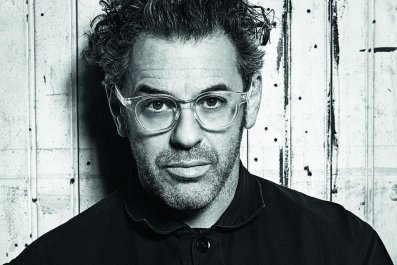

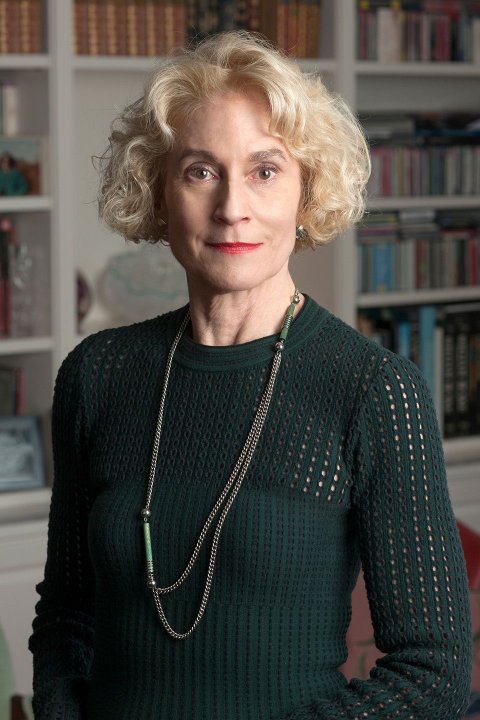

At a glamorous event in December at the New York Public Library in Manhattan, an international who's who—Princess Beatrice of York, model Karlie Kloss, David Rockefeller, Wendi Deng Murdoch and Kerry Kennedy among them—gathered to honor the closest thing philosophy has to a rock star: Martha Nussbaum. The elegant source of their admiration was being celebrated at the third annual Berggruen Prize Gala; the award, which includes a $1 million endowment, is given to "thinkers whose ideas have helped us find direction, wisdom, and improved self-understanding in a world being rapidly transformed by profound social, technological, political, cultural, and economic change."

The 71-year-old Nussbaum, a moral philosopher and law professor at the University of Chicago, is passionately concerned with justice and how it affects the personal and political. But her interest goes beyond the theoretical; she is committed to using philosophy to improve the very vocabulary of public discourse. Nussbaum has written five major books dedicated to this. The most recent, The Monarchy of Fear, is an engaging consideration of our current political crisis from the perspective of emotion—how anger, disgust and envy have been used, since antiquity, to divide people

.

Nussbaum disproves the dig on modern academics—that theylive above the political fray, in ivory towers—perhaps because she takes her cues from the OGs of philosophy. "The great thinkers of the ancient tradition were not detached from political issues," she says. "Seneca was regent of the Roman Emperor Nero, and he was trying to curb him from doing terrible things. There was no escaping political reality."

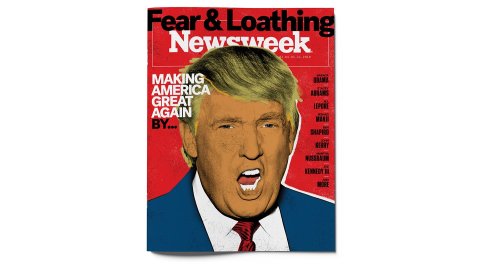

Fear has dominated political conversation in the U.S. for a lot longer than Donald Trump has been president. But the noise of it has grown deafening and debilitating in the past two years. Though Nussbaum is certainly adept at putting fear in context, as well as articulating how it is used for political strategy and to justify rage, she—and we—are equally interested in how to move beyond it. With hate crimes on the rise and talk of impeachment everywhere, there is perhaps no more pressing concern. Below, a conversation on how to "purify" anger and find hope in the Trump era.

In Monarchy of Fear, you write of the epiphany you had on the night Trump was elected president in 2016.

I was in Japan, isolated from my friends and unable to express my upset and fear in the usual way—by talking to and hugging them. There was this churning of panic as the news came in. I already knew the electorate was divided, so why was I so terrified? I realized people were feeling that way all over the place. Some fear can be good, but this was a seething current of emotion preventing people from getting together and talking to each other about what we should do to fix the nation's problems.

How do you define fear?

