It's not easy to get in to see Diane Ellis-Marseglia, one of three commissioners who run Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Security is tight at the Government Administration Building on 55 East Court Street in Doylestown, a three-story brick structure with no windows, where she has an office. It also happens to be where officials retreat on election night to tally the votes recorded on the county's 900 or so voting machines. Guards at the door X-ray bags and scan each visitor with a wand.

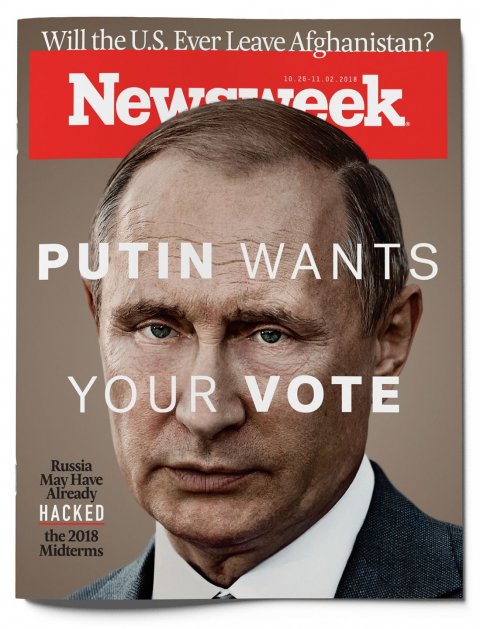

Unfortunately, Russian hackers won't need to come calling on Election Day. Cyberexperts warn that they could use more sophisticated means of changing the outcomes of close races or sowing confusion in an effort to throw the U.S. elections into disrepute. The 2018 midterms offer a compelling target: a patchwork of 3,000 or so county governments that administer elections, often on a shoestring budget, many of them with outdated electronic voting machines vulnerable to manipulation. With Democrats on track to take control of the U.S. House of Representatives and perhaps even the Senate, the political stakes are high.

Russian hackers were notoriously active in the 2016 election. Although President Donald Trump disputes it, evidence suggests that they were responsible for breaking into the Democratic National Committee's computers, according to U.S. intelligence reports. They ran a disinformation campaign on Facebook and Twitter. They also attacked voter registration databases in 21 states, election management systems in 39 states and at least one election software vendor—and that's only what the government's intelligence services know about.

Although there's no evidence that these attacks resulted in direct changes in vote tallies, cybersecurity experts fear that the Russians may have already made inroads into the U.S. election system, including planting malware—malicious computer programs—in the voting machines themselves. States and counties have reacted so slowly to the threat that secure voting machines aren't going to be in place until 2020, giving the Russians an incentive to strike in 2018, while they can.

The result could be a historic foreign attack on the very mechanics of U.S. democracy, says David Hickton, a former U.S. attorney who focuses on cybercrime. "This is an assault on our sovereignty. Russia's hacking architecture is already in place here. The only question now is, What are we going to do about it?" Early in October,

Hillary Clinton compared Russia's cyberinfluence on our elections to the events of 9/11. "We have been attacked by a foreign power," she says, "and have done nothing."

The U.S. certainly hasn't forced the Russians to look hard for places to strike. The midterm elections are rich in targets. Bucks County is hardly unique in relying on easily hacked voting machines, whose results could determine control of Congress or individual states. About 30 percent of America's voting machines are as outdated and nearly unprotected as those in Bucks County, says Marian Schneider, a former Pennsylvania deputy secretary for elections and administration and now president of Verified Voting, a national election-integrity advocacy group. Ballotpedia, a nonprofit website that tracks elections, lists nearly 400 congressional and top state official races this November as competitive enough to be considered battleground contests.

Bucks County is typical, in many ways, of the districts that hackers would likely target. For one thing, it's a swing district in a swing state. In 2016, Trump edged out Hillary Clinton in Pennsylvania by about 45,000 votes—less than 1 percent. Just last March, Democrat Conor Lamb beat Rick Saccone by fewer than 800 votes in a special election for a House seat in the state's 18th District, near Pittsburgh. Races in districts next to Bucks County's have been decided by as few as tens of votes, and more than once. Some local elections in the county have ended in ties.

