Last November, when James Mattis traveled to Bedminster, New Jersey, at the behest of the president-elect, his close friends were shocked. They couldn't believe Mattis, a retired Marine Corps general, would consider working in the new administration as secretary of defense. "Jim," his friend Peter Robinson asked him, "Donald Trump?"

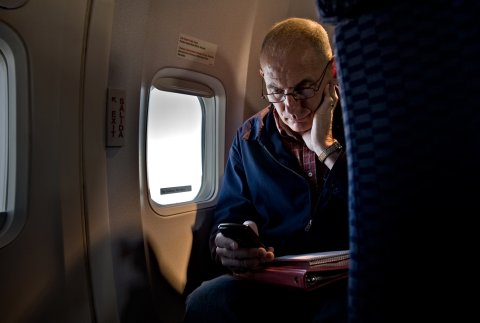

For three years after leaving the Marines, Mattis had been ensconced at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, padding around campus in sneakers and jeans, a backpack slung over his shoulder, happily working on a book. The man retired Marine Colonel Gary Anderson calls "the finest combat leader our military has produced in decades'' looked like an "old graduate student," as Stanford colleague Robinson puts it. And he had little intention of changing that. Until Trump called.

Two other prominent retired generals received similar calls—and they, too, agreed to serve: national security adviser H.R. McMaster and newly appointed chief of staff John Kelly, who first joined the administration as the head of Homeland Security.

Trump calls them "my generals," a title their colleagues say makes them a bit uncomfortable. And now, six months into a chaotic administration, under an unpredictable president who many fear isn't fit for the job, the skepticism that many of their friends initially evinced has been replaced by something else: "relief," says Johns Hopkins military historian Eliot Cohen, a friend of all three. "These are grown-ups in grown-up jobs. God knows this administration needs them."

It is hard to overstate how widespread that feeling is among key U.S. allies—and even some adversaries, especially now with a mounting nuclear crisis in North Korea and Trump's use of bellicose rhetoric unnerving friends and foes. One Chinese diplomat who, like many others in this story, would speak to Newsweek only on condition of anonymity, says his government—like many others—had "no idea" what to make of Trump when he won the presidency. But it was "somewhat reassured" by the appointments of Mattis, McMaster and Kelly, all of whom had "reputations as intelligent, reasonable men," the diplomat says. The ambassador of a key U.S. ally who's in almost constant communication with the administration about the crisis in North Korea is more blunt. "It's hard to imagine what things would be like without them."

All U.S. military officers serve at the pleasure of the president. The same holds true for Mattis, McMaster and Kelly—so at any time, Trump could tell them their services are no longer required, and each would take his leave. But in this White House, the relationship between the president and "his" generals may be more nuanced. The president has no prior experience in politics or national security. Combine that with the widespread respect all three generals bring with them, not to mention their reputations for seriousness and intelligence, and it means they possess something that Donald Trump the dealmaker understands well: leverage—leverage over him.

The incompetence of this administration—from the initial botched "travel ban" (which Kelly as Homeland Security director wasn't even briefed on before the White House rolled it out) to its failure to date to push through any significant legislation—is striking. But "that stuff would look like small, small potatoes if any of the generals in Trump's orbit" were to bail, says one former Obama administration Cabinet member who knows each of the men. "It would be a mortal wound," says this source. "If any of these guys quits for something other than legitimate personal reasons—an illness or some such—it's going to be really bad news." The reason: It could mean "that the crazies really are in charge," he adds, referring to Trump's chief strategist Steve Bannon and his loyalists.

Today, few are obsessing about Seven Days in May scenarios (the famous Cold War–era film in which a hawkish general plots a coup against a peace-seeking president). Instead, establishment Washington and America's friends around the world, as Cohen jokes, are now paraphrasing Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men: "We want those guys on that wall; we need those guys on that wall." That is especially true now, as the administration tries to prevent a disaster in North Korea, where the regime continues its march toward fielding a nuclear weapon it can fit onto an intercontinental missile. As Pyongyang snarls—threatening to fire missiles near Guam—and Trump responds in kind, one East Asian diplomat in Washington praises Mattis and McMaster, as well as Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, for "their calming presence." "They don't get rattled, and their rhetoric—both in public and in private—is precise and matter of fact."

