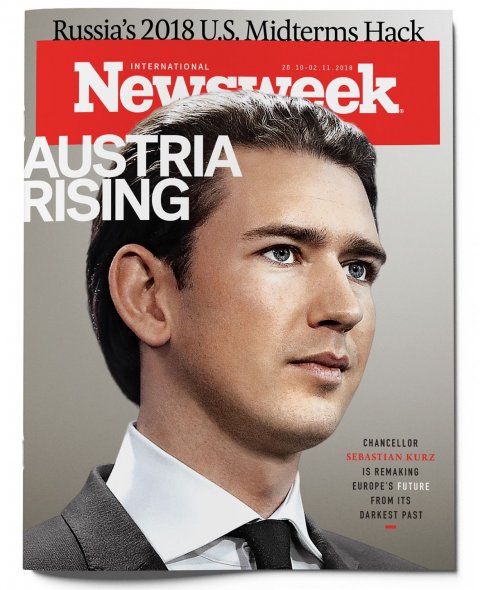

May 2017, when Sebastian Kurz took control of the center-right Austrian People's Party (OVP), he remade it in his image. Lest the world underestimate the significance of this, the 32-year-old rebranded the OVP as the Sebastian Kurz List–New People's Party. Seven months later the conservative populist became Austria's youngest-ever chancellor, in addition to the world's first millennial head of state and, according to some analysts, the future of Europe.

Like other right-wing populists ascending to power in the European Union, the ambitious Kurz has pushed a hard-line immigration agenda in response to economic stagnation and the Syrian refugee crisis. But his youthful persona and political happenstance have elevated his status and his ideas far beyond Austria's borders. His rise coincided with the transition of the EU presidency to Austria, a six-month term, ending in December, that has given him a platform to challenge the liberal order of Europe and its cherished tradition of open borders.

His tenure as EU president is not without controversy. Kurz's official motto, "A Europe that protects," is another way of saying "secure the continent's borders." He has the support of the openly xenophobic Freedom Party of Austria (FPO), as well as far-right leaders Viktor Orbán, Hungary's prime minister, and Matteo Salvini, Italy's deputy prime minister. Together, the three have proposed measures to control Europe's borders, including establishing screening facilities for migrants outside the continent and returning those intercepted at sea to the country from which they came.

For the first time in 100 years, since the end of the Habsburg Empire—when Austria ruled much of Europe for close to 500 years—the country finds itself in a position of power. The economy is growing, and unemployment is down. In September, the neoliberal daily Die Presse praised Kurz's appearance at the United Nations as a show of strength "from the new small superpower." The newspaper lauded what it described as Kurz's "speed dating": meeting with American, Turkish and Israeli leaders and making "major diplomatic successes" in just two days. The most notable achievement was brokering a meeting with Israel for Austria's right-wing foreign minister, Karin Kneissl, who had angered Jews both at home and abroad when she wrote in her 2014 memoir, My Middle East, that Zionism was a violent ideology based in 19th-century German nationalism.

Young Austrians, who don't remember a time when the country was on top, are loving this moment. To many in their 20s and 30s, Kurz's coalition with the FPO—founded by neo-Nazis after World War II—is the price of shaking off the political status quo, as well as decades of centrist grand coalition governments with the OVP and Social Democrats (SPO). In their view, so much political compromise was required that little got done. "A new political style was needed in Austria," says one of Kurz's fans, a 28-year-old interpreter named Julia. "Finally, someone dared to break up outdated party structures. He is not a yes-man, as he showed [to German Chancellor Angela] Merkel during the refugee crisis."

As foreign minister in 2015, when Syrian refugees began streaming into Europe, Kurz suggested closing Austria's border with Italy. Since taking power, Kurz's government has shown it does not feel beholden to European norms; in early October, Vice Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache said at a function in Vienna that he would like to follow the lead of Orbán and U.S. President Donald Trump by withdrawing Austria from the U.N. Global Compact for Migration, which aims to set standards for orderly migration.

But the chancellor's popularity with Austria's youth goes beyond ideology. The selfie-posting, party-rebranding Kurz—often referred to simply as Sebastian by millennials—is one of them. This master marketer understands, perhaps better than any other EU leader, the power of personality-driven politics, social messaging and bullet-point ideology. As Trump's ambassador to Berlin, Richard Grenell, put it in an interview with Breitbart News, Kurz is "a rock star."