The midterms in Bucks County will be close. Bucks makes up most of Pennsylvania's 1st District, where Republican Brian Fitzpatrick faces off against Democrat Scott Wallace in a race for U.S. representative. Because district lines were recently redrawn to comply with a court order, neither candidate is an incumbent. Polls suggest the contest may well be settled by just hundreds of votes.

Another reason Bucks may be a target is its voting technology. The county relies on the Shouptronic 1242, an electronic voting machine designed in 1984, before hacker referred to a malicious computer programmer. A Shouptronic looks like an ancient desktop PC blown up to the size of a refrigerator, with push buttons instead of a display screen. When a citizen goes behind the curtain and hits the "vote" button, the Shouptronic stores the result electronically on what is essentially a 1980s-vintage video-game cartridge. After the polls close, officials go around to the 900 or so Shouptronics machines set up in churches, schools and other polling places around the county, gather all the cartridges and bring them to 55 East Court Street. There, behind the sturdy brick walls, they load the cartridges, one by one, into a reader, which tallies the vote.

Making sure each vote gets counted is a big part of Ellis-Marseglia's job. She is aware of the threat from Russian hackers, but she seems confident that residents' votes will be safe. "I do worry about the safety of the election overall in the U.S.," she says. "But not here. There's no reason for concern with any of our machines. Our machines aren't connected to the internet, so I don't see the problem."

The county's chief information officer, Don Jacobs, a former IT executive in the real estate industry, also stresses the lack of a direct online connection to the voting machines. "The vote count is on a cartridge that's manually carried to a reader, and that reader isn't connected to the internet either," he says. "It's a secure system."

But cybersecurity experts say this confidence is misplaced. "Are you kidding me?" says Hickton, who co-chairs the Blue Ribbon Commission on Pennsylvania's Election Security and directs the University of Pittsburgh's Institute for Cyber Law, Policy, and Security. "You can't bury your head in the sand and say these machines are safe because you lock them in a closet before the election. Anyone who says that lacks understanding of the cyberthreats."

How to Hack an Election

Even though Bucks County's Shouptronics aren't wired, hackers have several ways of compromising them. The most direct and effective way would be to replace a computer chip in the machine that holds instructions on what to do when voters press the buttons with one that holds instructions written by hackers. When this chip is working properly, it ensures that a voter who presses the button next to Mary Smith's name actually registers a vote for Mary Smith. A hacked chip could be programmed to add that vote to the rival's tally instead. Or, to avoid detection, it might switch only one in five votes for Mary Smith to her rival.

Or it could simply fail to register a vote for either candidate. This technique is called "undervoting," because it implies that the voter chose to not vote for either candidate, which voters sometimes do. To further avoid pre- and post-election tests, the hacked chip could be programmed to behave perfectly correctly for an hour or so on election morning, when pre-election testing is typically done, and also to stop misbehaving just before voting ends, so post-election testing won't turn anything up.

Swapping a chip would require physical access to the machines, either sometime before November 6 or on Election Day itself. Andrew Appel, a Princeton computer science professor and leading expert on election cybersecurity, once publicly demonstrated how. Armed with a screwdriver, some lock-picking tools and a few fake seals, he opened a panel on the machine and swapped out the chips. It took him seven minutes. Russian agents could conceivably bribe any of hundreds of local election officials, employees or contractors who have access to voting machines at some point to perform this task.

The Shouptronics can also be attacked online—no physical access needed. Such a hack would target the software that labels the voting buttons. Voters make their selections on the machine by pressing rectangles on a poster-sized printed ballot mounted over the machine's front panel. Pushing on the rectangle in turn activates physical buttons on the machine itself, which register the vote. For each election, officials program the machine to match the appropriate rectangles on the poster to the buttons on the machine. If there's a mismatch, the vote won't be counted properly.