Mattis, McMaster and their staffs spent early August methodically working through possible military responses to North Korea—including, Newsweek has learned, a possible cyberattack that could disable Pyongyang's missiles. At the same time, several sources say they're stressing to Trump the catastrophic risks of a pre-emptive strike. None of them will say whether a past Pentagon estimate of potential casualties in a new Korean war—1 million dead—still holds. "It's impossible to predict [how many casualties] there'd be," McMaster says. "War is unpredictable. You just have to assess the risks and figure out how to mitigate them."

Trump, his generals believe, seems to understand those risks. Though his rhetoric may be "hot" on occasion, as one National Security Council (NSC) staffer says, "the decision-making on this is not going to be impulsive. It's going to be very, very deliberate."

Bush's War, Obama's Mess

Well before Mattis, McMaster and Kelly, retired generals had long wielded power in the White House—from George C. Marshall in the 1950s to Colin Powell at the turn of the century. Never, however, has there been a triumvirate of ex-military men with such clout advising the president. Each has a stellar reputation as a warrior and as a scholar. In 2004, Cohen says he visited Mattis in Iraq and brought him a "particularly well-reviewed copy of the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius." The general accepted the gift and then "spent the next 15 minutes comparing that version to the two other versions...that he owns, one of which he had with him in Ramadi."

Mattis got a master's degree in international security from the National War College, but, as his friend Cohen puts it, "he's someone who has never stopped learning—ever." His personal library reached some 7,000 volumes before he gave much of it away, and he often gave his Marines reading lists before deployments.

McMaster is the author of Dereliction of Duty, a meticulously researched and withering account of how badly flawed U.S. military decision-making was in Vietnam during Lyndon Johnson's administration. The book came out of his doctoral thesis at the University of North Carolina, and McMaster says its core lesson—getting the best information to the president at all times, whether he wants to hear it or not—informs his work as national security adviser "practically every day."

Kelly got a master's in national security studies from Georgetown University and later, as a lieutenant colonel, spent two years studying at the National War College in Washington, D.C.—something only elite armed service members are chosen to do.

What bonds Trump's generals and informs the way they see the world is their shared experience in Iraq. Kelly served as Mattis's assistant division commander there and saw how coldly decisive his superior officer could be. During the initial push toward Baghdad, Kelly had been struggling to get a regiment commander to quickly take the town of Nasiriyah. He asked the commander to visit Mattis, who, after hearing why he was hesitating (he said he was tired, among other things), promptly relieved him of command. Nasiriyah fell, and soon Baghdad did too. Mattis then sent his tanks and artillery home and visited Iraqi military leaders in the area. "I come in peace," he told them. "I didn't bring artillery. But I'm pleading with you, with tears in my eyes: If you fuck with me, I'll kill you all."

Mattis and Kelly both came from working-class families and enlisted in the Marines during the Vietnam War. As a young man growing up in Pullman, Washington, Mattis says he took some time to get his act together, and he credits the Marines with helping him focus. Well into his career, he recalls coming home to his parents' house and reading a newspaper in their living room. His mother, who was sitting with him, began to laugh. "What's so funny?" Mattis asked. "Oh Jim," she responded, "I'm just darn glad you didn't end up in jail."

McMaster focused on a military career early on. He attended the elite Valley Forge Military Academy for high school and then went to West Point. As a commander in 1991 during the first Gulf War, his unit of nine tanks destroyed 28 Iraqi tanks in 23 minutes, without suffering a loss. The Battle of 73 Easting, as it's known, is now taught at West Point. Fifteen years later, McMaster ran a highly effective counterinsurgency in the Iraqi town of Tal Afar—one that became a model for General David Petraeus's "surge" later in the war.

