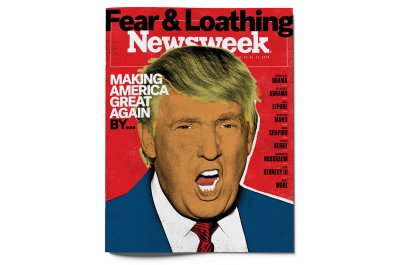

An unseasonable icy cold swept into Washington in mid-December, like a celestial omen that winter was coming for Donald Trump's presidency. With the sentencing of three former key aides, including his personal lawyer Michael Cohen, and the guilty pleas and prosecutorial cooperation agreements of others, the administration seemed suspended between the end of the beginning and the beginning of the end. In guarded conversations on the edges of holiday cocktail parties in the capital's power corridors, Republicans, Democrats and longtime "deep state" bureaucrats seemed to recognize that a turning point had been reached. The end, perhaps, was in sight, if not near.

"I can't imagine he'll escape the traps Robert Mueller has set for him," one top former national security official whispered, speaking of the special counsel investigation on condition of anonymity because he deals with the Trump administration on intelligence issues. "Then there's the New York stuff [investigations of Trump's foundation, the Cohen scandal] and now Democrats coming into power in the House. He's in a very tight spot."

With the various vises tightening, conversations turned toward another icy specter: Would Trump leave the White House if prompted to do so by an indictment or impeachment vote?

The president himself revived jitters over the prospect of going rogue when he predicted in a Reuters interview on December 9 that "the people would revolt" if he were impeached. Earlier in the year, he notoriously crowed approval of Chinese President Xi Jinping's abolition of term limits. "I think it's great," he said. "Maybe we'll give that a shot someday."

Trump's warning of a popular uprising on his behalf drew widespread mocking. "I think he has confused the word 'revolt' with 'rejoice,'" went one typical Twitter comment. But others worried over armed Charlottesville-style mobs descending on the capital, the media outlets Trump calls "enemies of the people" or even synagogues. "There is potential for a lot of street violence," retired three-star Army General Mark Hertling tells Newsweek.

No matter that an impeachment hearing in the House alone seems far off, given the caution of key Democrats on the matter, not to mention Republican control of the Senate. "Many tremble at the idea, fearing how Trump's supporters will react to an impeachment inquiry, worrying that it will further polarize an already deeply divided nation or that there will not be enough votes in the Senate to convict him, even if the House votes to impeach," former New York Representative Elizabeth Holtzman, a member of the House Judiciary Committee that voted to impeach President Richard Nixon, writes in her new book, The Case for Impeaching Trump.

Nixon had similar fantasies of "the people" coming to his rescue as Congress and prosecutors closed in. But as it turned out, the "creature of the establishment," as Watergate chronicler Elizabeth Drew recently described Nixon in The New York Times, bowed to reality and resigned: "Nixon, a lawyer who had been a member of the House of Representatives, a senator and a vice president, was more accepting of the political order."

But the current occupant of the Oval Office, she pointed out, is an entirely different creature. "Mr. Trump, with no government experience, and little knowledge of how the federal government works, has been a free if malevolent spirit, less likely than even Nixon to observe boundaries," Drew wrote. But Holtzman expressed confidence in an interview that the president would go when impeachment was inevitable. "He's a lot of bravado, but in the end he's a coward and a wimp," she says.

If Nixon's final days are any guide, however, the system is in for a whole lot of shaking before Trump exits. He has already followed Nixon's path in trying to rid himself of his principal nemeses, FBI Director James Comey and Attorney General Jeff Sessions (replaced with a pliant temp, Matthew Whitaker). But he has stopped short of firing special counsel Mueller, as Nixon did with independent Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox, in the infamous "Saturday Night Massacre" of October 1973; that provoked a national uproar and the resignations of Attorney General Elliot Richardson and his deputy, William Ruckelshaus.

Trump could also reach into Nixon's playbook to incite some sort of military or foreign-policy crisis with Iran, China or North Korea to divert attention and rally public support for him as commander in chief. Two days after firing Cox, Nixon rattled Washington (and the world) when U.S. forces were put on Defcon 3—one step short of war—supposedly to deter a Soviet intervention in the Middle East. But with his presidency teetering the following August, concerns grew that Nixon might even deploy military units to Capitol Hill to evict Congress and forestall impeachment.

