the fight against the British before rival politicians assassinated him just months before London granted the country independence in 1947. She's the Oxford-educated patriot who opposed the military regime, which seized power in 1962 and introduced totalitarian rule. She's the defiant dissident who became the face of nationwide protests against the military in 1988, before the army cracked down on them, killing thousands of citizens. The Lady, as Suu Kyi is known in Myanmar, spent more than a decade under house arrest. Her resistance was so fierce, she even refused to travel to England for the funeral of her British husband, Michael Aris, for fear that the junta would not let her return home. In 1991, she won the Nobel Peace Prize for her commitment to nonviolent struggle, democracy and human rights.

That struggle continued for another two decades, and by 2015, then-President Thein Sein decided to hold a free election in a bid to make sure the West didn't reimpose crippling economic sanctions against the country. Suu Kyi's party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), won and formed a civilian government that the former dissident now heads as state counselor.

Today, however, some three years after that contest, critics have condemned her for, among other offenses, sacrificing the stateless Rohingyas, backsliding on press freedom, failing to forge a peace with militant groups and believing she can bring the generals around on all of the above. "The reality is, Suu Kyi was great as a democracy icon working from the outside," says Anthony Davis, a Bangkok-based analyst with Jane's, a British company that provides military, defense and national security intelligence. "She made the mistake of getting into power. She's become a fig leaf for and hostage of the military."

Not that the generals are happy with any cover she's provided. "She has not lived up to her side of the bargain and has failed to protect the army from Western pressure," says a retired senior officer with links to the commander in chief, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. (Like others interviewed for this story, he asked for anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter. Neither Suu Kyi nor her office responded to requests for comment.)

Suu Kyi's fall has been precipitous. But many say she is a victim of high expectations from those who always saw her as a cross between Mother Teresa and Joan of Arc. "I'm just a politician," she protested in an interview with the BBC last year. After she won the election, she went from an outsider-activist to the ultimate political insider—but one who is trapped between two parallel governments. Ostensibly the head of Myanmar, she is constrained by the country's powerful military, which remains in charge by constitutional mandate. Her party hasn't demonstrated great skill at governing or maneuvering around the cunning generals, analysts say. And many believe Suu Kyi has been paralyzed by her cautiousness and need for control; she has failed to ameliorate the Rohingya crisis because she's too wary of the nativist majority's deep hostility toward the Muslim group. "She's a nationalist," says Khin Zaw Win, a former political prisoner who now directs Yangon's Tampadipa Institute, a public advocacy think tank. "Many Burmese detest the Rohingyas, and she's among them."

Three years ago, when Suu Kyi romped to victory, her followers were euphoric but also aware of the obstacles ahead. Yes, the military had allowed the results to stand—but it did so knowing it would retain most of the power. In 2008, the generals rammed through a new constitution that reserves for the military 25 percent of the parliament's seats, along with control of key ministries: Defense, Border Control and Domestic Affairs. The last one put the military in charge of a sprawling bureaucracy that collects taxes and registers everything from land purchases to deaths. Such powers left it with extraordinary access to citizens' personal and business information, as well as the levers of the country's wealth.

The armed forces also inserted a clause in the constitution barring from the presidency any person with family members who are foreign citizens. Critics maintain this provision was expressly aimed at thwarting Suu Kyi, who not only was married to Aris but had two sons with him who are British subjects. When the NLD won, Suu Kyi adopted the state counselor title because the constitution barred her from being named president. ("The principles in the 2008 constitution are the best safeguard for the country's continued peace and stability," insists the retired military officer.)

Today, Suu Kyi's defenders blame that constitution for preventing her from stopping the forced expulsion, maiming, rape and killing of Rohingyas in Rakhine state. The military's crackdown on the Muslim group started in the 1970s. The latest crisis began last August, and since then, some 700,000 of the country's approximately 1.1 million Rohingyas have fled to Bangladesh. The United Nations and human rights organizations say the military carried out a pogrom, torching the villages of fleeing Rohingyas. Suu Kyi supporters point out, accurately, that she has no control over the generals. The military operates independently, even setting its own budget, which in 2017 totaled $2.14 billion, almost 14 percent of state expenditures.