Kelly culminated his career in the Marines as head of Southern Command, running all U.S. forces south of the border. In this role, he became sensitive to the security risks posed by widespread illegal immigration—an issue that obviously appealed to Trump—and he has thinly disguised contempt for politicians who favor open borders and sanctuary cities.

His career is notable in one other respect as well: He was the senior-most figure in the U.S. military to lose a son in combat in either Iraq or Afghanistan. Robert Kelly, then a 29-year-old Marine officer, stepped on a land mine in Sangin, Afghanistan in 2010 and died instantly. In 2014, his father addressed a meeting of Gold Star parents in California. He spoke of the heroism of two Marines killed in Iraq protecting a police station from a truck bomb. It was a deeply moving ode to the Marines' warrior ethos, made all the more powerful because the man who delivered it, like those he addressed, was also Gold Star parent.

Of the three generals, Mattis is the senior figure, so when he resigned as chief of Central Command in 2013—he had succeeded Petraeus in that role, which oversees the U.S. military in the Middle East—the move reverberated throughout the armed forces. Many saw it as vote of no confidence in the Obama administration. Mattis had grown increasingly frustrated with the White House because he felt it had caved to Iran on a dangerous nuclear deal. After leaving the Marines, he became a quiet critic of the administration's foreign policy—and then a more vocal one. He gave a brutally frank account of President Barack Obama's foreign policy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., in 2014. "The president and his [foreign policy advisers] have a remarkable ability to absolve themselves of responsibility for anything," he said of the rise of the Islamic State group (ISIS) that followed in the wake of deteriorating conditions in Syria, Iraq and Libya.

And while Obama's defenders bristle whenever Trump says he inherited "a mess" abroad, he was hardly first to make that claim; Mattis had done so long before him.

'He's Not Going to Do Anything Crazy'

It surprises many people that Mattis is now a central figure trying to sort out that mess. While he was never a Never Trumper, Mattis did, as a matter of courtesy, entertain an entreaty from conservative pundit Bill Kristol to jump into the 2016 Republican primary as it became clear Trump was gaining traction. He demurred, but when he met with the president-elect in Bedminster, says a Mattis friend, the general told Trump, "I had some problems with some of the things you said during the campaign." Trump waved away his concern. "That's OK. Don't worry about it."

At the Pentagon, Trump has allowed Mattis to gain more and more authority. Early on, he drove the administration's reset of Middle East policy. He backed bombing a Syrian airfield after Bashar al-Assad's regime again used chemical weapons on its own citizens, and then—along with McMaster at the NSC—he helped bolster the White House's relationship with America's traditional allies in the Middle East: Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf Arab states. All were critical of Obama's handling of the war in Syria and the nuclear deal with Iran. Trump is also allowing Mattis to set troop levels in Afghanistan—in contrast to the micromanaging of the previous administration. When not focused on North Korea, he and McMaster are now deeply involved in reviewing the U.S. overall strategy in Afghanistan.

From his perch at the Pentagon, Mattis has largely avoided clashing with the White House. But he still gets sideswiped by the impulsive president. When Trump tweeted his enthusiasm for a Saudi economic embargo of Qatar because it allegedly funds groups the U.S. considers terrorists, Mattis quietly let Trump know that the Al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar is critical to U.S. operations in the region and would be badly hindered by the Saudi embargo. That was the end of the administration's enthusiasm for isolating the Qataris.

Mattis was similarly taken aback when Trump said the U.S. military would no longer accept transgender volunteers. The former Marine general had accepted the Obama administration's position on the matter. And though Trump claimed he had consulted with "my generals" before making the decision, Mattis made it clear he hadn't. The Pentagon, his spokesman said, would await formal instructions from the commander in chief, rather than act on his tweet. (Aides say Mattis would follow orders on this issue if Trump insists, but privately may push back.)