Kurz has long been a wunderkind. He grew up an only child in Meidling, a gentrifying neighborhood on the edge of Vienna, and entered politics as a teenager in the OVP's youth organization. He dropped out of law school and in 2010 won a seat on the Vienna City Council. Within a year, he was appointed to the federal government as state secretary for integration of new immigrants. After winning the most direct votes of any candidate in Austria's 2013 legislative election, Kurz was made the world's youngest-ever foreign minister, becoming an integral negotiator in the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran.

In a hip café in Vienna's upscale Leopoldstadt district, a group of economics students clustered around new silver laptops gushed over their slick-haired, baby-faced leader. Among other things, they extolled his ability to speak to them in ways that are inclusive, anti-intellectual and unpatronizing. "He tells people what he's going to do, and then he implements it," says government spokesman Peter Launsky-Tieffenthal. "He takes the public along through the steps, explaining things in terms people can understand."

For example, alongside his 2017 campaign proposals on his website, such as tax cuts for families, he included a projected timeline for implementation and a "program generator" so each citizen can find government services.

While the move is seemingly simple, Kurz's admirers point out the stark contrast to the EU's remaining progressive vanguards, Merkel and France's Emmanuel Macron, who have adopted a more opaque approach to government—one that, along with the migration crisis, is increasingly undermining their popularity. After winning the French election with 66 percent of the vote a year ago, Macron had a 29 percent approval rating in October. That and the departure of seven top ministers in the past few months—many of whom expressed dismay over Macron's inaccessibility—have left his administration in crisis.

In Germany, months of embarrassing spats between Merkel and her Cabinet have damaged her hold on power, leading to a lame-duck fourth term as chancellor; in polls, her conservative party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), is now just 10 points ahead of the radically right-wing AfD. Formed just six years ago, AfD's growth has been explosive; the party had the third-strongest showing in the September 27 elections, with 92 lawmakers in parliament. (Co-leader Frauke Petry once claimed there were situations where German border guards could legitimately shoot refugees trying to get over the border.)

With Macron and Merkel in jeopardy, Kurz sees a chance to fill the void on the world stage. And notably, Austria seems united behind him, regardless of age. "It doesn't make sense to speak of a generational difference in support for the government," says professor Peter Filzmaier, a leading political scientist at Austria's Graz and Krems universities. Additionally, he says, archconservatism and traditional values aren't the purview of baby boomers or the elderly; both score well with young voters here.

The FPO—once considered a junior party—is currently at 24 percent public support, down roughly 2 points since last year's election. That's a strong showing for a country with six major political parties. The party has decried the "Islamization" of the West and made headlines for anti-Semitism scandals. (Many FPO lawmakers are former members of the country's traditional nationalist fraternities; activities include "drinking songs" promoting a continuation of the Holocaust.)

Launsky-Tieffenthal maintains "the FPO has distanced itself from the anti-Semitic past." As proof, he cited Kurz's number two, Strache, the leader of the FPO, expressing sympathy for Israel's push for the EU to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel (bitterly contested by Palestinians, who consider it their capital as well). "This," said Launsky-Tieffenthal, "showed leadership."

Kurz's supporters refer to him as a bridge builder. But he might just be the consummate poker player, adept at flipping back and forth between ultra-conservative and conservative opinions, without alienating the FPO. As the website Foreign Policy explained it, "Austria's chancellor thinks he's cracked the code for neutralizing populists—by cooperating with them."

But liberals like Mattias Strolz, leader of the New Austria and Liberal Forum (NEOS) party, fear the worst, accusing Kurz of "expertly using a putsch to come to power" and eroding parliamentary democracy. "He cut the hair off the old-lady OVP, and everyone was excited."

"This entire republic is drunk on this performance," he said in a speech. "People will wake up with a hangover."

Past Is Prologue

Deep in the Austrian countryside, on church-owned land, Europe's largest annual neo-Nazi convention takes place in the small town of Bleiburg. Here, every May, roughly 10,000 participants from all over the EU swap Hitler salutes. Activities include inflaming tensions with Italy over South Tyrol (formerly an Austrian province and home to thousands of ethnic Austrians) by suggesting Austria take it back and paying homage to Croatia's Ustase army, best known for the only Nazi extermination camp built voluntarily, without German participation.