Cynics allege that the military brass wants to sabotage any attempt to reach a deal with the country's ethnic groups, least of all the despised Rohingyas. "She [Suu Kyi] talks peace and reconciliation, and the military launches more offensives in ethnic areas," says Zin Linn, a media consultant who served two separate jail terms as a political prisoner.

The generals do want peace, the retired officer tells Newsweek, "but we will not surrender power or territory to the ethnic armies." Either way, in early April, fresh fighting erupted between the military and the Kachin Independence Army, a militia that fields 8,000 fighters, according to Jane's. So far, the violence has driven more than 6,000 Kachins from their homes in Myanmar's northernmost state,

located just south of China. "The truth is, Daw Suu did not want another bloodbath in this country," Zin Linn says, using the Burmese honorific for an older woman or one in a senior position. "She wants unity.... That's why she's been so cautious."

Perhaps, but Suu Kyi not only has declined to condemn anti-Rohingya atrocities; she never actually uses the word Rohingyas, which some say underscores her reluctance to recognize them as a separate group entitled to their rights. And critics say she has minimized what the U.N. has called "acts of genocide" and a "textbook case of ethnic cleansing." Last September, in her first comments about the crisis, Suu Kyi blamed "fake news" for exacerbating Muslim-related tensions, citing a "huge iceberg of misinformation." In March 2017, her office dismissed allegations of sexual assault on Rohingya women by Burmese soldiers as "fake rape."

"They're saying, 'Where is the evidence of rape?'" says the Tampadipa Institute's Khin Zaw Win. "Well, the evidence is all on the people there [in Rakhine], especially on the women. If DNA tests were performed, that would be the evidence. For Aung San Suu Kyi to say 'Show me the evidence' is not enough."

Others go further in criticizing the Lady. "The military commits crimes against humanity against the Rohingya," says Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch's Asia Division. "And then, inexplicably, she goes out to defend their cover-up."

Yet publicly supporting Rohingyas and other ethnic groups is not a winning political strategy. Myanmar has no reliable polling, but analysts say an overwhelming majority of Buddhist Burmans loathe the Rohingyas, whom they consider foreigners and call "Bengalis." Brought in from what is now Bangladesh by the British colonizers to work, they remain stateless, with no rights in the country they immigrated to roughly two centuries ago. For decades, the junta tried to strengthen the power of the Burman majority by giving it dominion over all other ethnic groups. "They [the military] try to ensure Burman supremacy. It's partly intentional and partly incompetence on the part of the authorities," says Dr. Ma Thida, a surgeon, writer, activist, former Suu Kyi aide and erstwhile political prisoner.

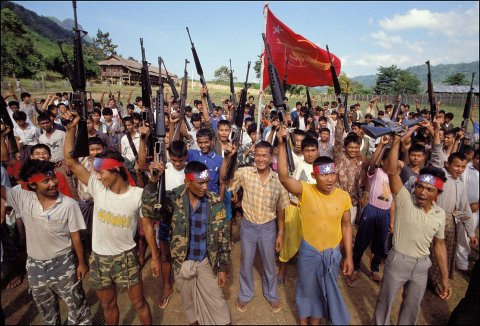

The military recognizes 135 ethnic groups, which make up 25 percent of the nation's 54 million people; Burmans, or Bamars, make up 75 percent. The biggest minority groups include the Shan, Karen (or Kayin), Rakhine, Kachin and Chin. Burmans have preyed on these groups for generations, most recently under the auspices of military strongmen. Many resorted to resistance, spawning the 21 "ethnic armed organizations" now operating in the country. Since 2012, the military and its quasi-civilian governments—and now the governing administration—have pushed for a cease-fire agreement to achieve a national reconciliation, end hostilities and defang the armed groups. "A deal can only be worked out if the ethnic groups sign the cease-fire agreement," says the retired officer. But those organizations demand autonomy in their regions; the cease-fire deal does not resolve that issue, so fewer than half of the groups have signed on.