McMaster has not been as fortunate as Mattis in avoiding the White House's internecine squabbles. In early August, he was forced to fight off an effort to undercut his authority by Bannon, who supporters say is protecting the president's campaign promises: On economics, he's a protectionist (which McMaster sees as a stance that poses problems with key allies), and on foreign policy, he's a nationalist who is deeply skeptical of America's involvement in a place like Afghanistan. (In McMaster's, Mattis's and Kelly's view, abandoning the country risks a return of the alliance between the Taliban and Al-Qaeda that led to the September 11 attacks.)

Bannon's minions at Breitbart News and other sites catering to the "alt-right" white nationalist movement began accusing McMaster of undermining the very policies that got Trump elected: avoiding messy, unending foreign wars, getting tough on trade partners and getting out of the Iran deal. The Iran smear of McMaster is particularly specious: Bannonites say he favors staying in the deal, allegedly a sign that he's pro-Iran. But McMaster echoes Trump in saying "that in many ways the nuclear deal with Tehran was the worst deal ever," and he makes it a point to say that Iran's influence in the Middle East is "malign and destabilizing." In three months, the administration must decide whether to yet again certify Iran's compliance with the deal. McMaster is acutely aware that key allies in Europe do not want the U.S. to pull out of the agreement, and that if the president does, it will take a lot of diplomatic hand-holding among those allies. "Von Clausewitz," says a friend of McMaster's, referring sarcastically to Bannon, "is apparently unaware of that."

This contretemps may not last long. The combination of Kelly's appointment as chief of staff and the increasing urgency of the North Korean nuclear program are cementing the generals' authority. That was plainly on display in late July, when Kelly insisted that Anthony Scaramucci, the newly appointed communications director, be fired after an obscenity- laden rant to a reporter. "Kelly viewed him as someone who was unqualified for the job and who had embarrassed the president and the presidency," says a White House source. His message to Trump was straightforward: "Look, this is the kind of stuff that has to end. I'm going to run things my way, or I'm not taking the job." Trump agreed, and the "Mooch,'' his erstwhile New York City buddy, was escorted from the White House.

Kelly also told the president that McMaster and Mattis had to be allowed to make their own hiring and firing decisions. The next day, McMaster was finally able to get rid of four staffers loyal to Bannon who had previously been protected by Trump. Among them: the senior director of intelligence at the NSC, 31-year-old Ezra Cohen-Watnick, whom colleagues at the other intelligence agencies viewed with barely concealed contempt, in part due to his inexperience. "The day John Kelly became chief of staff," says one official, "was not a good day for Steve Bannon and was absolutely a good day for General McMaster."

As if to emphasize the point, Trump issued a statement aimed at getting Bannon and the alt-right to call off the attack. "General McMaster and I are working very well together," the president said. "I am grateful for the work he continues to do serving our country."

There are good days in Trumpland for the three generals, but there are still not so good days. After North Korea condemned U.N. sanctions imposed on August 5, saying the United States "would pay dearly," and then threatened more nuclear and missile tests, Trump exploded. On August 8, he said that if North Korea continued to threaten the U.S., it would be met with "fire and fury." Such over-the-top rhetoric stunned everyone—including McMaster, Mattis and Kelly, who was with Trump in Bedminster at the time. None had any idea a statement like that was coming, according to several White House aides. McMaster and Mattis, along with Tillerson, tried to assuage nervous allies that, no, war was not imminent, and that they were still committed diplomacy, even if Pyongyang says it's not.

"We know by now there's going to be some outbursts from this president," says a person close to McMaster. "The good news is, he does really listen to these guys, almost all of the time. And that means he may say some crazy stuff, but he's not going to do anything crazy."

Asked if he thinks Trump will always listen to "his" generals when he needs to the most, however, the source just shrugs.

"Your guess is as good as mine."