Thunder rolls over the cemetery. As Johnny and his sister walk through a graveyard, he taunts her with the now-famous line: "They're coming to get you, Barbra!" A strange man in a tattered suit is walking toward them. He comes awkwardly close, his expression vacant. Barbra bows her head and starts to walk away—and then he grabs her.

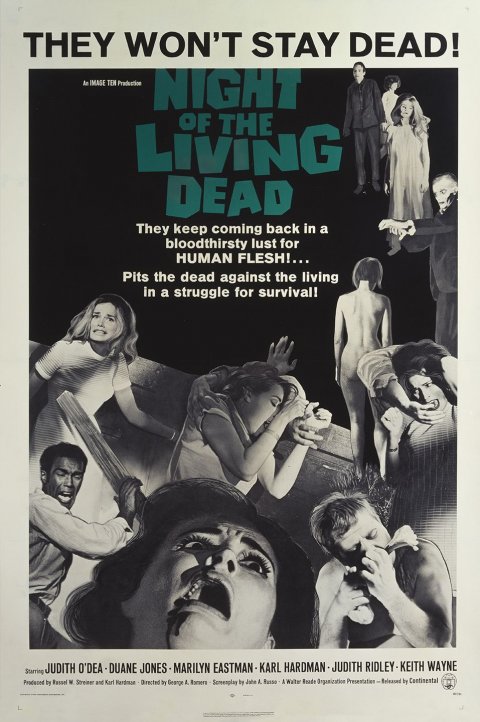

Who is this man? What is the nature of this attack? In 2018, the answers are obvious: He is the undead, and he craves the flesh of the living. But when Night of the Living Dead premiered at the Fulton Theater in Pittsburgh on October 1, 1968, there was no precedent. Zombies, at least as we know them today, had yet to be invented.

That task fell to George Romero, a 27-year-old film buff from the Bronx, and his college friend Russell Streiner. In the early 1960s, they started a commercial production firm, Latent Image, to do local beer commercials in Pittsburgh but soon landed big corporate clients; they shot "Mr. Rogers Gets a Tonsillectomy" and other segments for Mister Rogers' Neighborhood. What they really wanted to do, though, was make a movie.

In 1967, John Russo joined Romero and other Latent Image regulars for some brainstorming. "We would sit around, drinking wine and smoking dope probably, and someone came up with this idea about teenagers from outer space," Russo tells Newsweek. On a $114,000 budget, however, a horror movie seemed more practical. Romero wrote a few dozen pages of screenplay, which Russo used to work up a full draft. Monster Flick, as they called it, starred flesh-eating "ghouls," usually referred to in the script as simply "them."

The characteristics of what we now call zombies (the word is never spoken in Night of the Living Dead) were fleshed out (so to speak) only after filming began in June in Evans City, Pennsylvania, 30 miles north of Pittsburgh. On set, the actors would rehearse, for Romero's approval, the zombie's characteristic limping, dragging, stumbling shuffle. To come up with the hundreds of ghouls that besieged survivors in a farmhouse, much of the skeleton production crew had to double as actors, sometimes in multiple roles, supplemented by a roster of extras.

Russo himself played a zombie killed with a tire iron by Ben, a cool-headed truck driver who clashes with other survivors for control of the farmhouse's only rifle. "I would stretch my face out of shape as much as I could," Russo says, to mimic the effects of rigor mortis. "It gave me a headache after a while."

Even though the team had only one precious jar of 3M stage blood (stretched by also using chocolate syrup, which reads as blood on black-and-white film), they left no stone unturned in search of good gore. For a zombie feast, they used sheep organs, filled with water for a more lifelike flop and squish. Makeup artists Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman (who played doomed mother Helen Coope) added hollowed-out eyes and skin mottled or scarred with mortician's Derma Wax, pioneering a look that special effects artists like Tom Savini would refine for sequels Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead. Mannequin arms, Silly Putty for chewed flesh and exploding blood packets, or squibs, rounded out the gruesome repertoire.

Russo even lit himself on fire for a scene involving Molotov cocktails."Whatever it took is what we were going to do to get that movie made," he says.

Night of the Living Dead was an instant hit, packing drive-ins and defying horrified critics, like the Variety review bemoaning the "pornography of violence" that threatened the "moral health of filmgoers who cheerfully opt for this unrelieved orgy of sadism."

The movie came to be regarded as a critique on 1960s American society. Black actor Duane Jones, cast as Ben, takes charge amid the zombie siege. He survives the long night (spoiler alert!) only to be shot the next day by gun-happy hicks and police.

Romero and Russo didn't originally intend to create a racial subtext, but they were aware that they had—especially after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April of 1968. Romero recalls hearing the news on the radio while driving to New York City, in search of a distributor, with the film canisters in the trunk. Jones was concerned with how audiences would react; he argued, unsuccessfully, for more acknowledgment of the underlying racial tension between Ben and the other survivors, particularly Harry Cooper (Hardman), who chafes under Ben's leadership.

Critics interpreted Night of the Living Dead in different ways. Some saw a dark echo of the Vietnam War, others a reactionary backlash of an older generation against the youth movement. In the past 50 years, the film has spawned five sequels, including the consumerist-critiquing Dawn of the Dead and the gore masterpiece Day of the Dead (both by Romero). It invented an entire subgenre of horror that has since inspired hundreds of movies and TV shows, including ongoing hits like The Walking Dead.

At its center is the radical emptiness of the zombie, who lives and dies by specific rules, but has no backstory and no internal motivation beyond ravenous consumption. The simple horror of Night of the Living Dead is the realization that society has gone dreadfully wrong, as frightening a concept today as it was in 1968.