Three years ago, Selahattin Demirtaş was celebrating a political revolution in Turkey.

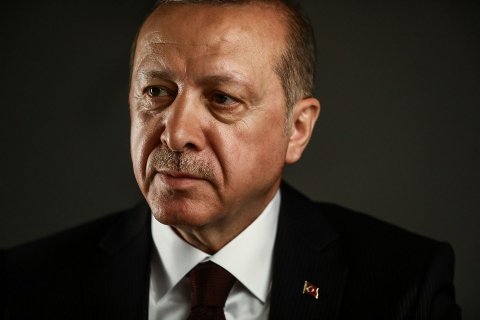

Alarmed by the increasingly autocratic rule of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the Kurdish former human rights lawyer had formed a new political party—the People's Democratic Party, or HDP—and led it to victory in a historic election. For the first time, the country's long-suppressed Kurdish minority was poised to take seats in Parliament, depriving the divisive president's party of a majority and curbing his plans to expand his executive powers. "As of this hour, the debate about the presidency, the debate about dictatorship, is over," Demirtaş declared on election night in June 2015. "Turkey narrowly averted a disaster."

The victory was short-lived. Erdogan challenged the results, and five months later he regained his parliamentary majority in a snap election. Violence swept the country, with Kurdish militants and Turkish forces resuming a long-running war. After surviving a failed coup in 2016, Erdogan ordered a widespread crackdown on opposition groups. Demirtaş and nine other HDP leaders found themselves behind bars, branded as terrorists. Among the dozens of charges heaped on him: insulting the president.

Now, the 45-year-old Demirtaş is mounting a comeback, albeit from his two-man cell in Edirne Prison. On June 24, he will challenge Erdogan for the presidency. The centerpiece of his campaign: his own imprisonment. Holding a political figure for 14 months for making disparaging remarks, Demirtaş argues, is evidence of how Erdogan has replaced democracy with a repressive one-party state. Over the past year, prosecutors have added dozens of charges, for a total of 142 years in jail.

"It is not entirely accurate to call this process a trial," Demirtaş tells Newsweek in answers to written questions passed on by his legal team. "I am being held as a political hostage." (Requests for a response from Erdogan went unanswered.)

As leader of a primarily Kurdish party, Demirtaş has little chance of defeating Erdogan in a country where Kurds make up just 25 percent of the population. But Demirtaş is no token challenger: In June 2015, the HDP won votes outside its Kurdish heartlands by championing the rights of women and minorities, helping deprive Erdogan of a majority. And Erdogan and his fellow nationalists fear a repeat, with Demirtaş winning just enough votes to deny the 50 percent the president needs to win. In that scenario, various opposition groups could then unify against Erdogan in a second round of voting. Dreading comparisons of Demirtaş to Nelson Mandela, nationalist politicians unsuccessfully tried to blunt Demirtaş's popularity by calling for his release. "He showed his ability on a rhetorical level to struggle with Erdogan in a way other opposition leaders have failed to," says Ege Seçkin, a research analyst at IHS Markit.

For Erdogan, this election is crucial. Last year, he narrowly won a constitutional referendum that gives the Turkish president sweeping new powers—establishing a so-called executive presidency that abolishes the post of prime minister and gives the president the power to hire and fire Cabinet members, judges and civil servants. But Erdogan has to win re-election to assume the position he designed.

While he retains significant support with conservative and religious Turks, his overall popularity appears to be slipping. By Erdogan's order, the country has been living under a state of emergency for two years, a period in which tens of thousands of journalists, teachers and civil servants have been dismissed from their jobs and jailed. The president claims that these "terrorists" are linked either to Fethullah Gülen, a U.S.-based cleric whom he accuses of orchestrating Turkey's violent 2016 coup, or the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), the militant group—deemed a terrorist organization by the U.S.—that has waged a bloody, decades-long war for self-rule.

Amid the political upheaval, a steep decline in the Turkish lira is also sparking fears of an economic crash. Facing approval ratings below 50 percent for the first time, Erdogan hastily called elections for June—nearly a year and a half earlier than scheduled.

"Although it seems there are no serious issues arising, as the president and the government are working in harmony, the diseases of the old system can confront us at every step," Erdogan said in announcing the speedy election. "For our country to make decisions about the future…and apply them, passing to the new governmental system becomes urgent."

Publicly, Demirtaş is optimistic about his chances—"I expect to win, naturally," he says—and it is fair to say that his incarceration, although uncomfortable, has been a boon. For Kurds sympathetic to the struggle against the Turkish state, doing jail time for the cause is a badge of honor—particularly when the politician has been incarcerated for making a speech, even having a sense of humor. (In 2015, Demirtaş joked that Erdogan had "fluttered from corridor to corridor" trying to get a photo with Vladimir Putin at a conference.)

But the political calculus makes victory nearly impossible: Neither he nor the HDP has been invited to join the anti-Erdogan coalition headed by Turkey's largest opposition party, the Republican People's Party (CHP). And the HDP's Kurdish roots make the party a tough sell for many, including religious Kurds, who associate Kurdish politics with the PKK.

The ties have been particularly problematic for Demirtaş, whose brother, Nurettin, is a PKK member currently in exile in Iraq. While Demirtaş has defended his brother, the link has proved useful for Erdogan, who has argued that the HDP—or any mainstream Kurdish political party—is a front for the PKK.

Demirtaş, however, blames Erdogan for inflaming the conflict since 2015, when the cease-fire between Ankara and the PKK broke down. If he was elected, he argues, the HDP could end the conflict between the PKK and the Turkish state within six months. "The Kurdish issue in Turkey should be solved by nonviolent means, by opening a channel of peaceful dialogue, by political means," he says. "I believe the PKK will take [the] decision to disarm.… If we come to power, we would be able to solve this problem."

For now, Demirtaş's campaign continues quietly—with an audience of one: his cellmate, HDP parliamentarian Abdullah Zeydan, sentenced to eight years on terrorism charges in May. The pair are kept apart from other prisoners. Each week, Demirtaş is allowed one hour with his wife and two young daughters, and four hours of exercise. He also receives letters, reads international newspapers and watches TV. As such, he has followed the rise of Donald Trump, which has taken place during his imprisonment. ("We feel you have broken the heart of the first lady," he says of the U.S. president. "Please make amends with her.")

As the election approaches, Demirtaş says the guards treat him within the law. "Despite everything, we are strong, our morale is high," he says. "We have lost nothing of our determination in struggle. We believe justice will be done."