It is the most primitive emotion, and the first one felt by an infant arriving in this rather painful world, in desperate need of someone to protect them. When we feel helpless later in life, fear makes us scapegoat others. Instead of fixing the problems, we say, "Oh, it's all their fault—those women or immigrants are infesting our country." Rather than useful protest or constructive solutions, we get angry at these handy targets.

Fear is also behind disgust, a visceral reaction to our own mortality and animality—feces and bodily fluids and such. This is true across every single society; we project grossness onto a racial or gender subgroup or caste. A big part of social subordination and discrimination is to ascribe hyper-animality to other groups and use that as an excuse for subordinating them further. And then we feel better about ourselves; we can be the angels, and they can be the animals.

Women, with their menstrual periods and childbirth, have always been targets of this in all cultures. They have come to stand for the disgusting body. There's the long-standing trope of racism, that black people are more animal. And Jews were often compared to insects; Kafka's Metamorphosis was about how a man suddenly turns into a cockroach.

Disgust is something that rears up at times when we feel helpless or fearful. All of a sudden, you find people talking in ways that we thought we had given up. Consider Trump, who talks about African nations as shitholes and immigrants as infestations, like insects.

What is behind the disgust we are seeing toward women today?

Men are angry at women because they aren't doing what they are supposed to do, which is support men. They are in the workplace claiming their own rights and often outdoing men. They are daring to bring charges of sexual assault and harassment. They are just not behaving themselves! And so the desire to beat them down for being disgusting becomes powerful.

But it's a new era. My own senator, Tammy Duckworth, an Iraq War veteran and amputee, wanted to bring her second child to the floor of the Senate. They haven't changed the rules to [explicitly] allow breastfeeding on the floor, but that has happened in other countries. In New Zealand, the prime minister delivered a first child and made a big point of breastfeeding.

There are women all over the country who are doing well, and many, many men who understand this is not "us vs. them" and who have grown up differently, who understand what it is to treat women with respect. There are enough of them that I think the misogynists are a dying breed.

There is a tendency on the left to blame conservatives for spreading the rhetoric of fear.

Fear requires belief that you will be harmed, and it is easily manipulated by rhetoric. But irresponsible rhetoric is not just on the right—it's always happening. And there are plenty of responsible conservatives. [In Monarchy of Fear] I contrast Trump not with some Democrats but with George W. Bush, who, after 9/11, was very careful and responsible in his rhetoric. He said we are going to go get the criminals who did this, but we are not going to demonize an entire religion or people. I don't approve of everything he did, but he was a responsible custodian of public emotion.

Can you give examples of leaders who have been particularly good at that?

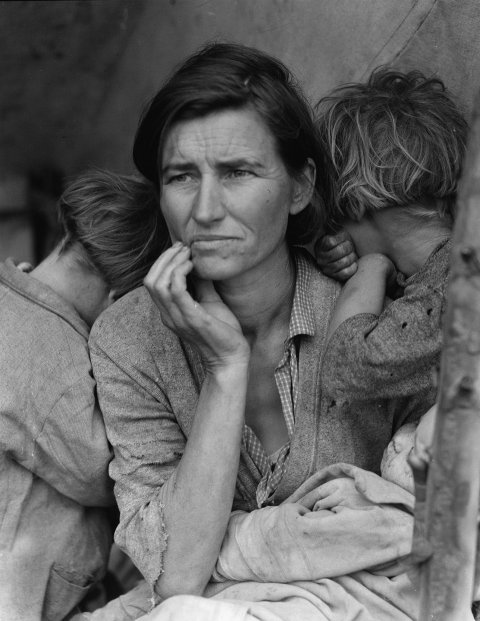

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was an amazingly careful, responsible custodian of public emotion. FDR knew the American tendency was to think that when poor people are suffering, it's their own fault. The attitude of the dominant class was "Oh well, they are lazy slobs who brought the suffering on themselves." He understood that America needed a new emotional attitude towards the poor, and he set out to show that the poor are people of dignity, worthy of respect. They suffer not through bad behavior or laziness but through some cataclysm not of their own making.

He even employed artists to help communicate this, through his New Deal [programs and projects introduced during the Depression]. Dorothea Lange, for example, produced some of the most haunting photographs of American poverty. John Steinbeck was writing in the same vein. This was important.