Austria is also home to the increasingly visible European far-right group Generation Identity, which promotes acts of violence against leftists and refugees, including a 2016 incident at the University of Vienna; members screamed and threw fake blood at refugees performing in a play. GI's ideology—a bizarre web of nationalism, anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and Islamophobia—is often spread using hipster aesthetics and left-leaning tactics; for example, they want to follow Greenpeace's lead and take to the sea—only instead of saving refugees, they would stop rescuers from helping. Their leader, Martin Sellner (whose fiancée is American alt-right YouTuber Brittany Pettibone), scored a major legal victory in July when he was cleared of hate speech charges, prompting the government to rethink relevant statutes: After the verdict, the president of the legislature announced a need to strengthen hate speech laws.

The rise in far-right extremism has effectively fueled Kurz's political career. One of his immigration policies, for example—forcing migrants to hand over valuables and cellphones—has uncomfortable echoes of Nazism. Kurz has also joined Hungary's Orbán in rejecting Germany's proposal of distributing refugees across the EU. Refugee relocation, he has said, "isn't working," and Europe must protect its "Christian culture."

Merkel and Macron are determined to stem the tide of rising populism and come up with a liberal solution to problems of migration policy. Their success will be determined by the European elections in 2019. While the EU may have ostensibly agreed to a bloc-wide immigration policy at a summit at the end of June, concrete details of a future plan were scant, and leaders have shown little sign of implementing any new strategy.

But Kurz has picked his side. Just a few days before the summit in June, he staged provocative army exercises at the border of Slovenia to show he was ready for any migrant-related activity. It was a highly irregular move for a country ostensibly aligned with Germany, a champion of open borders and averse to military action. But Austria's chancellor has hinted at a willingness to break with Berlin. Although his party has strong ties with Merkel's CDU, Kurz has shown a readiness to pivot toward the greatest thorn in the German chancellor's side—her archconservative interior minister, Horst Seehofer.

Seehofer is the former governor of Bavaria, the German state bordering Austria. He prompted the first major crisis of Merkel's new government in June, when he threatened to remove his Christian Social Union (CSU) party, the Bavarian sister of the CDU, from the ruling coalition over immigration. While Kurz was careful not to take sides, his sympathies were clear. He said he was happy that Germany was having a debate about its liberal immigration policies.

Launsky-Tieffenthal, the Austria spokesman, downplays both the importance of the military maneuvers and Kurz's ties with Orbán. "There is no one the chancellor is in contact with more than Merkel. Yes, we have some common ground with Hungary…but the relationship with Orbán isn't so special," he tells Newsweek. "We simply want to be bridge builders" between Eastern and Western Europe.

He says Merkel's handling of the refugee crisis in 2015 "probably encouraged more people to come and made matters more difficult. But Austria has kept 80,000 refugees. That's larger per capita than any other European country after Sweden. France took only 500. After that, we felt a bit abandoned by the others, and that's what provoked the debate about migration we're having now."

Some suggest that Kurz saw Bavaria's key regional elections in October as an opportunity to align German policy with Austria; his recent appearances with officials from Seehofer's conservative CSU were seen by some as tacit endorsements. "He may use the EU presidency and his chancellorship to more strongly align himself with Seehofer and the CSU over Merkel," says Filzmaier.

Waldheim's Shadow

Germany has a key advantage for countering the rise of populism: It has acknowledged and made amends for its Nazi past, and there is an organized and motivated left-wing movement to keep the far right in check. AfD can't hold a political convention without meeting tens of thousands of counterdemonstrators, who frequently outnumber far-right marchers. In one memorable event in Munich last year, roughly 100 extremists were boxed into a central square by thousands of opponents.

In Austria, however, only a smattering of protesters make their way to Bleiburg to demonstrate against the annual neo-Nazi meetings. The reason for this extends to the immediate aftermath of World War II. There was no equivalent of the Nuremberg trials in Austria. Vienna did not begin to question the Nazi leaders remaining in power until 1986, when it was discovered that former U.N. Secretary-General and Austrian President Kurt Waldheim had been an intelligence officer for Nazi Germany's armed forces, the Wehrmacht.

Instead of reckoning with being the birthplace of Adolf Hitler or welcoming the arrival of his troops in Vienna, Austria embraced the opinion of the Allied powers in the late 1940s. "The Allied powers called Austria a victim, and the country obviously accepted that because no one wants to be one of the perpetrating countries," says Filzmaier, who believes the truth is somewhere in the middle. "Germany was forced to accept its violent past and new political education in a way that Austria wasn't." As a result, he adds, "it is historically and geographically unsurprising" that Austria has been home to old and neo-Nazis. "The problem is the lack of sensitivity for this fact."

