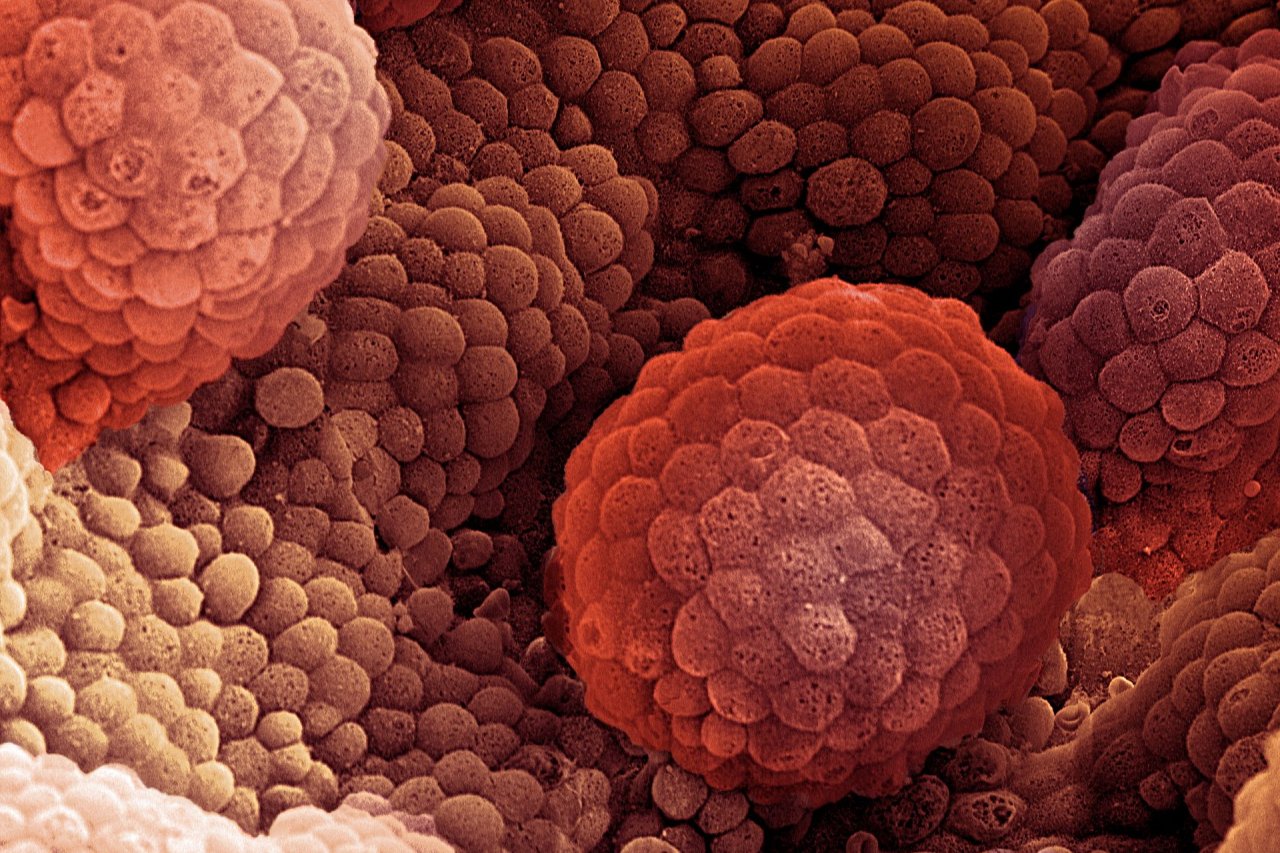

For most patients diagnosed with prostate cancer, the course of action is clear. Some tumors require no immediate treatment. Others can be removed with surgery or radiation. And some require a more aggressive attack.

However, for an estimated 30 percent of patients—about 54,000 men in the U.S. every year—the disease is more erratic. Their so-called intermediate-risk tumors could grow slowly or quickly, or may have already sent undetected malignant cells around the body. Diagnostic tests cannot accurately predict which of these tumors will prove harmless or deadly, often leading to excessive or insufficient treatment.

But a new study has uncovered a particular genetic signature that indicates the one-third of intermediate-risk prostate cancers bound to be problematic. A particular combination of genetic attributes renders these tumors more likely to recur or resist treatment and, as a consequence, become life-threatening. With this signature in hand, identifying patients who need rigorous treatment up front—as well as those who do not—is now within reach.

Related: Researchers are close to blocking one of the deadliest cancer genes

Researchers at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, which is affiliated with the University of Toronto, and several Canadian universities obtained genome sequences of 477 prostate cancer patients. All patients had been diagnosed with localized disease—that is, their tumors were confined to the prostate—and were treated with either surgery or radiation. Using this database, the researchers zeroed in on five genetic characteristics of patients with a large increase in prostate-specific antigen, an indicator of recurrence within two years of treatment. "These are the ones who have lethal disease," says study co-author Robert Bristow of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. "We missed the boat by not giving them medication that would travel throughout the body." In the U.S., this group accounts for about 4,000 patients per year.

This genetic portrait could guide therapy. "It provides a path for testing whether or not an individual tumor is destined to be aggressive," says Mark Pomerantz, an oncologist at Boston's Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, "and that may influence our upfront treatment decisions."

The study, published in Nature this month, included 200 whole-genome sequences, which decode the entire span of an individual's DNA rather than just the small portion that encodes proteins. This broad view enabled researchers to spot variations in genes that contribute to the spread and proliferation of cancer cells, an inadequate immune response and faulty DNA repair.

The researchers are developing a routine test for the signature and starting a clinical trial to study whether more aggressive treatment benefits patients with this genetic fingerprint. "We are in full throttle," says Bristow.