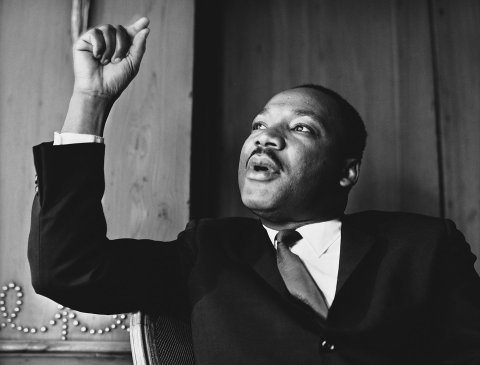

Martin Luther King Jr. is my model for how to think about public anger. His issues as a custodian were quite different; they were about how to shape emotions within his own movement, as well as the general public. What he said is that anger has a protest part, where you say that terrible wrong has been done and we must not have that happen again. But it also has a retributive part, where the intention is to inflict pain on the people who gave us pain. He found that path useless because it's not forward-looking or radical—it is just an easy way of acting out.

He then said, "What do we do when we have these people who come with anger into the movement?" He said their anger has to be purified and channelized and linked with different emotions, such as hope, faith in the possibility of justice and, above all, love. You don't even have to like these people, but you do have to have a basic goodwill toward their humanity and for their capacity for good action. You have to have the sense that it is always possible for people to listen and to change. Turning outward to the white body, he would say, "Well, you left us with a bad check that's come back marked 'insufficient funds,' but you can always pay your debt."

That was a wonderful way of shaping public emotion in the most dangerous and difficult of American political situations. If he had not had that soaring and poetic rhetorical power, the whole country could well have burned down. It's so important that he lived.

You write about the importance of trust to a functioning democracy. Can you elaborate?

If you are in an absolute monarchy, and the monarch is just extracting subservience and obedience, you may be able to rely on what the monarch will do. But reliance is different from trust.

Trust means something more; it means a willingness to be exposed and to allow your project and your future to lie in the hands of someone else. Think about a bad marriage. If somebody is ruling by fear, you might be able to rely on that person's brutal behavior, but you wouldn't trust that person.

A democracy depends on the idea that your hopes and future lie in the hands of people you don't know. Bad decisions will be made, and your opinion won't always win, but there is trust that the outcome—more often than not—will be one we can live with. And that requires a respect for the people on the other side, even when we think they are doing something wrong.

But it's more than respect; trust involves allowing yourself to be vulnerable—to not sealing off the outcome and letting it sit there in the ballot box. It's a big demand that requires a certain attitude towards the political process. I am very distressed at President Trump's attacks on that process. We have lots of evidence that voter fraud is not an issue, but the constant harping on it is a very bad thing. The same goes for Trump's attacks on the media. We need to believe that the news—at least a lot of it—is true, and we need to rely on that for the political process to work.

What about the Christian right and its support for Trump's exclusionary rhetoric?

Religion can be a very powerful source of hope, and some Christian evangelicals have fought back against that sort of rhetoric. Remember when Obama called on the evangelicals for support [during his 2008 presidential campaign]? He got pushback for that, but it was the right thing to do. You don't want to close out one segment of the public. You do want to say that there is no place for hateful rhetoric in America.

How is hope an antidote to fear?

Usually, hope is considered the opposite of fear, and in a way it is. But what the philosophical tradition points out is that the two are very similar: Both require that the outcome, which is highly uncertain, is going to be something meaningful and important to you.

The Stoics [followers of a Hellenistic philosophy founded in the third century B.C.] taught learning not to care about uncertain things, about pulling all your cares inside yourself. If you were a complete stoic—caring only for your own reason and will—then you would not have fear or hope. That was a natural response in the world at the time because so much was rapidly turning into tyranny. But it was still a bad response. If you think, as I do, that it's important to love other people or your country or things outside your control, then you are going to have both fear and hope.