In 2015, numerous ethnic voters backed the NLD, seduced, like everyone else, by Suu Kyi. "The Chins did not vote for the NLD; they voted for her," says Cheery Zahau, a political activist and country director for the Project 2049 Institute, a U.S.-based think tank. "Ordinary people thought Aung San Suu Kyi would come and feed them food herself." Cheery should know: She ran for parliament in impoverished Chin state and lost to the candidate from Suu Kyi's party. "Now, many realize Suu Kyi won't save them," she says. "Chin people have to save themselves."

Kachins seem to have experienced a similar epiphany in their state, especially after the military's April attacks, the latest outburst in off-and-on fighting dating back to 2011, when a 17-year-old cease-fire fell apart. The state government, run by Suu Kyi's party, approved camps and authorized rescue operations for those displaced by the conflict. But Myanmar's army has blocked such efforts, apparently to mask the extent of the upheaval.

It was another case of the nation's "two governments" in inaction. "We have two entities working separately," the Reverend Hkalam Samson, general secretary of the Kachin Baptist Convention, says in a phone call from Myitkyina, a Kachin city awash in anti-military protests. Roughly half of the state's approximately 800,000 residents are Baptists, and the evangelical group provides assistance to villagers and displaced people. "We are very confused on Aung San Suu Kyi," the reverend says. "She's not focused on ethnic issues. She's focused on democracy and dealing with the Western governments. That's why people are disappointed in her. She's too close to the military."

That disappointment is unlikely to abate as military operations against ethnic groups continue to escalate. In mid-May, at least 19 people were killed in Shan state, when the military battled the Ta'ang National Liberation Army, an insurgent group known for its operations against opium cultivation, near the border with China. Hkalam Samson says Suu Kyi's peace strategy has foundered.

After years of flinging rhetorical bombs at the generals, Suu Kyi maintains an uneasy relationship with them. She says privately that "there's no relationship, no communication" between her and General Min Aung Hlaing, according to someone who knows her. She tried to cozy up to the general after the election, but the violence in Rakhine ended that effort. The leaders of the "two governments" have tussled ever since, says a second person who knows Suu Kyi. But in the spirit of realpolitik, the Lady has eschewed condemnation and confrontation with the military. The second person close to her says she acknowledges in private that the army engages in ethnic cleansing in Rakhine—but she'd never use anything close to that language in public.

Suu Kyi's critics acknowledge her constitutional limitations but argue that she missed an opportunity to leverage her popularity right after the 2015 election. "She had massive international support—including China—and massive domestic support," says Davis, the Jane's analyst. "That would have been the time for a smart politician to push for constitutional change. The military probably would have blinked. She could have had half a million Burmese in the streets of Rangoon in a half an hour."

Maybe, but the military rarely has hesitated to kill thousands. Bo Bo Oo, an NLD member of parliament, says Suu Kyi and the civilian government opted to take "an evolutionary approach" of nonviolence and "no people in the streets." He stipulates that the generals are in charge, so "we have to choose another way"—apparently to speak softly and carry a small stick. Asked to identify some of Suu Kyi's accomplishments in the past two years, the lawmaker acknowledges that "the very rigid constitution is difficult to change," then lists tax reform—"tax income is quite increased"—and improvements in education and health care. If that sounds meager, it is, says Khin Zaw Win, the former political prisoner. You could credit the government with simplifying regulations to boost investment, and for proposals to improve the country's infrastructure. But it's still not much, he notes. Mostly, government officials have thrown rhetoric at tough policy issues, as if they can talk the nation's problems out of existence.