Launsky-Tieffenthal insists, however, that things are changing in Austria. "It's true that we didn't talk about the Holocaust when I was in school," says the 60-year-old government spokesman, "but after the Waldheim years it became present and since then has been subject of a broad public debate. As part of our curriculum, students visit concentration camps, and, in addition to that, the government supports building a memorial wall of names and plans to offer citizenship to the descendants of Holocaust victims."

Recently, on top of Strache's stated belief that Jerusalem should be the capital of Israel, Kurz has been making overtures to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who, according to The Jerusalem Post, met Kurz in a private art gallery replete with Austrian masters like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele. There, Netanyahu reportedly praised Kurz's new immigration curbs, and the Austrian leader hinted at his desire to hold a conference on Islamic anti-Semitism.

One of those new immigration curbs was introduced by Interior Minister Herbert Kickl of the FPO, alongside his Italian counterpart Salvini, a relationship that has grown noticeably tighter. Together, the pair announced in September a plan to stop ships carrying immigrants before they land in Europe.

"They will be well looked after on the ships," Kickl said of the vessels, notorious for filthy conditions and lack of food and water. Immediately after the meeting, Salvini made it clear that the aim is to stop immigration from Africa and the Middle East at all costs.

New Agenda, Potential Backlash

All signs suggest the Kurz administration is just getting started. The government recently unveiled the dubiously titled initiative "new fairness," a policy that ensures Austrian citizens are "treated fairly." Simply put, natives will be first in line for government benefits, while refugees and migrants may see cuts in support. In addition, integration programs for new migrants, such as workplace apprenticeships, have been scrapped, and access to German lessons has been reduced.

The new system will also distinguish between economic immigrants and those seeking asylum, with a preference for the latter. And there are, apparently, limits: In one case in September, a gay Iraqi refugee had his asylum application rejected because he was "so girlish." The authorities apparently decided he was just pretending to be gay.

Alongside immigration reform are major plans for economic incentives, including rewarding families for having children, as the native-born population is dwindling, and encouraging people to start businesses. According to the government, these are the same priorities they want to focus on for the remainder of Austria's EU presidency.

Amid the changes, left-leaning Austrians, represented politically by the SPO and the Green party, feel outnumbered and paralyzed. A few protests against the FPO last fall quickly dissipated, and many self-identified leftists in Vienna tell Newsweek they "can't think about politics anymore."

"I voted for Sebastian Kurz because of his youth and earlier experience as the youngest foreign minister in the world," says Johannes, a 29-year-old dentist. "Unfortunately, then his party entered into a coalition with the FPO, causing a rightward shift for the chancellor's party and me to regret my vote.… We need a more global way of thinking that goes beyond our border."

Former Austrian Chancellor Kern, whose SPO party was a major supporter of Merkel's open-door refugee policy, has been openly critical of Kurz and his political alliances. He told German daily newspaper Die Welt in August that the FPO "disseminates anti-Semitic conspiracy theories about George Soros. Every week there is a racist, right-wing extremist rally that in a civilized democracy would have led to resignations."

Kern also accused the FPO of "playing Kurz like a fiddle" and condemned the alliances with the ethno-nationalist governments of Italy and Hungary. But those criticisms seem unlikely to translate to political gains; Kern was poised to spearhead a left-wing countermovement to Kurz in next year's elections, but then, to the surprise of his own party, abruptly retired from politics in early October.

Like many in Britain who oppose the looming Brexit, or Americans enraged by the populism of the Trump administration, the feeling among anti-populist Austrians is one of helpless consternation. "I am opposed to the current government because of the FPO's long history of hate speech and incompetence," says Thomas, a young expat living in New York who is disheartened by FPO racism. "Kurz should not enable them but obviously believes he needs to and has at least dabbled in demagoguery himself."

It's been 18 years since the left last staged demonstrations. In 2000, groups would host weekly "Thursday protests" in Vienna to target the FPO's relationship with Nazism. But there are signs that the opposition may be stirring again. On October 4, several left-wing and social activist groups held a rally in front of Kurz's office. According to organizers, some 20,000 people were in attendance. It had the air of an outdoor picnic, but the sentiment was strident. "Bye, Basti!" read one sign, using a nickname for Sebastian. The crowd chanted "Resistance! Resistance!"