There are roughly 120,000 people waiting for organ transplants in the United States. On average, 79 patients across the country get the transplant they need each day, while 22 die waiting because of a shortage of donated organs.

Part of the reason for that shortfall is that not all donated organs can be used. For example, only about a third of 82,053 potential donor hearts were accepted for transplant between 1995 and 2010, a study from the Stanford University School of Medicine found last year. One factor is the standard method of transport. Cold storage offers a very short window of time to get the organ from donor to recipient—typically less than four hours for a heart, six for lungs and slightly longer for others.

"Since the dawn of organ transplantation until today, every aspect of organ transplant therapy has seen advancement...except one area: organ preservation for transplant," says Dr. Waleed Hassanein, president and CEO of TransMedics Inc., a medical device company he founded in 1998. Hassanein, who completed a surgery residency and a cardiac surgery research fellowship, developed the Organ Care System to change that.

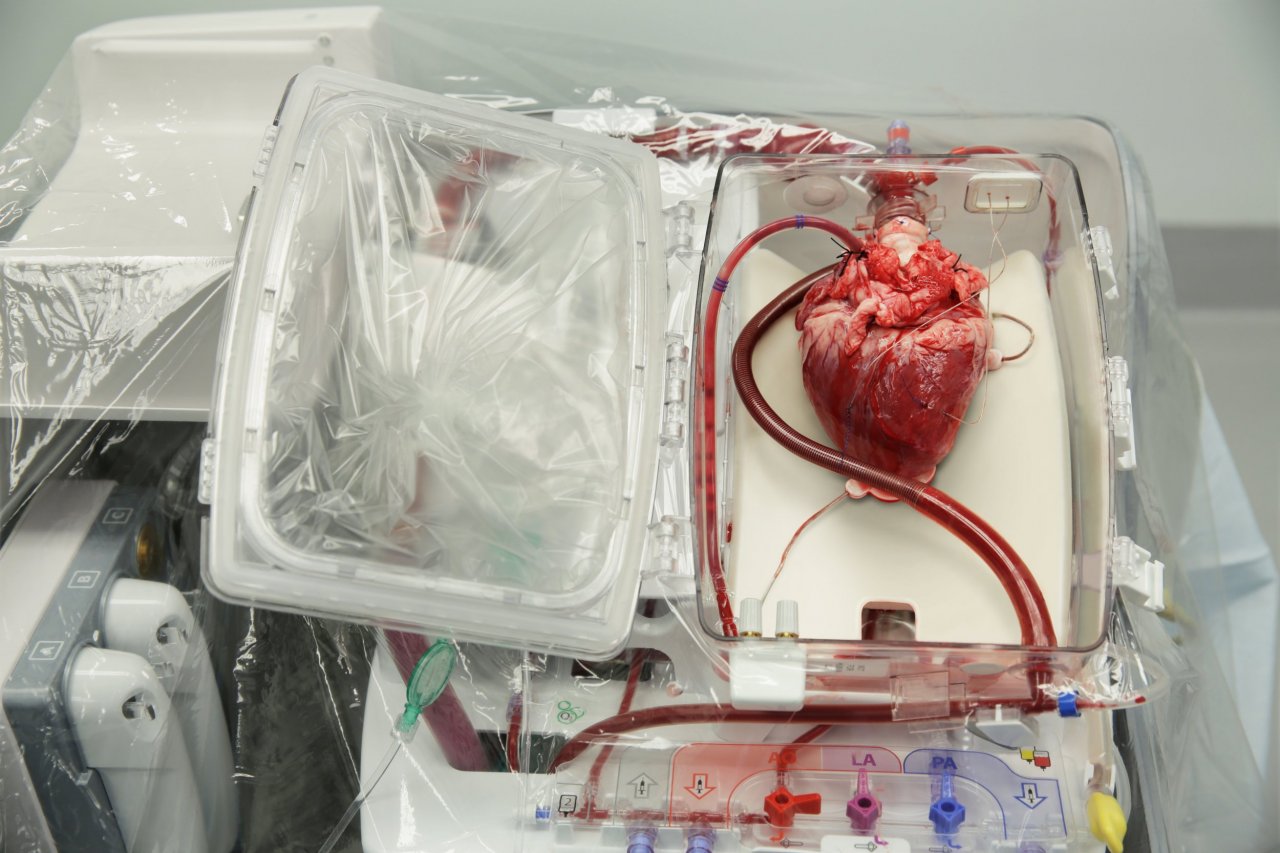

Storing an organ on ice causes injury to it over time. "The longer an organ spends in that environment, the worse it becomes," Hassanein says. The OCS—used thus far for heart, lungs and liver—flips cold, static storage on its head. Instead of chilling an organ and racing against the clock as it begins to decay, the system keeps it warm (roughly at body temperature), perfused with oxygenated blood and functioning as it would inside the body. In other words, a heart beats, lungs expand and contract with air, and a liver creates bile en route to transplant. Theoretically, there is no limit to how long an organ could spend in the OCS.

The compact portable console has a universal power system, a battery, a pump, a wireless monitor, embedded software and an organ-specific perfusion module, which is a sterile single-use cassette with sensors to monitor the organ it holds.

The OCS is already in commercial use in Europe, Canada, Australia and parts of Asia, but TransMedics is still securing Food and Drug Administration approval in the U.S., with three clinical trials underway. The company is also working on versions for the kidney and small bowel.

More than 700 transplants all over the world have used the OCS in the past decade, including a recent heart transplant for Marv Vandermolen at Spectrum Health's Meijer Heart Center in Grand Rapids. By the time the Michigan native retired early, at 55, meetings on the other side of the building had become daunting. "Just walking from where I was at to other end would wipe me out," he tells Newsweek. "I would be sweating and tired and short of breath."

Having worked as a mechanical technician in research and development, he was open to participating in the OCS Expand Heart clinical trial. Like the OCS Expand Lung trial, it focuses on organs that would otherwise go unused. Vandermolen, now 63, knew it meant he might get a new heart sooner. Four months after his transplant, he's back to working on old cars, grocery shopping and going on day trips to Lake Michigan.

The ultimate goal is "to make more and better organs available for patients," says Hassanein, who hopes to increase the percentage of organs accepted and the number of transplants performed. "We expect OCS to be next standard of care," he adds, imagining a time in the near future when "every organ transplanted will be perfused in one of our systems."

"We believe it's a 'when' not 'if,'" he says.