Nixon's defense secretary James Schlesinger and the Joint Chiefs of Staff were keeping "a close watch to make certain that no orders were given to military units outside the normal chain of command," according to a contemporary account in The Washington Post. "Specifically, there was concern that an order could go to a military unit outside the chain of command for some sort of action against Congress during the time between a House impeachment and a Senate trial."

In the end, nothing came of it, as Nixon accepted the secret promise of a pardon from Vice President Gerald Ford if he would leave office quickly, according to subsequent accounts through the years. But to others, it was a close call. During a meeting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff in December 1973, 10 months into the televised Senate Watergate committee hearings, Nixon "kept on referring to the fact that he may be the last hope, the eastern elite was out to get him. 'This is our...last chance to resist the fascists [of the left],'" recalled one of the chiefs in a 1983 Atlantic Monthly piece by journalist Seymour Hersh. "His words brought me straight up out of my chair. I felt the President, without the words having been said, was trying…to find out whether in a crunch there was support to keep him in power."

Others thought Schlesinger, in particular, had been overcome by a kind of Seven Days in May paranoia. The defense secretary had come "unglued," one of the chiefs said.

Hertling, commanding general of the U.S. Army in Europe before retiring in 2012, also thinks a Nixon coup scenario by Trump is far-fetched. "The military takes an oath to defend the Constitution, not the percentage of people supporting the president," he says. "I don't know of any [general] who would violate the law, the Constitution and their oath to support such an order from the president."

Trump could expect even less sympathy, much less support, from military leaders who have questioned—privately, of course—his fitness for leadership. Departing White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, a retired Marine Corps general, has called Trump "unhinged," according to the Bob Woodward book Fear, which included outgoing Defense Secretary James Mattis, another Marine general, saying the president had the intellect of "a fifth- or sixth-grader." In his final address as national security adviser in April, with Trump in the audience, Army General H.R. McMaster deplored "those who glamorize and apologize in the service of communist, authoritarian and repressive governments."

Forced into a corner, Trump may well—like the dictators he so envies—secretly welcome violent uprisings by his devotees. In addition to his inciting remarks after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, resulted in the death of a counterprotester by a white supremacist ("There are very fine people on both sides"), he blamed the media "for the anger we see today in our society" when an outspoken Trump zealot assaulted a Pittsburgh synagogue killing 11 and wounding six. Even more ominously, he rejected the CIA's report pinning the killing and dismemberment of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi on Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. ("Maybe he did and maybe he didn't!")

"How much further might he go in 2020, when his own name is on the ballot—or sooner than that, if he's facing impeachment by a House under Democratic control?" Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty and National Security Program, wrote in The Atlantic. He could declare another "national emergency," like he did with the Central American caravan in Mexico, she wrote, "a decision that is entirely within his discretion."

Presidents from Abraham Lincoln (who suspended habeas corpus) through Franklin Roosevelt (Japanese-American internment camps) to George W. Bush (warrantless wiretapping, CIA black-site "enhanced interrogation techniques") have regularly asserted or invoked emergency powers. Under legislation passed by Congress during World War II, Goitein wrote, Trump could "activate laws allowing him to shut down many kinds of electronic communications inside the United States or freeze Americans' bank accounts." And, of course, he could deploy troops anywhere, including the Capitol. Tom Ricks, a military affairs journalist, thinks the Pentagon would balk at that. "My bet is that military professionalism runs so deep," he says, "that the Joint Chiefs and other senior leaders would be quick to point out that they can't follow illegal orders."

Likewise, says Holtzman, "some way or another, the system will work. If the evidence is so strong that we have the votes, then he better listen to that."

But back in her day, the Democratic-controlled Congress was careful to win over Republicans before making its final drive to oust Nixon. In January, they'll have a 36-seat majority in the House, while Republicans added two seats to their control of the Senate. And none of the GOP's leaders have broken with Trump, no matter how many misdeeds pile up.

The president has other advantages Nixon lacked. His base is "larger and more cohesive than Nixon's. And Nixon had nothing remotely like the propaganda organ that Mr. Trump has in Fox News," wrote Drew, whose seminal 1975 book, Washington Journal: Reporting Watergate and Richard Nixon's Downfall, remains in print. "The big question," she added in the Times, "is whether there will turn out to be a major difference between the two men when it comes to honoring the decisions of the law, or of the public." The jury's still out on that.