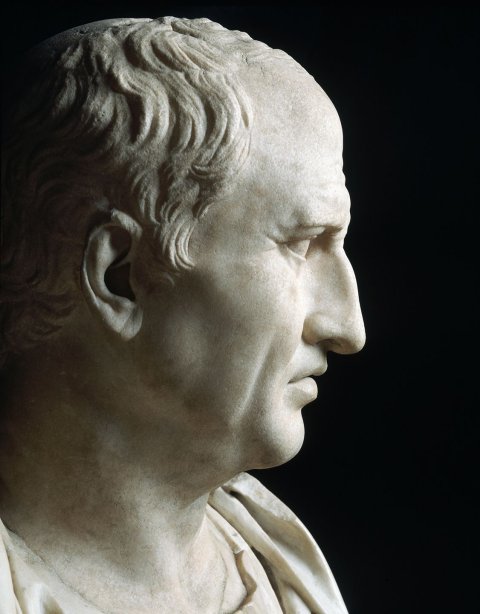

Cicero was a Stoic who loved the Roman Republic—he fought to the death for it. At one point, he was mourning the death of his daughter and of the republic. His friends told him he should stop and be a proper Stoic, and he said, "No, these are important things, and I should grieve." That's how I think we should follow his example—hopefully without getting murdered by political assassins! He stuck his neck out, quite literally, for the assassins' stroke.

But hope is not a matter of probabilities, right?

True. You could have a relative ill in the hospital, and the probability of a positive outcome is not very good, but you could still have hope. On the other side, the probabilities might be very good, but you could still have fear and have crippling anxiety.

But hope is also not just an emotion; it's a syndrome linked to action. An important young female philosopher, Adrienne Martin, wrote a very good book on this: How We Hope: A Moral Psychology. She points out that hope is a way of looking at a situation with a disposition to act. If you are fearful, the action tendency is to run away and hide your head. But hope is: I will get in there and try to make this good outcome more likely.

Hope energizes us. It gets us to run for office or support candidates. We won't do that if we sit back in fear and despair. It is something you can produce in yourself with habits of mind and heart that make it more likely that you will have that hope rather than fear syndrome.

What are some practical habits of hope?

Everyone has to find their own way. It could be participating in politics or joining a protest movement or practicing religion. Certainly, in Chicago, where I live, black churches are a center of hope for the community. My synagogue is social justice–oriented—the idea being that each person can do something for the community; we have gardens and produce fresh produce for the poor.

A big constant is the arts, which are tremendous schools of hope. Whatever the work is, even if it's really grim, artists get us to examine the insides of people in a way that isn't filled with disgust, that leads us to a deeper understanding.

I'm about to teach a course on Arthur Miller's play Death of a Salesman. It's a terrifying play about America and the destruction of the American dream, but it opens up something in our own community and in people that we might not have understood. Artists have a vision of humans as capacious; they don't view people as tools, and that attitude promotes habits of hope.

But so does philosophy. The liberal arts education is such a great school of citizenship because it has the imaginative part, as well as the Socratic part. Socratic philosophy gets you to a model of rational, respectful debate. If you're in a philosophy class, you're not going to be yelling at somebody; you're going to be dissecting their argument and trying to figure out what the premises are, whether the premises lead to the conclusion and, if not, what went wrong. You get into the habit of rational, respectful deliberations, and that is an important practice of hope.

You talk of rational debate. How do we get back to that?

I am currently developing a new course, Conflicting Theories of Justice and Law, for students who are polarized. I want to give them a safe space to argue together. They'll be presented with conservative, libertarian, liberal and more radical theories, and then they can ask themselves where they fit into the debate. That is one of the most hopeful things of all—a classroom where people who differ greatly can talk with friendship and civility across tremendous divides.

I will be co-teaching it with conservative colleagues, and that's important because it might get students to choose a course they wouldn't think of taking. They often vote with their feet, and they polarize themselves. Our law school is unique among the major law schools because we have the largest proportion of very conservative religious students. If you are Mormon or evangelical Christian, you will not be marginalized or vilified the way you might be at Harvard or Yale.

Any last thoughts on overcoming cynicism or apathy during these difficult times?

I think we should honor people, like Cicero, who take risks, who are willing to get involved and who are not overly self-protective. Politics is difficult and painful, and the people who get in there and do it with good grace and joy—it's one of the most important things anyone can do.

To me, the cynical response is totally unappealing. The ancient Cynics are very different from what's meant by cynicism today, which is thinking everything is worthless. If you think, as I do, that this is the only life you've got—well, if that's not worthwhile, what is? The world has so much in it that is wonderful and beautiful—people, nature, animals. I hope that young people, in particular, do what they can to preserve the planet. It needs a lot of work if we're going to hang on.

You can find Martha Nussbaum's Monarchy of Fear here.