The program that maps the buttons to the printed poster is a computer file that's entered into the machine just before the election via another one of those 1980s video game–style cartridges. That file is created on the computer of a county official or employee, or that of a contractor. That computer is almost certainly connected to the internet, and it would almost certainly be hackable. And therein lies the vulnerability.

Getting into the button-programming file would require lifting the password of almost any employee in the organization, often just by trying the easily guessed passwords that many people still use. Hackers can also send a phony but convincing-looking "phishing" email that tricks recipients into giving up their passwords. That's just what happened in Bucks County in September last year: A county employee was reportedly fooled into clicking on an infected attachment by a phishing email that appeared to come from a Pennsylvania state agency. The employee's computer then, on its own, sent the malicious email and attachment to an estimated 700 county officials and employees. The county claimed the problem was contained, but there's no way to be sure what information or software may have been compromised.

Alternatively, a hacker could get to the computer of anyone involved in setting up or printing the ballot poster, altering the PDF file that contains the poster image and shifting one or more rectangles to align with the wrong buttons.

A button-mapping hack could be carried out entirely from Russia. It might simply involve swapping the Shouptronic rectangles corresponding to two opposing candidates on election night, so that a vote for one candidate is counted as a vote for the other. That would be an ideal hack in a race where the hacker's favored candidate is expected to narrowly lose; the machine would fraudulently report that the candidate had narrowly won. And in a close race, there'd be little cause to insist there was foul play—and absolutely no way to do a recount to be sure.

Russian hackers have already had documented success in penetrating the computers of dozens of state voter-registration databases and election management systems, the Democratic National Committee and the country's electric power grid. Compared with these feats, a button-mapping hack would be a cinch.

Pre-voting testing by an official or monitor at the polling place could theoretically catch a button-mapping hack in progress. Unfortunately, such testing isn't always carried out thoroughly, or at all. For instance, no one noticed when buttons for two candidates in a 2011 New Jersey primary election, for two seats on the Cumberland County Democratic Executive Committee, were switched. According to Appel, who was consulted after that election, the only reason the swap was noticed at all was that the candidate who had expected to win by a landslide actually lost by a landslide. Only after the "losing" candidate obtained an overwhelming number of affidavits from voters was the discrepancy found out. Was it a hack or an honest mistake? With the Shouptronic, there's no way to know, because it doesn't leave a paper trail that can be checked after the fact.

"If the only way we can trust an election is by getting affidavits from every voter, we're in trouble," says Appel.

It's possible the Russians perfected their attacks on electronic voting machines in the 2016 election without tipping their hand. No such attacks have been documented—but then again, nobody's looked. "As far as I know, exactly zero machines were forensically tested after the elections," says cybersecurity expert Alex Halderman, a computer science and engineering professor at the University of Michigan. In other words, we have no way of knowing if voting machines in Bucks County and other vulnerable counties with tight races for House seats are already primed to report phony results ordered up by Russian intelligence officers.

Paper Trail

What makes the Shouptronic and other "direct-recording electronic" machines potentially destructive is that they do not accept or produce paper ballots or any other paper record of individual votes. Pennsylvania, along with Louisiana, Georgia, New Jersey and South Carolina, rely heavily on DRE machines statewide. DRE machines have been entirely done away with in 39 states, and most of the other states have largely replaced them. In a paper-based machine, a voter either fills out a paper ballot (which is then inserted into the machine for optical scanning) or else votes electronically on the machine and then looks at a paper record printed by the machine to confirm that the votes were properly recorded. The paper ballots or printed records are saved.

The security advantage of paper-based machines is that they leave a paper trail that can be examined to turn up discrepancies with the electronic tally and, if necessary, to enable a full recount of paper ballots to replace the electronic tally. No one knows how to hack a pile of paper ballots under the noses of election officials. That's why New Hampshire, which has close races for House seats in November, is a far less likely hacking target. "Eighty-five percent of the ballots cast in New Hampshire are counted by optical scanners, and the rest are counted by hand," says David Scanlan, New Hampshire's deputy secretary of state. "We do more recounts than any other state."