Kyaw Kyaw Hlaing, chairman of Smart, a group of oil and gas companies, says the government appoints officials not for their skills or zeal for certain portfolios but connections to Suu Kyi. "Everything is getting bottlenecked," he says. "Nobody wants to make a decision. Everything has to go to Daw Suu or a minister…who sends it to her." Pantomiming frantic officials waving their hands in the air, he parodies the bureaucrats: "'What does the Lady want? What would the Lady do?'" He adds, "They're not scared of her; they're scared of losing their positions."

It doesn't help that Suu Kyi employs an imperious management style, some analysts say. Even before the NLD won the 2015 election, she announced that while the constitution bars her from becoming president, she would be "above the president." Indeed, the civilian president—first Htin Kyaw, who resigned in March, and now Win Myint—has functioned mostly as a conduit for Suu Kyi. The Lady is also foreign minister. "She has a personalized and centralized form of government, and all the ministers are deathly afraid of her and don't dare criticize her," says Khin Zaw Win. "This centralized system could work if Suu Kyi were more decisive, critics say. But as Smart's Kyaw Kyaw Hlaing puts it, "She's too focused on consequences in making decisions."

Such dithering could harm Suu Kyi's 2020 election prospects, analysts say. "She had better hope that the Burmese people focus on her legendary past rather than what she's accomplished in power when they go to the polls again in 2020," Human Rights Watch's Robertson tells Newsweek. But the Lady intends to win, even if she can't tout many achievements. Bo Bo Oo, the NLD lawmaker, insists that voters are less focused on big-picture issues, such as federalism and peace, and more concerned about improving electricity and garbage collection, creating new parking lots and dog shelters. "Issue by issue, I try to solve," he says. "And they still believe the NLD is the best party to address such issues."

He may be right. The NLD remains popular, and voters don't have a lot of choices. The best alternative is the military, through its Union Solidarity and Development Party. Some say the generals are content to leave governing to the civilians and instead focus on strengthening the armed forces and making money. Others say Aung Hlaing could seriously challenge Suu Kyi in 2020.

Would he run? There are some indications—he's made public appearances and is now using social media. The armed forces normally repulse Myanmar's democracy-supporting populace, but the general is gaining some traction among Buddhist Burmans because he has brutally cracked down on Rohingyas and other ethnic groups. Some Burmans even see him as a defender of the faith.

Conveniently, having allowed Suu Kyi and her party to take over most ministries, he gets to blame her for policy failures and can also use her as a shield against international grumbling about the country not being democratic. "For Min Aung Hlaing, military...support would be reinforced by a genuine popularity among many Burmans as a capable, strong leader…who has travelled abroad extensively while projecting himself at home as the defender of a Buddhist nation which sees itself as increasingly embattled," Jane's Davis wrote.

But the extent of the general's popularity is debatable. Despite his public support, some of his own colleagues are suspicious of his ambitions. "There are many in the military who find this distasteful," says the retired officer. "Many junior officers believe he is more interested in personal power and wealth than the interests of the country."

If Suu Kyi were to be outmaneuvered by Min Aung Hlaing, the armed forces could take total control of the country. "What the military had always thirsted for was legitimacy," says Ma Thida. "With the 2008 constitution and then the election, they got it. That's why there will never be another military coup. They don't need a coup." They would have even less need for a coup if they were to triumph at the ballot box.

Suu Kyi, whose halo may never have quite fit, seems determined to avoid such an outcome. Her unwillingness to confront the military on the

Rohingya crisis, or to get too far ahead of the generals on the peace process, underscores her recognition of the political stakes, says Khin Zaw Win. So does her apparent lack of effort in freeing two Reuters reporters who have been jailed in Myanmar since last December, when they were investigating the killing of 10 Rohingya in Rakhine state. And so does Suu Kyi's mistrust of a free press, exemplified by a paucity of interviews and occasional instructions to underlings to not talk to reporters.

Even now, however, her disappointed backers declare their allegiance while they also vent their frustration. Hkalam Samson, the Kachin leader, is one of them. "We know she alone cannot move this monster," he tells Newsweek. "That's why we pray for her. We still love her."

With reporting by Larry Jagan.