Without paper ballots to recount, there's no good way of knowing how many times DRE machines have miscounted elections in the past, either through hacks or errors. Officials watch for underreporting of votes—when machines report unusually large numbers of incomplete ballots, which suggest the machines have been discarding votes. Shouptronic and similar DRE machines have been involved in more such "undervoting" incidents than any other type of voting system. In the 2004 presidential election, nearly half the ballots recorded by Shouptronic machines in some New Mexico precincts showed no vote for any presidential candidate, compared with a few percent in precincts that used other machines. Georgia's DRE machines have had numerous crashes, glitches and suspicious results since their installation in 2002. As the machines have sunk further into obsolescence since the early 2000s, the risks have risen, says Hickton.

Bucks County knew about these risks when it bought its Shouptronic machines in 2006. "We were extremely involved in the process, and we advocated for paper ballots," says Peggy Dator, co-president of the Bucks County League of Women Voters, one of several groups that opposed the county officials' decision. Not only do the Shouptronics fail to provide a paper record, but the county bought them used—which means they could have been hacked on arrival.

"Buying those machines was a remarkably bad decision," says Halderman. "The Shouptronics were already ancient at that point. It's astounding they're still in place today."

Bucks County residents seem mostly oblivious to the dangers. At Nonno's Cafe, nestled in a charming warren of artisan shops in downtown Doylestown, Mary Rose Bocchino, the petite, animated owner of the shop, pulls a double espresso as she dismissed security concerns about the upcoming elections. "I trust that people have been working on protecting against hackers," says Bocchino, who intends to vote Republican. "I'm more worried about people not having to show an ID to vote."

Beyond 2018

Under pressure from the federal government, along with $380 million in federal funding, Pennsylvania and the 10 other states that still rely on DRE voting machines are working to replace them with paper-ballot-based machines in time for the 2020 primaries. But those machines won't be available this year.

Safe-election advocates in Georgia, which relies entirely on DRE machines, sued in federal court this year to force the state to replace them with paper machines for the midterms. The ruling in September excoriated Georgia officials for not having moved earlier to get rid of the DREs but conceded there wasn't enough time to do it by November. As a result, the Russians are unlikely to get a better shot at hacking enough votes to swing a key election than they are this November. Russia is looking at a wide-open window that's going to start rapidly closing next year.

That doesn't mean we'll be in the clear in 2020. Getting rid of all the DREs will give every county in the U.S. the ability to conduct trustworthy recounts of paper ballots where there's reason to suspect problems. But will county and state officials be able to tell their elections have been hacked so they can then turn to the paper ballots for a full recount? The only sure way to tell, say experts, is to routinely sample a carefully calculated percentage of the paper ballots—the percentage varies with how close the election is—and compare them with the electronic record.

These so-called "risk-limiting audits" aren't happening yet in most of America, even where there are paper ballot machines that make it easy to do so, and it's not clear that will change much by 2020. "Right now, only a few states have high-quality risk-limiting audits," says Appel. Half of all states don't do any audits.

In 2020, audits will be the next battleground for election security. Although replacing DREs will be removing one kind of vulnerability, others will remain. In a paper-based voting system, the computers that update the machines' software are themselves vulnerable to hacking. If those computers are breached, fake software updates could be distributed to tens of thousands of machines all through the state.

Good luck protecting those computers, says Ryan Lackey, founder of cybersecurity firm ResetSecurity and chief information officer at cryptocurrency company Tezos. "It costs tens of thousands of dollars per computer to fully protect against all security threats," he says. "Election-related computers are bigger targets, and the people protecting them don't have a fraction as much to spend on security."

The irony is that the more election technology advances, the more reliant we'll be on paper ballots to keep Russian and other hands off the levers of our democracy. That leaves us facing the hard fact that in one of the most potentially significant elections this country has ever faced, the machines in Bucks County and hundreds of other counties like it—the machines that are the most likely to make all the difference in who governs America—won't have a single piece of paper between them. For the lack of that paper, we'll probably never know for sure how the elections really turn out.